Transgender Identities & Spiritual Traditions

in Asia & the Pacific: Lessons for LGBT/Queer APIs

by Pauline Park

presentation at the Pacific School of Religion Chapel

Berkeley

2 April 2013

I’d like to begin by thanking Jess Delegencia of the API Roundtable for inviting me to speak here at the Pacific School of Religion; I am honored by the invitation and delighted to have the opportunity to speak at such a distinguished institution. And this chapel seems an especially appropriate setting to be discussing about the relationship between transgender identity and spirituality. I would like to focus specifically on the question of the relationship between transgender identity and religious and spiritual traditions in pre-modern Asian and Pacific Islander societies.

There is a very wide misconception that ‘lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender’ (LGBT) constitutes a purely modern phenomenon created by late nineteenth and early twentieth century sexologists and activists. In fact, every pre-modern Asian and Pacific Islander society had what could be termed ‘proto-transgenderal’ and homoerotic traditions which anticipate these contemporary LGBT identities, even if there are significant differences between the pre-modern and the contemporary identity formations.

I would like to suggest that it is important for us as LGBT/queer APIs to address the biggest misconception in API communities — namely, that we are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgendered because we’ve been hanging around white people too much. The implicit assumption behind that misconception is one of a viral model of gender identity and sexual orientation. The slogan of Queer Nation was “We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it.” When it comes to homosexuality and transgender, the truth is that we have been here — in every Asian or Pacific Island society — since time immemorial.

And third, I would like to address the misconception that transgender identity is at odds with religion and spirituality and that gender variance is and can only be an expression of the profane.

To begin with, while it is true that contemporary LGBT identities are of recent vintage, it is equally true that there were people in every pre-modern Asian or Pacific Islander society who were like us in important respects and whom we would call lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgendered. The last are what I would call ‘proto-transgenderal’ — a term I coined to describe those whom we might consider transgendered in centuries long before the term ‘transgender’ came into common usage.

China has homoerotic and proto-transgenderal traditions going back centuries. The ‘passion of the cut sleeve‘ (duànxiù 断袖) — the love of the Han dynasty Emperor Ai (27 BC-1 AD) — for his male favorite, Dong Xian — is the source of the Chinese euphemism for homosexuality (‘cut sleeve’). The other popular Chinese euphemism for homosexuality – the ‘half-eaten peach‘ (yútáo 余桃) – goes back even further, to the Zhou dynasty Duke Ling of Wei (衛靈公) (534-403 BC) and his male lover, Mixi Zia(彌子瑕). Ever since Mizi Xia and Dong Xian (董賢), the half-eaten peach and the cut sleeve — yútáo duànxiù (余桃断袖) — have been euphemisms for male homosexuality in China. As in many societies, homosexuality and transgender were not always distinct and were often conflated, so that examining the one requires examining the other, and vice-versa. Relations between males in ancient China and other pre-modern Asian and Pacific Islander societies were often highly gendered, with the younger partner often the more feminine in gender expression, even if he did not necessarily ‘present’ as a woman.

But in theater, women’s roles were in fact usually played by the younger male actors in the company. So, for example, there is the tradition of the Beijing opera dan, as dramatized in “Farewell My Concubine,” the 1993 film by Chen Kaige starring Leslie Cheung as the male actor and singer who plays women’s roles on stage. And of course there is the Japanese tradition of kabuki, though the onnagata — the male who plays women’s roles in the kabuki theater — at least in contemporary Japan is not necessarily gay or transgendered.

There is also an interesting connection between religious and spiritual traditions and lesbianism and bisexuality in traditional China. For example, the Golden Orchid Association was a Chinese women’s organization that celebrated ‘passionate friendships’ and embraced same-sex intimacy. The origins of the Jin Lan Qi (Jinglanhui) have been traced as far back as the Qing dynasty. Members of the group participated in ceremonies of same-sex unions, complete with wedding feasts and exchange of ritual gifts (see Cassell’s Encyclopedia of Queer Myth, Symbol & Spirit, 1997, p. 161). Women of the Golden Orchid Association engaged in sexual practices described as ‘grinding tofu.’

The ‘Rubbing Mirror Society’ was founded in Guandong province in the seventeenth century by a Buddhist nun and its members participated in same-sex unions (see Cassell’s Encyclopedia of Queer Myth, Symbol & Spirit, 1997, p. 237). Originally known as the ‘Ten Sisters’ by the nineteenth century, the society was called the Mojing Dang. The interesting question — for which one finds little if any documentation — is whether such female relationships were as highly gendered as male homoerotic relationships so often were in ancient China, with one member of the pair playing the ‘butch’ role and the other the ‘fem.’

In the mid-nineteenth century, the philosophy of Chai T’ang (Jaitang) became popular (see Cassell’s Encyclopedia of Queer Myth, Symbol & Spirit, 1997, p. 108). Emerging out of a syncretic Taoist/Buddhist milieu, the philosophy of Chai T’ang found expressing in communal living in ‘vegetarian halls’ or ‘spinsters’ houses’ which emphasized gender equality among members who revered Guanyin (Kwan Yin), a Buddhist bodhisattva of compassion.

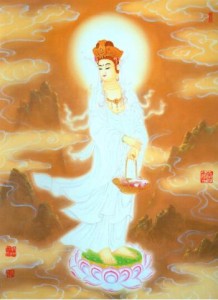

Guanyin, the bodhisattva of compassion

Called the ‘goddess of mercy,’ Guanyin — “She who hears the cries of the world” — is sometimes portrayed as Avalokiteshvara, the male Buddha of the Pure Land who transforms into a female one (Vern L. Bullough, cited in Cassell’s Encyclopedia of Queer Myth, Symbol & Spirit, 1997).

Guanyin statue in a Chinese temple in Thailand

Revered by Chinese Buddhists and Daoists alike, Guanyin has a special place in the hearts of transgendered Chinese and Asians who know of the transgenderal version of the story of the deity of compassion.

In Tibet, the Gelug (or ‘Gelugpa’ – ’Yellow Hat’) strain of Buddhism has long been associated with same-sex relations between monks in its monasteries, especially in the Gelug monastery at Sera (see Cassell’s Encyclopedia of Queer Myth, Symbol & Spirit, 1997, p. 10).

There is a long tradition of homosexuality in Japan, prominently featuring Buddhist monks (see Gary Leupp, ”Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan,” University of California, 1997). “The Great Mirror of Male Love” (Nanshoku Okagami), is a collection of 40 homoerotic stories from 1687 by Ihara Saikaku (1642-93) that depicts the nanshoku tradition of male love in all its variety, including some involving monks in Buddhist monasteries.

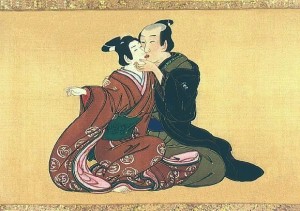

A samurai kisses a kabuki actor in a shunga hand scroll

(Miyagawa Issho, c. 1750).

Korea has at least four distinct traditions that anticipate contemporary LGBT identities. First, there is the hwarang warrior elite — sometimes referred to as the ‘flower boys of Silla’ (the dynasty that united the Korean peninsula in the seventh century) — an elite corps of archers who dressed in long flowing gowns and wore make-up. Second, there are the namsadang, the troupes of actors who went from village to village. Among the namsadang, the youths played women’s roles, as in Elizabethan theater. It is said that the youths were often lovers of the older men in the corps. Third, there is the tradition of ‘boy-wives,’ in which youths would wed older men and be recognizes as wives of the men.

And finally, there is the the paksu mudang — the male shaman who performed what was a woman’s role in the ancient shamanic spiritual tradition that Koreans brought into the Korean peninsula from eastern Siberia in pre-historic times.

Korean mudang

The mudang was the priest-like figure in Altaic shamanism. In that culture — the oldest level of Korean society, which predates the introduction of Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism into the peninula by the Chinese — the mudang was always a woman, but not necessarily female. A significant number of mudang were male, and some of these paksu mudang (male mudang) may have lived as women as well as performing the sacred rites and rituals of the mudang spiritual tradition, though there is not enough documentary evidence to come to any definite conclusions as to whether many or most them lived as women and were recognized as such outside the context of the sacred rites and rituals tnat they performed.

Korean mudang

In South Asia and Southeast Asia, there are many examples of homoerotic and proto-transgenderal traditions, including that of the hijra of India, the eunuchs who undergo ritual castration in order to serve as temple priestesses in a tradition that has survived in India to the present day. The lives of the hijra are documented in “Harsh Beauty,” a 2005 film by Alessandra Zeka. The hijra undergo ritual castration and devote themselves to the hindu goddess Bahucharamata, living in group houses known as jemadh, as described in Serena Nanda’s classic work, “Neither Man Nor Woman: The Hijras of India” (1990).

a hijra in the film “Harsh Beauty”

Vietnam also has a shamanic tradition, known as dao mau, also presided over by shamans, many of whom are transgendered. The filmmaker Nguyen Trinh documented this tradition in “Love Man Love Woman,” his 2007 documentary about Master Luu Ngoc Duc, one of the most prominent spirit mediums in Hanoi. In the dao mau tradition, it is usually feminine males (referred to as ‘dong co’) such as Master Luu Ngoc Duc who preside over the country’s popular mother goddess religion.

Master Luu Ngoc Doc

Master Luu Ngoc Duc is but one of many examples of proto-transgenderal shamanic traditions that have survived into the twenty-first century. Another such tradition is that of the bissu, documented in the 2005 film, “The Last Bissu: Sacred Transvestites of South Sulawesi, Indonesia” by Rhoda Grauer.

Sulawesi bissu

The Long Island University professor’s documentary focuses on Puang Matoa Saidi, a contemporary bissu priest who is attempting to keep the bissu tradition alive.

In Thailand, there are the kathooey (often translated as ‘ladyboys’) of Thailand (see, for example, Michael G. Peletz, ”Transgenderism and Gender Pluralism in Southeast Asia since Early Modern Times,” in Current Anthropology, Volume 47, Number 2, April 2006,) though I have not come across any evidence that they traditionally played a shamanic role in Thai Buddhism or any other spiritual tradition indigenous to Thai culture.

The Pacific Islands have many homoerotic and proto-transgenderal traditions, including those of themahu in Hawai’i, the fa’afafine in Samoa (see “The Transgender Taboo“), the fakaleiti in Tonga, thevaka sa lewa lewa in Fiji, the rae rae in Tahiti, the fafafine in Niue, and the akava’ine in the Cook Islands (New Zealand AIDS Foundation, cited in “To Be Who I Am: Kia noho au ki toku ano ao,” a report by the New Zealand Human Rights Commission, 2007, p. 25), and . The Maori of New Zealand have several different terms for those whose gender identity is different from their sex assigned at birth, includingwhakawahine, whakaaehinekiri, tangata ira wahine, hinehi, and hineua (for transgendered women) andtangata ira tane (for trans men) (op cit.).

transman (tangata ira tane) & transwoman (hineua)

(Rebecca Swan photos for the New Zealand Human Rights Commission report on transgender discrimination, “To Be Who I Am”)

There is evidence that some of these proto-transgenderal figures in Pacific Islander societies played shamanic roles in their cultures’ spiritual traditions.

In examining the entire history of homoerotic and proto-transgenderal traditions in pre-modern Asian and Pacific Islander societies, we must not make the mistake of romanticizing such traditions or failing to recognize the significant differences between ‘them’ and ‘us’ — meaning contemporary queer LGBT/queer APIs, especially those of us in the diaspora. Those ancient traditions are embedded in societies which were not characterized by equality of age, gender or class relations, and many of the forms that homoeroticism and transgenderal identity took would offend our egalitarian sensibilities.

The important point is that we as LGBT/queer APIs must known the history of our predecessors in order to counter the narrative of LGBT and queer as foreign, white, Western, and even specifically North American; only in doing so can we reinsert ourselves in the governing narratives of our countries, cultures and communities of origin. That is an imporant lesson for queer APIs; as I say, it is not that we should necessarily identify with the paksu mudang or the bissu or the hijra; rather, that examining such figures, we as queer APIs can re-envision ourselves in the light of such figures as both API and LGBT/queer. In other words, examining such proto-transgenderal shamanic figures from pre-modern Asian and Pacific Islander cultures can help those of us who are queer APIs to engage in identity formation in a way that avoids the binary opposition of LGBT = white/API = non-LGBT; it enables us to re-envision ourselves as queer and API by pointing to predecessors in our cultures of origin.

But the implications are not merely for individual identity formation but also for community construction; pointing to proto-transgenderal figures and images can enhance the sense of community among contemporary queer APIs and especially transgendered APIs; examination of such figures and images can even have implications for political action by challenging and disarming the false discourse of reactionary elements in the Asia/Pacific region today and in API immigrant communities that attempt to label LGBT identities as false and foreign, the fabrication of white, Western and even specifically American influence.

The Taliban represent an extreme example of a profoundly homophobic and transgenderphobic as well as misogynistic phenomenon that attempts to link homosexuality and transgender (which they invariably conflate) with Western influence and counterpose LGBT identities with adherence to religious faith, but there are examples to be found throughout the Asia/Pacific region of reactionary religious and political forces that reify this binary opposition and use it to oppress LGBT people. Images of proto-transgenderal figures can be deployed strategically to counter this false narrative by pointing to the important and in some cases even central role that these shamanic figures played in the spiritual traditions of pre-modern Asian and Pacific Islander societies.

Finally, and not least of all, examination of these proto-transgenderal figures can help queer APIs of all faith traditions to connect with a deeper level of spirituality by integrating their sexual orientation and/or gender identity and expression with their religious faith and/or spirituality. The binary opposition of the sacred and the profane which runs as a theme throughout the histories of many cultures has set up a false dichotomy that many LGBT people, including queer APIs, have deeply internalized. In examining the shamanic roles played by these proto-transgenderal figures, we as contemporary queer APIs can understand ourselves and our sexuality and gender identity and expression as something not intrinsically opposed to the religious or the spiritual, but instead as a very expression of the divine within; that can be true regardless of our religious affiliation or spiritual tradition, whether that be Christian, Muslim, Buddhist, Taoist, pagan, animist, or other.

The important truth is that the queer self can be the sacred self just as sacred texts can be queer and queered; so let us reclaim the sacred space which is our birthright as queer APIs; let the goddess within come out~!

Pauline Park is chair of NYAGRA, the New York Association for Gender Rights Advocacy (nyagra.com), a statewide transgender advocacy organization that she co-founded in 1998. She also co-founded Queens Pride House (the LGBT community center of Queens) in 1997 and currently serves as president of the board of directors and acting executive director. Park co-founded Iban/Queer Koreans of New York in 1997 and served as its coordinator from 1997 to 1999. Park led the campaign for the transgender rights law enacted by the New York City Council in 2002. In 2005, she became the first openly transgendered grand marshal of the New York City Pride March. She did her B.A. at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, her M.Sc. at the London School of Economics and her Ph.D. at the University of Illinois at Urbana. Park has written widely on LGBT issues and has conducted transgender sensitivity training sessions for a wide range of organizations. She was the subject of “Envisioning Justice: The Journey of a Transgendered Woman,” a 32-minute documentary that premiered in 2008.

한국

3 thoughts on “Transgender Identities & Spiritual Traditions in Asia & the Pacific: Lessons for LGBT/Queer APIs (Pacific School of Religion, 4.2.13)”

Dear Pauline-

This is just a marvelous piece of writing & research!! My M. Div. Thesis, ‘The Yoga of the Queer Religious Experience.” has similar content with an emphasis on the documented actual ‘religious/spiritual’ experiences of about 10-15 Queer identified persons.

We will definitely be in touch with you.

Best always;

Dina

An eye openner. Being ignorant of this subject in the past. A really interesting piece of writing & research. Non mention or recorded in most of the scripts that I have read. Really appreciate this eventhough just found this article in Feb 2017.

Fabulous article. Thank you.