Transgender Health Care: What Hospital-Based Providers Need to Know

Pauline Park, Ph.D.

Chair, New York Association for Gender Rights Advocacy (NYAGRA)

St. Barnabas Hospital

Embrace Healthcare Equality: Introducing Our LGBTQ Initiative

11 October 2013

I’m honored by the invitation to speak here at St. Barnabas Hospital and I’m especially honored to keynote the Embrace Healthcare Equality: Introducing Our LGBTQ Initiative event today. I would like to thank the LGBT diversity subcommittee for the invitation and I would especially like to thank Dr. Rory Sweeny McGovern, who was instrumental in introducing me to this hospital. Rory and I worked together as part of a transgender health care task force at St. Vincent’s Hospital for several years and I think we and our colleagues did great things together, including organizing the first transgender sensitivity training sessions for any major hospital in this city.

Let me begin by commending you for your commitment to ensuring full access to health care here at St. Barnabas for all members of our community. But let me also add that doing so will require a very significant commitment of resources — both time and financial — to attain that objective. Since founding Queens Pride House — the only LGBT community center in the borough of Queens in 1997 and the New York Association for Gender Rights Advocacy (NYAGRA) in 1998, I have been involved with work on access to health care for members of the LGBT community in a variety of capacities; one of the most important of these has been the Transgender Health Initiative of New York, a community organizing project established to ensure that transgendered and gender non-conforming people can access health care in a safe, respectful and non-discriminatory manner.

The transgender sensitivity trainings that we did at St. Vincent’s was an important expression of that commitment, and they helped create a model for what can be done at any hospital in this city or this country. Another important part of that work was the creation and publication in July 2009 of the NYAGRA transgender health care provider directory, the first directory of transgender-sensitive health care providers in the New York City metropolitan area and the first directory of transgender-sensitive health care providers published in print format anywhere in the United States. I continue to update that directory on nyagra.com.

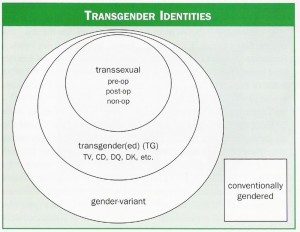

Transgendered and gender-variant people face pervasive discrimination in attempting to access health care in the United States. Some of the impediments to accessing quality health care are obvious and some are not. In order to understand those impediments and how to address them, it is first necessary to understand the community that we are discussing — hence the NYAGRA ‘circles diagram’ that I created way back in 1999 when we began the campaign for the the transgender rights law bill that was ultimately enacted into law by the New York City Council in 2002. I have used this diagram to illustrate in as simple a way as possible a diverse and complex community.

Briefly, the three circles include transsexuals — those who seek or have obtained sex reassignment surgery (SRS); those whom I will call ‘the transgendered’ — those who present fully in a gender not associated with their sex assigned at birth at least part of the time; and the gender-variant — including relatively feminine males who may still identify as men and boys and relatively masculine females who may still identify as women and girls. It is important to note here that this is a map of the gender universe and does not directly refer to sexual orientation; there are those in each of these circles who may identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual as well as those who may identify as heterosexual. In contrast to those in these three circles, the majority in any society are conventionally gendered — a majority of whom are undoubtedly heterosexual, but a significant minority of whom may be lesbian, gay or bisexual.

While addressing the conflation of sexual orientation with gender identity and gender expression is an important and indeed crucial part of the process of educating health care providers and the general public on transgender issues, it is also true that addressing discrimination based on gender identity and gender expression will go a long way towards addressing discrimination against LGB people because so much of that is based on the gender expression of gender-variant LGB people.

So how can we ensure full access to health care access for all members of the LGBT community here at St. Barnabas? Based on my own experience as an activist, advocate and consumer of health care, here are ten simple rules that I would like to suggest that we consider:

Rule #1: Effective health care provision requires the construction of a relationship of trust and confidence between the provider and the patient/client/’consumer.’ It is the responsibility of providers to educate themselves on issues of gender identity and gender expression in order to serve their patients, clients, and consumers sensitively and effectively. Conversely, it is also the responsibility of transgendered and gender-variant people to do what they can to educate and empower themselves and work with health care providers in order to obtain the best health care that they can.

Rule #2: Effective health care provision requires that providers take into account the diversity of the transgender community, which is extraordinarily diverse — in terms of gender identity and expression as well as race, ethnicity, religion, dis/ability, and sexual orientation. There are as many ways of being transgendered as there are transgendered people.

Rule #3: Health care providers need to understand that sex reassignment surgery (SRS) is not the end point for most gender transitions. Most transgendered people do not want SRS and most who do never get it. There are as many ways of transitioning as there are transgendered people.

Rule #4: Transgendered and gender-variant people are denied care in many areas not directly or even indirectly related to their gender identity; any attempt to address health care provision for members of the community must address those areas not related to gender transition as well as those areas that are transition-related. Some transgendered people are denied coverage for treatments or procedures that relate to their anatomical or biological sex assigned at birth, such as prostate cancer for transgendered women or cervical or ovarian cancer for transmen. Only in a relationship of mutual trust and respect can physicians and other health care providers be sensitive and informed enough to provide effective care in such areas.

Rule #5: The impediments to health care access are both medical and non-medical and effective health care provision requires that providers take into account and address both sets of impediments. Transgender sensitivity training should focus primarily on the psychosocial aspects of the interaction between providers and consumers, and that training should extend to physicians and nurses as well as everyone in a health care facility.

Rule #6: Health care providers need to avoid pathologizing transgendered people through the false diagnosis of gender identity disorder (GID) while at the same time understanding that such diagnoses are used by some transgendered people to access hormone replacement therapy (HRT), sex reassignment surgery (SRS) and other desired medical interventions.

Rule #7: Transgender sensitivity training needs to be mandatory for all staff in hospitals and health care-providing facilities, including technical people, security guards, and intake staff as well as medical and mental health professionals; physicians should undergo psychosocial sensitivity training, regardless of participation in ‘grand rounds’ and other cognate medical trainings and discussions. Transgender sensitivity trainings should be no less than two hours in duration and ideally should be four hours long. Real training involves an intensive interaction between the trainer and the trained. Webinars and handouts may be used to supplement such trainings but can be no substitute for trainings themselves. Trainings should be conducted by those who have specific expertise in transgender issues, not merely those who do general ‘diversity’ trainings or even those who do LGBT trainings but who lack expertise on transgender issues specifically. Given staff turnover, trainings must be conducted at regular intervals.

Rule #8: All health care providers and health care-providing facilities should adopt policies and protocols that specifically prohibit discrimination based on gender identity and gender expression in the provision of health care, and such policies and protocols should be regularly and effectively communicated to all relevant constituencies.

Rule #9: Health care providers should participate in larger efforts to achieve legal and public policy change in order to provide effective and universal health care for all, including all transgendered and gender-variant people; providers need to understand that the denial of health care to transgendered and gender-variant people is part of a larger denial of health care access to and insurance coverage and payment for health care to LGBT people, low-income people, poor people, and people with disabilities in the United States.

Rule #10: There are no rules, only ‘best practices’ — or at least, better practices and worse practices; and such practices must be informed by the lived experiences of transgendered and gender-variant people.

Now, every hospital is different and every set of health care providers is unique; but these ten rules, it would seem to me, can be applied anywhere, including here at St. Barnabas. By coming here to this auditorium, you have taken the first step in helping make this real. But as I have said, it is training that is arguably the most important and indeed crucial element in making it real and attaining an objective that I believe we all share. I congratulate you all and I especially commend the LGBT diversity subcommittee for organizing the launch of the LGBTQ Initiative today and I look forward to working with you all in helping make St. Barnabas the fully welcoming and inclusive hospital that I know it can be. That goal is within our grasp and we simply need to seize the opportunity to make it real. Carpe diem. Thank you.

* * * * *

Pauline Park is chair of the New York Association for Gender Rights Advocacy (NYAGRA), which she co-founded in 1998, and president of the board of directors as well as acting executive director of Queens Pride House (the LGBT community center in the borough of Queens), which she co-founded in 1997. Dr. Park led the campaign for passage of the transgender rights law enacted by the New York City Council in 2002. She served on the working group that helped to draft guidelines — adopted by the Commission on Human Rights in December 2004 — for implementation of the new statute. Park negotiated inclusion of gender identity and expression in the Dignity for All Students Act, a safe schools law enacted by the New York state legislature in 2010, and the first fully transgender-inclusive legislation enacted by that body, and she is a member of the statewide task force created to implement the statute. She also served on the steering committee of the coalition that secured enactment of the Dignity in All Schools Act by the New York City Council in September 2004. In 2004, Dr. Park named and helped create the Transgender Health Initiative of New York, a community organizing project established to ensure that transgendered and gender non-conforming people can access health care in a safe, respectful and non-discriminatory manner. And as executive editor, she oversaw the creation and publication in July 2009 of the NYAGRA transgender health care provider directory, the first directory of transgender-sensitive health care providers in the New York City metropolitan area and the first directory of transgender-sensitive health care providers published in print format anywhere in the United States. Dr. Park did her B.A. in philosophy at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, her M.Sc. in European Studies at the London School of Economics and her Ph.D. in political science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She has written widely on LGBT issues and has conducted transgender sensitivity training sessions for a wide range of organizations, including the New York State Affirmative Action Advisory Council (AAAC), the Association of Vocational Rehabilitation in Alcoholism and Substance Abuse (AVRASA), the Latino Commission on AIDS, the Park Slope Safe Homes Project, and the Queer Health Task Force at Columbia University Medical School. In addition to presenting at the HIV Grand Rounds lecture series of the Bureau of HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Dr. Park co-facilitated the first transgender sensitivity training sessions for any major hospital in New York City at St. Vincent’s Hospital Manhattan. In 2005, Dr. Park became the first openly transgendered grand marshal of the New York City Pride March. She was the subject of “Envisioning Justice: The Journey of a Transgendered Woman,” a 32-minute documentary about her life and work by documentarian Larry Tung that premiered at the New York LGBT Film Festival (NewFest) in 2008. In 2009, Dr. Park was designated ‘a leading advocate for transgender rights in New York’ on Idealist.org’s ‘New York 40’ list. In October 2012, Dr. Park was one of 54 individuals named to a list of ‘The Most Influential LGBT Asian Icons’ by the Huffington Post. In November 2012, she was named to a list of ’50 Transgender Icons’ for the Transgender Day of Remembrance 2012.