Joan of Arc & the uses & misuses of history: LGBT/queer historiography

by Pauline Park

The writing of transgender and queer history is an important component of the project of transgendering the academy, but it is one fraught with peril, conceptual and otherwise. The peril is particularly apparent when activists engage in the writing of that history, as so much of activist discourse is theoretically uninformed and burdened with an overly concretized identitarian politics that lacks conceptual sophistication, to the detriment of the work of the activists and organizations who engage in such discursive practices. Many activists treat LGBT identities as if they are eternal essences with no significant variance across time and place, claiming ‘famous homosexuals in history’ as if Leonardo da Vinci were just another Chelsea Boy or Castro Street Clone.

The transgender variant of this essentializing of identity and identity politics is exemplified by the characterization of Joan of Arc as just one in a long line of ‘Transgender Warriors’ (to cite the title of Leslie Feinberg’s 1996 book), as if there were no significant differences in the social construction of (trans)gender identity in France in 1430 or in New York City in 1969 or 2010, for that matter. To describe Joan of Arc as “an inspirtational role model — a brilliant transgender peasant teenager leading an army of laborers into battle” (p. 36) who was “burned at the stake by the Inquisition of the Catholic Church because she refused to stop dressing in garb traditionally worn by men” (p. 31) is to use history for contemporary political purposes. Not only does the “Transgender Warriors” approach to history take an individual historical figure such as Joan of Arc entirely out of historical context — failing to acknowledge that the central reason for her execution by the English was her military leadership of the enemy French forces — that approach produces rather bizarrely ironic discursive practices, constructing a transgender hero out of a woman who in contemporary France is beloved by the far right as the very epitome of French nationalism. But such is the danger of writing transgender history to advance a contemporary political agenda.

In the introduction to “Monsieur d’Eon is a Woman: A Tale of Political Intrigue and Sexual Masquerade,” the biography of the Chevalier d’Eon by Gary Kates, he writes in describing Feinberg’s approach to transgender history, “…such theorists have little historical sensibility” (preface, p. xiii). Those transgendered individuals who know of d’Eon, “think of d’Eon as an early pioneer who somehow lived centuries ahead of his time. But what makes d’Eon fascinating is that he was no such thing. Neither sick nor ahead of his time, d’Eon’s gender bending was lionized in his day and even made emblematic of his generation,” Kates writes. An example of historically informed transgender history a profile of the first public transgender figure in Western European history, the Kates biography of d’Eon avoids engaging in the kind of essentializing discourse in which a good deal of transgender history and a great deal of trransgender activism engages.

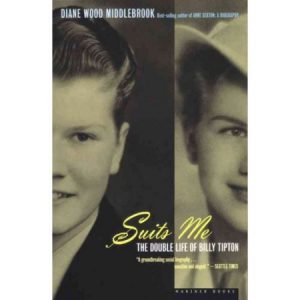

One does not need to endorse the notion that all history is reducible to biography to see that biography is an important component of the project of transgender history. Nor does one need to be transgendered oneself to write transgender biography or history, but the non-transgendered biographer and historian need to be aware of and sensitive to the self-understanding of the subjects that they write about. To call Billy Tipton “the producer of the illusion of masculinity, both onstage and off” — as Diane Wood Middlebook does in her biography of the twentieth century jazz artist (“Suits Me: The Double Life of Billy Tipton,” Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1998) comes close to imposing a misunderstanding of a subject whom contemporary transgendered people would doubtless wish to call a ‘transman.’

But the danger with autobiography as history is the risk that transgendered authors may project their own individual self-construction on the community as a whole, generalizing from direct personal experience in a universalizing discourse that actually undermines those activists and academic theorists who are attempting to communicate the full diversity and complexity of the universe of gender and transgender identity to a largely uncomprehending society.

Of course if by ‘history’ we mean the writing of human history by human beings, ‘history’ is most certainly a social construction in a very real sense; and granted that there is no such thing as absolute objectivity, no ‘Archimedean point’ from which a completely neutral observer can write about human history without any investment in any group, community or structure, whether racial, religious or gender-based; but If history is to have any legitimate use, the writing of it must in some very real sense be based on some empirical observation or investigation independent to at least some extent of the writer(s) of that history; simply projecting one’s own identity or identities and desiderata back onto figures from the past cannot be accounted ‘history’ in any meaningful sense.

It is certainly legitimate to draw parallels between contemporary LGBT identities and past identities and practices and to look for antecedents for contemporary identities, as I have done in a presentation I first developed in 2011 (“Proto-Transgenderal & Homoerotic Traditions in Asia & the Pacific“); but in doing so, it is important to avoid simply appropriating past practices and identities for contemporary use — which is why I have created and employed the term ‘proto-transgenderal’ to describe pre-modern identities and practices to anticipate contemporary transgender identity.

Above all, it is important to avoid the extremes of either essentializing LGBT identity as unchanging and eternal as it is immutable or refusing to recognize any parallels or continuity whatsoever — arguing as a few social construction theorists do that contemporary LGBT identities have absolutely no precedent and that any reference to homosexuality or transgender in any form before the late nineteenth century is simply archaism. The task then is to take history seriously, something worthy of study, investigation and thought, recognizing as we must that while we can never fully put ourselves in the position of those who lived in previous eras — especially in cultures and societies radically different from our own — that contrariwise we need not consign ourselves to a white, upper-middle-class, US-centric perspective. Transgender studies as a field advances when we get history ‘right,’ to the extent that we can.

Pauline Park (paulinepark.com) is chair of the New York Association for Gender Rights Advocacy (NYAGRA) (nyagra.com), a statewide transgender advocacy organization that she co-founded in 1998, and president of the board of directors and acting executive director of Queens Pride House (queenspridehouse.org), which she co-founded in 1997.

Park named and helped create the Transgender Health Initiative of New York (THINY), a community organizing project established by TLDEF and NYAGRA to ensure that transgendered and gender non-conforming people can access health care in a safe, respectful and non-discriminatory manner. And as executive editor, she oversaw the creation and publication in July 2009 of the NYAGRA transgender health care provider directory, the first directory of transgender-sensitive health care providers in the New York City metropolitan area and the first directory of transgender-sensitive health care providers published in print format anywhere in the United States.

Park led the campaign for passage of the transgender rights law enacted by the New York City Council in 2002. She served on the working group that helped to draft guidelines — adopted by the Commission on Human Rights in December 2004 — for implementation of the new statute. Park negotiated inclusion of gender identity and expression in the Dignity for All Students Act (DASA), a safe schools law enacted by the New York state legislature in 2010, and the first fully transgender-inclusive legislation enacted by that body, and she is a member of the statewide task force created to implement the statute. She also served on the steering committee of the coalition that secured enactment of the Dignity in All Schools Act by the New York City Council in September 2004.

Park did her B.A. in philosophy at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, her M.Sc. in European Studies at the London School of Economics and her Ph.D. in political science at the University of Illinois at Urbana. Park has written widely on LGBT issues and has conducted transgender sensitivity training sessions for a wide range of organizations. In 2005, Park became the first openly transgendered grand marshal of the New York City Pride March. She was the subject of “Envisioning Justice: The Journey of a Transgendered Woman,” a 32-minute documentary about her life and work by documentarian Larry Tung that premiered at the New York LGBT Film Festival (NewFest) in 2008. In April 2013, Park was named to the inaugural Trans 100 list of leading activists and community members.