By Pauline Park

* * * * *

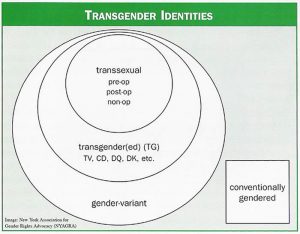

Pauline Park is chair of the New York Association for Gender Rights Advocacy (NYAGRA), which she co-founded in 1998, and president of the board of directors as well as acting executive director of Queens Pride House (the LGBT community center in the borough of Queens), which she co-founded in 1997. Dr. Park led the campaign for passage of the transgender rights law enacted by the New York City Council in 2002. She served on the working group that helped to draft guidelines — adopted by the Commission on Human Rights in December 2004 — for implementation of the new statute. Park negotiated inclusion of gender identity and expression in the Dignity for All Students Act, a safe schools law enacted by the New York state legislature in 2010, and the first fully transgender-inclusive legislation enacted by that body, and she is a member of the statewide task force created to implement the statute. She also served on the steering committee of the coalition that secured enactment of the Dignity in All Schools Act by the New York City Council in September 2004. In 2004, Dr. Park named and helped create the Transgender Health Initiative of New York, a community organizing project established to ensure that transgendered and gender non-conforming people can access health care in a safe, respectful and non-discriminatory manner. And as executive editor, she oversaw the creation and publication in July 2009 of the NYAGRA transgender health care provider directory, the first directory of transgender-sensitive health care providers in the New York City metropolitan area and the first directory of transgender-sensitive health care providers published in print format anywhere in the United States. Dr. Park did her B.A. in philosophy at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, her M.Sc. in European Studies at the London School of Economics and her Ph.D. in political science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She has written widely on LGBT issues and has conducted transgender sensitivity training sessions for a wide range of organizations, including the New York State Affirmative Action Advisory Council (AAAC), the Association of Vocational Rehabilitation in Alcoholism and Substance Abuse (AVRASA), the Latino Commission on AIDS, the Park Slope Safe Homes Project, and the Queer Health Task Force at Columbia University Medical School. In addition to presenting at the HIV Grand Rounds lecture series of the Bureau of HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Dr. Park co-facilitated the first transgender sensitivity training sessions for any major hospital in New York City at St. Vincent’s Hospital Manhattan. In 2005, Dr. Park became the first openly transgendered grand marshal of the New York City Pride March. She was the subject of “Envisioning Justice: The Journey of a Transgendered Woman,” a 32-minute documentary about her life and work by documentarian Larry Tung that premiered at the New York LGBT Film Festival (NewFest) in 2008. In 2009, Dr. Park was designated ‘a leading advocate for transgender rights in New York’ on Idealist.org’s ‘New York 40’ list. In October 2012, Dr. Park was one of 54 individuals named to a list of ‘The Most Influential LGBT Asian Icons’ by the Huffington Post. In November 2012, she was named to a list of ’50 Transgender Icons’ for the Transgender Day of Remembrance 2012.Pauline Park is chair of NYAGRA, the New York Association for Gender Rights Advocacy (nyagra.com), a statewide transgender advocacy organization that she co-founded in 1998. She also co-founded Queens Pride House (a center for the LGBT communities of Queens) in 1997 and currently serves as president of the board of directors. Park co-founded Iban/Queer Koreans of New York in 1997 and served as its coordinator from 1997 to 1999. She also serves as vice-president of the board of directors of the Transgender Legal Defense & Education Fund (transgenderlegal.org). Park led the campaign for the transgender rights law enacted by the New York City Council in 2002. In 2005, she became the first openly transgendered grand marshal of the New York City Pride March. She did her B.A. at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, her M.Sc. at the London School of Economics and her Ph.D. at the University of Illinois at Urbana. Park has written widely on LGBT issues and has conducted transgender sensitivity training sessions for a wide range of organizations. She was the subject of “Envisioning Justice: The Journey of a Transgendered Woman,” a 32-minute documentary that premiered in 2008.