Andrew Ahn’s “The Wedding Banquet”

Pauline Park

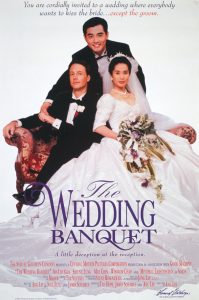

“The Wedding Banquet” was a signal moment in the history of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and questioning (LGBTQ) Asian & Pacific Islander (API) community: when Ang Lee’s film was released in 1993, queer APIs were featured in a major Hollywood motion picture.

Winston Chao played the more or less openly gay Taiwanese immigrant Gao Wai-Tung living in New York with his white partner Simon (played by Mitchell Lichtenstein); but to please Gao’s very traditional Taiwanese Chinese parents, they pretend that their tenant Wei-Wei recently arrived from mainland China is actually Gao’s fiancée, leading to a wildly rambunctious traditional Chinese wedding banquet and surprising complications; eventual parental acceptance of the actual truth provides the happy dénouement along with complications from Gao’s nuptial interactions with Wei-Wei.

I honestly did not think Ang Lee’s wonderful film could be improved upon until I saw Andrew Ahn’s remake at a special preview for queer API community members. When it comes to the new “Wedding Banquet,” the term ‘remake’ seems inadequate: Ahn’s film is a loving tribute to Lee’s but really more than just a remake — it is (to use Ahn’s own word) a ‘re-imagining’ of the Ang Lee classic.

Instead of a ‘rice and potato’ couple, there is a gay Chinese American and a gay Korean American and a lesbian couple one of whom is Chinese American and the other Native American. Bowen Yang (of “Saturday Night Live” fame) plays the non-dissertating Chris and Han Gi-chan plays the textile-talented Korean immigrant Min while Lily Gladstone is the indigenous-identified Lee who is undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF) and Kelly Marie Tran plays her ‘soft butch girlfriend Angela. Joan Chen plays Angela’s too PFLAG-perfect mother May Chen and Young Yuh-jung plays Min’s formidable grandmother Ja-Young. If this film were an episode of “The Weakest Link,” it would be impossible to identify anyone as a weak link as all six leads are superb. I will always remember Joan Chen as Puyi’s empress in Bernardo Bertolucci’s “The Last Emperor”; here, she plays a mother too wrapped up in her own PFLAG stardom to address her daughter’s simmering resentment against her; their reconciliation is just one of the scenes that proves that Chen fully deserves her status as one of the most admired Asian actresses of our day.

But for me, the scene in which Ja-Young recognizes her grandson’s artistic talent as well as revealing a deep secret about her relationship with him as well as with her husband is the touchstone of the film’s genius and Academy Award-winning Youn Yuh-jung brings to the scene an extraordinary sensitivity and skill; to me, this scene is the emotional core of the heart of “The Wedding Banquet.”

Of course you will laugh at least as much as you will cry and the traditional Korean wedding is one of the funniest scenes in the film; but it is a measure of Ahn’s adroit handling of the material of the screenplay he wrote with James Schamus that Ahn can extract laughs while still showing the utmost respect and even reverence for the ceremony itself.

And in fact, while Ang Lee’s film was firmly rooted in the Sinitic cultural world, Ahn significantly Koreanizes the scenario by making the driving premise of the film the need for Min to please his (entirely unseen) Korean grandfather back in Korea through a heteronormative marriage. But Ahn also updates the scenario to the present day where — unlike in the world of Ang Lee’s 1993 film — same-sex couples can legally marry and have children with both partners legally recognized as parents. And so the climactic scene at City Hall becomes the historically updated riposte to the original film with the marriage license actually available to Min and Chris as well as Min and Angela.

One does not need to be LGBTQ — much less queer API — to fall in love with this film; but I think queer APIs will especially appreciate the subtle humor of the movie’s articulation of the fault lines in Chinese and Korean —and Chinese American and Korean American —culture and their intersection with contemporary queer culture and identity. While there are plenty of contemporary references from the United States c. 2025, there is an emotional heart and an adroit dramaturgy here that I am guessing will stand the ‘test of time’; I am guessing that this film will bring knowing smiles and tears to audiences long after all of those watching it in 2025 have passed from the scene.

Pauline Park is an LGBT activist based in Queens who co-founded Iban/Queer Koreans of New York — the first organization for LGBT/queer Koreans in the city — in January 1997 and led it as coordinator until May 1999; she has written widely on LGBT issues and queer API history and identity and was the first transwoman of Asian descent to lead an LGBT community center in the United States as executive director when she served in that capacity from 2012 to 2015.

Gay City News published this review on 21 April 2025 under the title “Andrew Ahn’s ‘The Wedding Banquet’ is a loving tribute to Ang Lee’s original film.”