Today is the 30th anniversary of the Argentine invasion of the Falkland Islands (Las Malvinas), and no one at the time could have predicted what an extraordinary impact it would have. I was living in London in 1982, and as shocked as anyone by the turn of events, including Margaret Thatcher’s decision to send the British navy to retake the islands, which I opposed.

The news media in the United States played the whole affair as a comic Gilbert & Sullivan operetta and a bit of a farce, but the war was anything but “HMS Pinafore” for the British and Argentine soldiers who fought it or for the political leaders who had gambled first on the invasion — Gen. Leopoldo Galtieri, the unelected president of the Argentine Republic and the head of the junta that ran the military dictatorship — and Thatcher, elected in 1979 and the first (and so far, only) woman to serve as British prime minister.

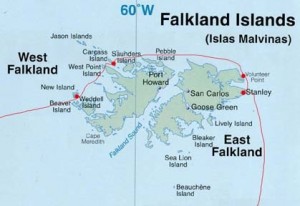

The enormous distance between Britain and the Falklands, and the relative proximity of Las Malvinas to Argentina, gave that country a considerable military advantage. But on May 2, the British torpedoed and sank the General Belgrano, an Argentine warship; even many in the United Kingdom who supported the war effort (which I did not) were shocked and horrified by the loss of 323 Argentinian lives, many of them young men in their teens or twenties. The Reagan administration may have provided direct intelligence support in the targeting of the Belgrano (Julian Borger, “US feared Falklands war would be ‘close-run thing,’ documents reveal,” Guardian, 4.1.12).

The final British military victory against great odds was rather improbable, but when it came, it made Thatcher into the Iron Lady and saved her political career (as Simon Jenkins notes in “Falklands war 30 years on and how it turned Thatcher into a world celebrity,” Guardian, 4.2.12) rescuing her from deep unpopularity and helping her lead the Conservative Party to victory in 1983 (which I witnessed first-hand) and 1987 (which I observed from back in the US). The result was another nine years of aggressively right-wing anti-labor, anti-gay policies from a prime minister unconstrained by separation of powers or virtually any other institution in British government or society — especially given the support of the British press, largely controlled by the right-wing Australian billionaire Rupert Murdoch.

At the same time, the Argentine defeat led to the fall of the military junta and the establishment of democracy in Argentina, which was an outcome unanticipated by both Thatcher and Galtieri; certainly, there was nothing in Thatcher’s thinking or public statements that indicated that the establishment of democracy in Argentina played any role in her political calculations.

So the British military victory had largely negative consequences for the United Kingdom in terms of Thatcherism unbounded and a rise of British jingoism of the worst sort, but positive consequences for Argentina because of the collapse of support for the military dictatorship, which led to the ouster of the junta and the emergence of democracy there. History is like that: actions taken having entirely unintended but potentially enormous consequences…