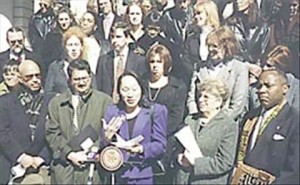

On the steps of City Hall at the press conference on 29 February 2000 announcing the public launch of the campaign for Int. No. 24, the New York City transgender rights bill. Front row: Council Member Margarita Lopez, Council Member Philip Reed, Juan Figueroa (executive director of the Puerto Rican Legal Defense & Education Fund), Pauline Park, Council Member Ronnie Eldridge, Council Member Bill Perkins. Second row: Charles King (executive director, Housing Works), Carrie Davis, Council Member Gifford Miller, Melissa Sklarz, Donna Cartwright, Council Member Christine Quinn.

A history of the New York Association for Gender Rights Advocacy (NYAGRA)

Part I: the founding (1998-2000)

Of all the organizations that I have been involved with, I am probably most closely associated in the public mind with NYAGRA.

The idea for the organization now known as the New York Association for Gender Rights Advocacy (NYAGRA) originated in a conversation that I had with Paisley Currah in May 1998. Paisley and I drove down to Washington D.C. for GenderPAC’s national lobby day, the second that we would participate in. While on the drive back up, Paisley turned to me and said, “You know, Pauline, we can do this in New York.” Paisley (who at that point was still using feminine pronouns but who transitioned several years later) pointed out that there was not a single transgender advocacy organization in the state that was actively engaged in the legislative arena.

I pointed out that I was at that moment on the board of directors of Queens Pride House, on the steering committee of Gay Asian & Pacific Islander Men of New York (GAPIMNY), and coordinator of Iban/Queer Koreans of New York (Iban/QKNY). In short, I honestly felt that I did not have the time to get involved with founding another organization. But Paisley persisted, and I agreed to help her with the new organization as long as I did not end up as its leader. Paisley’s organizational experience at that point was limited to participation in the Ithaca chapter of ACT-UP, a non-organization of an organization, and so her desire for my active involvement was perfectly understandable.

Paisley asked me to come up with a name for the organization, and so I thought through various possibilities, all of which had to have ‘New York’ and ‘Gender’ in them. It seemed to me that an actual acronym that spelled a word would be more effective and more memorable than a mere abbreviation. After much mental gymnastics, I eventually came up with ‘New York Association for Gender Rights Advocacy,’ which conveniently spelled ‘NYAGRA.’ That acronym evokes images of Niagara Falls, of course, which is a universally recognized landmark in the state. Paisley loved the name, and so did the other activists who attended our first meeting.

Paisley and I conferred on the activists that we should invite to the first meeting, but she left it to me to convene the meeting, which I did on June 30. David Valentine served as the gracious host for that historic first meeting, though his apartment in Greenwich Village unfortunately lacked air conditioning. Seven of us gathered around 1:30 p.m. on that hot June day in 1998: Paisley, David, and me, along with four others. Rosalyne Blumenstein was then the director of the Gender Identity Project at the Lesbian & Gay Community Services Center (since renamed the LGBT Community Center) and as such was at that moment far and away the best-known and most prominent transgender activist in the city. Carrie Davis was a peer counselor at the GIP and would succeed Roz as director a few years later. David was at that time a Ph.D. candidate at New York University and was actually working on a dissertation on transgender. Paisley was at that point an assistant professor of political science on tenure track at Brooklyn College. Donna Cartwright was a copy editor at the New York Times.

Roz left the new organization after a dispute over her role in it. NYAGRA working group members decided to hold a meeting on October 24, concurrent with the TransWorld conference at the Audre Lorde Project in Brooklyn. TransWorld was the first conference by and for transgendered people of color in New York (and anywhere in the United States, as far as I knew), and it was jointly sponsored by ALP (a community center for LGBT people of color) and the GIP; given the GIP’s sponsorship, TransWorld was billed as the fourth in a series of transgender conferences organized under the auspices of the Center and the GIP (‘transexual/transgender health empowerment conferences,’ as the conference promotional material described them).

Until the founding of NYAGRA in June 1998, the GIP had been ‘the only game in town,’ as it were, when it came to transgender advocacy in New York City, and the director of the GIP had been the ‘go-to girl’ for media comment on transgender-related public policy issues as well as social services in the city. As such, Roz carried a great deal of weight; but she harbored resentments against those she felt – rightly or wrongly – had slighted her, and she made clear to those present at the NYAGRA meeting that October 24 that she wanted to use NYAGRA to punish Tim Sweeney for what she had perceived to have been a slight to her.

At the founding meeting on June 30, members had reached consensus about approaching the Empire State Pride Agenda to try to secure transgender inclusion in the Sexual Orientation Non-Discrimination Act (SONDA) then pending in the New York state legislature. As deputy director of the Pride Agenda (or ‘ESPA,’ as everyone outside the Pride Agenda called it), Tim Sweeney would be a key interlocutor in the larger LGBT community; given that, it seemed to me foolish at best to commence any relationship with ESPA by needlessly offending its deputy director simply to redress a perceived slight pre-dating the founding of NYAGRA that had nothing to do with the organization’s legislative agenda, and I said as much to Roz. All of the founding members at the meeting and all of the new members who joined us at that October 24 meeting were in agreement on that point, and our refusal to allow Roz to use NYAGRA to prosecute her own personal political agenda – at the expense of the credibility and effectiveness of the new organization – prompted her to resign.

Fortunately, from that very first meeting (on June 30), there was an agreement that the primary mission of the organization should be to pursue transgender inclusion in legislation, especially in the Sexual Orientation Non-Discrimination Act (SONDA) and the hate crimes bill both pending in the New York state legislature. All seven activists present at the first meeting agreed on one point: our first inter-organizational meeting should be with the Empire State Pride Agenda. There would be no ‘getting around’ ESPA, which as the leading lesbian and gay political organization in the state, played a leading role in the New York State Hate Crimes Bill Coalition. When it came to SONDA, the Pride Agenda’s role was even more central: ESPA was founded (from the merger of two other organizations) specifically to get SONDA passed, and that gay rights bill was its flagship legislation.

And so on November 19 [check date], several activists representing NYAGRA met with Tim Sweeney (then ESPA’s deputy director) and Paula Ettelbrick (then ESPA’s legislative director) at the Pride Agenda’s office on Hudson Street in Manhattan. The NYAGRA contingent’s aim was to persuade the Pride Agenda to agree to amend both SONDA and the state hate crimes bill to add gender identity and expression in order to protect transgendered and gender-variant people from discrimination and hate crimes, respectively.

With regard to the latter legislation, Tim referred us to the New York State Hate Crimes Bill Coalition, which NYAGRA joined in January 1999; ESPA’s opposition to transgender inclusion in that bill would only become clearer in April 2000, as the bill headed for passage in the state Senate. As for SONDA, Tim stated unequivocally that ESPA was not prepared to consider transgender inclusion in their flagship legislation; he and Paula opined that members of the state legislature were simply not going to support transgender inclusion in the bill – a self-fulfilling prophecy coming from ESPA, as no legislator would brook their opposition to such inclusion. From ESPA’s perspective, we must have seemed like upstarts, a bunch of transgender activists without any experience in legislative work in Albany or even at the local level. And while the NYAGRA name would become famous, at that moment, in November 1998, we were indeed unknown as an organization without a proven track record in legislative work.

Instead, Tim made a ‘counter offer’ of sorts, proposing that the Pride Agenda work with NYAGRA on local non-discrimination legislation, a suggestion that we ultimately agreed to, after significant internal discussion. It was clear to everyone present on the NYAGRA side – including Paisley Currah, Donna Cartwright, David Valentine, Sophia Pazos, Lisa Maurer (who participated by phone from Ithaca) and myself – that ESPA simply would not be moved on the issue of SONDA and that – as a new group without any resources and without any relationships with key legislators – we had no leverage to move ESPA. It was the unanimous consensus of the founding members of NYAGRA to accept an understanding with ESPA that the two organizations would work together on a local transgender rights bill and defer the question of transgender inclusion in SONDA to a later day.

Meanwhile, the new organization required infrastructure, and an organizational website was one of the first pieces of infrastructure that we could see we would need at the dawn of the Internet age. Paisley had set up a website at www.nyagra.org, though no thought was given at the time that it was technically the webmaster who would therefore be in a position to claim ownership of the website, and not the organization, should a dispute arise over its provenance – as in fact did happen. Meanwhile, the working group began to communicate regularly by e-mail, and David would set up a listserve for the founding members.

Slowly but surely over the course of NYAGRA’s early years, members of the ‘working group’ would begin to construct the rudiments of an organizational framework. But the critical decision that the founding members made at the onset to establish a ‘come one, come all’ policy for the working group would come close to undermining the organization within a year of its founding.

While there was initial consensus on legislative approach, there was dissensus from the start about NYAGRA’s organizational structure from the very beginning. At our very first meeting, I proposed a traditional board structure. Not only did I have no desire to be either president or chair of the board of directors, I was hoping that Paisley would agree to accept the top leadership title. But Carrie Davis insisted that there be “no hierarcy” in NYAGRA’s organizational structure, and Donna Cartwright derided a board structure as being ‘corporate’ and therefore inconsistent with the ideals of the organization. Ironically, Carrie worked for an organization (the Center) that had a very hierarchical staff structure governed by a self-selecting board of directors (i.e., one not chosen by its members), Equally ironic, Donna would go onto serve on the board of directors of the National Center for Transgender Equality (NCTE) some years later without any compunction. But on that hot June day in 1998, Carrie and Donna carried the day, defeating my proposal for a traditional board. Donna insisted on calling the assembled activists the ‘working group,’ a moniker that I thought was inappropriate for an advocacy organization, and worse still, insisted that the working group be open to everyone.

Hence the working group, as de facto board of directors, was open to everyone, and no vote could be taken to exclude anyone, regardless of behavior. At the time, I had a strong feeling that the ‘come one, come all’ approach that Donna insisted on and that the other founding members agreed to could lead to serious problems, and that intuition was prescient. In fact, the open door policy would very nearly be the undoing of the organization.