Articulating Identity, Organizing Community

Re-Launching the Queer API Movement in the United States

Pauline Park

keynote speech

Launch

The 3rd Annual Queer & Asian Conference

University of California at Berkeley

1 May 2010

I would like to begin by thanking Cal Q&A and the committee members who organizers of the 3rd annual Queer & Asian conference for inviting me to speak here. I’d especially like to thank Charles Tsai for all of his work in helping to bring me here. I’m honored to be asked to keynote this conference and I’m delighted to have the opportunity to speak to you on the theme of ‘Launch,’ which I have made the theme of my speech.

QACON08’s theme was “Story-ing The Silence: Filling the Pages,” and QACON09’s theme was “Articulation: Animating Our Collective Autobiography.” QACON10’s mission statement declares:

“…It’s time now, to use the tools we have, our history, our storytelling, our wills and hearts to look forward and move together in solidarity. Continuing the conference tradition of strength through shared stories and experiences, the question now becomes how we can unify those stories into action. How can we build and unify a community to address the issues we face as a whole? How do we advance our trajectory with the networks we have built? How do we take concrete actions to make our presence as a community seen, heard, and felt?…”

What I would like to do is to attempt to answer those questions by linking the themes of identity and activism, talking about how an articulation of identity can provide the basis for effective activism and advocacy. I would like to begin with a brief look at the homoerotic traditions and proto-transgenderal identities and practices in pre-modern Asian and Pacific Islander (API) societies and their relevance for contemporary lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) identity construction in the United States. I will then look at the emergence of an LGBT/queer API movement through the development of queer API organizations in this country over the course of recent decades. Drawing from my own experience with several of those organizations, I will outline what I see as the major challenges facing queer API organizations and how we as a community can move forward to build a queer API movement that effectively advances our liberation as individuals and members of that community.

We’re Here, We’re Queer: Homoerotic Traditions & Proto-Transgenderal Traditions in Pre-Modern Asian & Pacific Island Societies

What could history — some of it genuinely ancient — possibly have to do with contemporary issues facing the queer API community, from marriage equality to transgender rights? Quite a lot, I would argue. Why? Because possibly the biggest misconception in API communities is that we are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgendered because we’ve been hanging around white people too much. The implicit assumption behind that misconception is one of a viral model of gender identity and sexual orientation. The implications for the struggle for LGBT rights are profound.

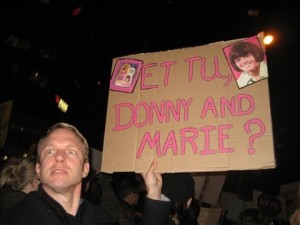

Here in California, of course, the debate over same-sex marriage has intensified over the last few years, culminating in the passage of Proposition 8 in November 2008. There has been a great deal of controversy over the apparently greater margin of victory for Prop 8 in communities of color, and some white queers have engaged in a very counterproductive discourse, waving placards with slogans such as ‘Gay is the new black.’ I was dismayed to see such signs held aloft in the enormous crowd that gathered in New York City on November 13 of that year to protest the passage of Proposition 8.

The role of the religious right in the passage of Proposition 8 was crucial, as both pro-8 and anti-8 forces would agree, and the ability of Mormons, evangelical Protestants, conservative Catholics, and other elements of the religious right to reach communities of color in particular played a pivotal role in the success of the campaign for Prop 8. And that brings us back to those homoerotic and proto-transgenderal traditions, identities and practices. Why? Because the discourse which the religious right successfully articulated in communities of color — including in API communities — was one which makes us foreign to our own cultures and communities of origin.

Ironically enough, as I have said, queer is in fact traditional in Asian and Pacific Islander cultures in a very meaningful sense. The slogan of Queer Nation was “We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it.” When it comes to homosexuality and transgender, the truth is that we have been here — in every Asian or Pacific Island society — since time immemorial.

China has homoerotic and proto-transgenderal traditions going back centuries. The ‘passion of the cut sleeve‘ (duan xiu) — the love of the Han dynasty Emperor Ai (27 BC-1 AD) — for his male favorite, Dong Xian — is the source of the Chinese euphemism for homosexuality (namely, ‘cut sleeve’). The other popular Chinese euphemism for homosexuality — the ‘half-eaten peach‘ — goes back even further, to the Zhou dynasty Duke Ling of Wei (534-403 BC) and his male lover, Mixi Zia. And there is that most gender-transgressive of Taoist deities, Guanyin, who is said by some to have changed from man to woman and who has become an iconic image for the gender-variant throughout East Asia.

In pre-modern Korea, the was a tradition of teenage ‘boy-wives’ whose marriages to adult men were recognized in the villages in which they lived. There were also the hwarang — youth in the Silla period who were members of squads of elite archers wore make-up and dressed in long, flowing women’s gowns. And of course, in the all-male namsadang theatrical troupes that toured villages throughout Korea until the early 20th century, the teenage boys played women’s roles — just as Elizabethan theater in England — and were said very often to be lovers of adult men in the same companies. Finally, there is the mudang — the shamanic figure in the original Altaic culture which Koreans brought down into the Korean peninsula with them from eastern Siberia. This pre-Sinitic mudang culture pre-dates the introduction of Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism into the peninsula. In the mudang culture, the shaman is always a woman, but not necessarily female: a significant number of mudang were male — paksu mudang — and evidence suggests that they may have lived as women as well as performing the sacred rites and rituals of the mudang.

While it is true that contemporary LGBT identities are of recent vintage, it is equally true that there were people in every pre-modern Asian or Pacific Islander society who were like us in important respects and whom we would call lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgendered. The binary opposition of LGBT people as secular atheists opposed to the God-fearing conservative Catholic Filipinos, fundamentalist Protestant Koreans, and ultra-traditional Hindu South Asians who are a significant part of the Asian diaspora in the United States is a false dichotomy, reinforced by the mainstream media who pit an invariably white queer activist calling for a complete separation of church and state against a minister or priest or lay person — often a person of color — in a false ‘debate’ over same-sex marriage.

Of course, the dangers of the propagation of this false dichotomy are apparent not only with regard to same-sex marriage, but every issue related to sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression in our society. So when we join the Chinese lunar new year parades — as we did in New York City’s Chinatown for the first time on Feb. 21 as the first LGBT contingent in that parade — we are simply reclaiming our rightful place in our communities of origin and reinscribing ourselves in the dominant narratives of Asian and Asian American cultures. What we must tell non-LGBT APIs who are shocked or confused by our participation in such events is this: we are you and you are us. We have been queer, we have been here (all along), and you have been used to it, you just forgot.

Acknowledging our queer Asian and Pacific Islander forbears, actually, is very much in the Asian and Pacific Islander tradition of honoring one’s ancestors. But at the same time that we recognize those forbears — so often erased from Asian and Pacific Island history writing — we must also recognize that there are significant differences between members of our contemporary queer API communities and those queer API forbears who anticipate our twenty-first century LGBT identities; that means resisting the temptation to appropriate such identities wholesale and without a full recognition of the differences that may separate us from the Indian hijra and the Sulawesi bissu transgendered shamans as well as the passage of centuries that may separate us from the Korean hwarang of the Silla dynasty.

We must also acknowledge the class, generational, and gendered aspects to those homoerotic and proto-transgenderal traditions that separate us from our queer forbears; and so we must resist the temptation of falling into an easy and naive romanticization of pre-modern traditions which will not and cannot meet contemporary feminist-informed progressive political standards. Let us rather invoke these icons as inspiration in the full realization of their imperfection and imperfect applicability to the identity constructions and issues of today.

Queering Asian, Asianing Queer: Movement in Emergence

The point of such an invocation must be not an end point in itself, but rather, the strategic deployment of such images in the reconfiguration of identity, which in turn may provide the basis for action. In other words, let us insist on the integrity of our identities as queer APIs who have no need to choose between the LGBT/queer and the Asian or Pacific Islander components of those identities.

The task for us as queer APIs must therefore be twofold: to ‘queer’ the notion of ‘Asian’ and ‘Asian American’ as well as to ‘Asian’ the notion of ‘queer.’ How do we do that? By establishing an API presence in the LGBT movement as well as a queer presence throughout API communities in the United States as well as back in our homelands of origin in the Asia/Pacific region. Here in the United States, just as back in Asian countries, there have been significant developments in that regard. In this country, the greatest progress has been made at the local level.

I am currently a member of both Q-Wave — the queer API women’s organization in New York City — and the Gay Asian & Pacific Islander Men of New York (GAPIMNY) and I served on the GAPIMNY steering committee in 1999 and 2000. I am also a member of the advisory committee of the Dari Project, which is in the process of developing materials to explain LGBT issues to Korean-speaking family members of queer Koreans. Here in the San Francisco Bay area, there is the Gay Asian Pacific Alliance (GAPA), Asian and Pacific Islander Family Pride, the Asian Pacific Islander Queer Women & Transgender Community, South Bay Queer & Asian (SBQA), and a host of student organizations at colleges and universities in the area, including Cal Q&A here at Berkeley, who have organized this conference. These local and student organizations are a crucial part of the infrastructure of queer API communities.

Until recently, however, we have had little presence or organizational infrastructure at the national level. The National Queer Asian Pacific Islander Alliance (NQAPIA) is the first national queer API organization in the United States, emerging out of a series of meetings held between 2002 to 2005. I participated in a number of those meetings as well as in workshops at the NQAPIA conference in Seattle last August, and I am very hopeful that NQAPIA will help us establish a firm foundation for a queer API presence nationally that we have not had until its founding.

But there are challenges facing queer API organizations, whether student, local or national, not the least being the struggle to fund their activities. Most local groups are entirely volunteer-run, and most are not even incorporated under state law, let alone tax-exempt 501(c)(3)s under federal law. Three distinct challenges that every queer API organization faces are these: the challenges of gender, ethnicity, and purpose.

First challenge: gender. Most local groups have until recently been either gay men’s organizations or lesbian organizations. To some extent, the binary gendering of our organizations may reflect our highly gendered cultures of origin in Asia and the Pacific region; such gendering may also reflect the legitimate concern of API women to have safe spaces, and spaces not dominated by our gay menfolk. When we founded GAPIC — Gay Asians & Pacific Islanders of Chicago — in 1994-95, I was still gay male-identified, and all seven of the founding members were gay men, even if the name of the organization itself was gender-neutral. But having subsequently transitioned and come out as a transgendered woman, I find such gendering offers both a challenge to define my place in such organizations. If there are no co-gendered or multi-gender groups in town, do I join the local men’s group or the local women’s group? But the flip side of the challenge is an opportunity to participate in differently gendered spaces. GAPIMNY was the first group of any kind that I joined when I moved to New York in 1995, but I have since also joined Q-Wave as well. When I was on the GAPIMNY steering committee, I proposed that the group amend its bylaws and mission statement to include transgendered men and women as well as gay, bisexual and questioning men, and the steering committee adopted that proposal. Q-Wave has been open to transgendered men and women as well as lesbians and bisexual and questioning women from the beginning, and I have facilitated or co-facilitated workshops on transgender issues for both GAPIMNY and Q-Wave. Clearly, at the national level, an organization such as NQAPIA has to be multi-gendered to be effective in representing the full diversity of our community simply in gender terms, but those questions of gendered space will not go away simply because of a stated intent to do so.

Second challenge: ethnicity. When we co-founded Iban/Queer Koreans of New York in 1997, it was out of an express desire to provide a Korean-specific space, though that group was multi-gendered from the beginning. Iban/QKNY was also in a curious sense multicultural, in that it attracted ethnic Koreans from Korea — primarily Korean-speaking first-generation immigrants and international students — as well as English-speaking Korean Americans and Korean adoptees. The very diversity of the group posed a challenge even for the conduct of our meetings. Even despite a commitment to completely bilingual meetings, conducting meetings with simultaneous interpretation from Korean to English and vice-versa meant that in practice, they veered from being primarily Korean-language to English-language and back again. Even beyond language, the needs and interests of the Koreans were in general quite different from those of the Korean Americans and Korean adoptees. Then, too, Iban/QKNY’s relationship to GAPIMNY also posed questions for both organizations (Q-Wave had not yet been founded in this period, 1997-99). Were GAPIMNY and Iban/QKNY brother or sister organizations or competitors? Questions such as these may also face LGBT/queer South Asian groups in their relations with pan-API groups.

Third challenge: mission, purpose and scope. Every queer API group has to answer this question: is its primary mission social? support? or political? or a combination of the three? Every group I’ve been a member of — including GAPIC, GAPIMNY, Q-Wave, and Iban/QKNY — has faced the challenge of responding to that question, and each has answered it slightly differently. The core activity of local queer APIs such as these is what is usually called the GM — the general meeting. The format is usually ‘educational’ in some sense, a workshop on coming out, on safer sex practices, or possibly on transgender identity or political activism. I recently participated with three others in facilitating discussion at a Q-Wave general meeting on religion and spirituality in the queer API community.

The challenge for queer queer API groups such as these is to serve those who are just coming out or not yet come out and at the same time retain the interest of those who are far more established in their queer identity and possibly more politically inclined. Social or political? Local queer API groups struggle to balance monthly potlucks or brunches that appeal to the socially-minded with activism and advocacy work that at least a few members seek to make a significant focus of those organizations. Being an activist, I would of course like to see queer API groups everywhere devote at least some of their energies to participation in what we may call the queer API movement. But my experience with every queer API organization from GAPIC onwards makes me cognizant of the importance of building group cohesion through social and support activities. The year that we spent in preparing for GAPIC’s first public event — a public forum on queer API identity and activism — was productive, but our organizing was incomplete, as we failed to consider the need to build a foundation for the organization through membership-building activities, which must of necessity include a strong social component.

So launching — or re-launching — a queer API movement cannot successfully be premised on a false and artificial distinction between the social and the political; the two must instead be conceived of as being mutually supporting, even if there is inevitably tension between them. Along with sufficient funding, the social cohesion of our local queer API groups are of necessity a crucial component of the launching pad for any successful and effective political movement.

Another component must be work through the media — both the mainstream media and the ethnic media, especially Asian-language print and broadcast media outlets. For all the good work that the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) does in monitoring English-language media in the United States, given the huge budget that the organization operates on — enormous by the standards of queer API organizations in this country — it is a matter of some disappointment to me that our leading national LGBT media organization (still) has no department that monitors Asian-language media both here and in Asia itself. Without a culturally competent GLAAD, our community is left with intermittent and scattershot attempts to monitor Asian-language media, which play such an important role in shaping Asian and Asian American perceptions of queer APIs.

In addition to media monitoring and the education of the public through existing media, we need to create media outlets of our own. Here, even the newsletters of local queer API groups can play a role, especially those that are digitized and uploaded to organizational websites and thus available to a far wider audience than such newsletters could have reached in the pre-Internet age. We as queer APIs must also increase LGBT participation in the Asian American Journalists Association (AAJA) as well as on the staffs of Asian American ethnic media outlets.

And of course, we must begin to elect queer APIs to public office, while at the same time being aware of the ever-present possibility that those elected from our community may succumb to the temptation of using identity politics to advance a self-interested political agenda that does not serve but may in fact undermine the community’s agenda of empowerment. The larger need is for participation in the political process, not merely to increase the representation of queer APIs in public office, but to advance an agenda of social justice and social change.

Student Activism: Academics & Alumni

Since this is a student conference and we are on a university campus, I would like to address one important component of any queer API movement, and that is student activism. If there are any students here who think there is little that they can do to participate actively in anything called a ‘movement,’ then they are laboring under a misconception. Let me point out three ways that students can do so.

First, queer API students can participate in student organizations, to ‘Asianize’ the LGBT student groups — which are often predominantly white — and to ‘queer’ the Asian American organizations on campus, which on some campuses may be overwhelmingly non-LGBT. From what I hear, some Asian American student organizations are little more than glorified straight dating sites. So if your college KSA or CSA or PSA isn’t doing much more than providing future marriage mates for the straight set, why not challenge them to do something really queer? Non-API or LGBT organizations can also provide opportunities for activism, including your on-campus chapter of Amnesty International or other human rights organizations, for example.

Second, there is the academic side, with Asian and Asian American studies programs and departments just ripe for the queering, not to mention the opportunities to ‘Asianize’ the LGBT studies or queer theory program at your school. If the AAS program on campus isn’t doing anything queer, propose something; same for LGBT studies programs that have no courses on queer APIs.

Third, follow the money. Students may often feel powerless, especially on large university campuses with distant administrators running the show. I wonder whether senior administrators sometimes are influenced by the model minority myth in making decisions on resources available to people of color, afraid that African American and Latino students may act up if they do not get adequate resources but complacent about API students because they think that APIs will not agitate. It took years of agitation for the University of Illinois to build the APA Cultural Center, which now shares the same building as the AAS program. If the opinions of students are often blithely disregarded by senior administrators at many colleges and universities, those of alumni cannot be, because alumni are usually the single largest group of regular donors to their alma maters. But instead of giving to the college- or university-wide alumni association, why not start an API or LGBT alumni association or even a queer API alumni association? An alumni association run by queer API alumni that is independent of the college or university can create an endowment that can fund queer API-specific programs and projects.

In short, there is so much that you can do to help create a queer API movement even before you graduate, and even more once you do. There are many significant and even daunting challenges, including the ones that I have mentioned here. But don’t be afraid to think big. The goal of a queer API movement must be nothing less than the transformation of society — our own as well as the societies of our communities and cultures of origin — so that all of us of Asian or Pacific Islander descent who identify with the L, G, B and/or T can reclaim our rightful place in those communities and participate actively in the articulation of the governing narratives that shape our life chances and opportunities as human beings.

Thank you.

One thought on “Articulating Identity, Organizing Community: Re-Launching the Queer API Movement”

Thank you, Pauline, for this amazing speech. I wish I could have been there to listen to you speak! So much of what you said is particularly relevant to the queer API space that I am involved with; as a member of Cal Q&A and someone who is hoping to get more involved in the space, I have been thinking about the balance between the political, the support, and the social. I know that as a Q&A space, it is inherently all three of those things, both because of why it was established and how those qualities are innately embodied in the Q&A identity. Just the statement that there needs to be a space for the often quieted and forgotten queer API voice – that it exists in the first place – says so much about why the intersection of those identities need to be represented.

At the same time, I had to think about what Q&A, as a college organization, is for? I see QACon as political, social, and support at the same time; it’s a political statement of presence, a time for a hidden community to get to know itself, and a place for people to build a collective strength. Q&A has been all of those things, and the balance between the three is extremely delicate. So how can we, say, launch the space into something that is bigger than it is right now? And do we even want to do so?

I also am pleased to learn more and more about the queer API past every single day. It would be a powerful message to send out to misinformed API people – that the API heritage is rich with queer history and content. Actually, it could be a message to so much more than those of Asian identity; one way to really put ourselves out there in the LGBT sphere would be to affirm the role that the queer has had in our history.