Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg signed Int. No. 24 into law on 30 April 2002, with lead sponsor Council Member Bill Perkins and the coordinator of the legislative work group Pauline Park at his side; Ariel Herrera, Christine Quinn and Joe Grabarz stand to her left.

NYAGRA history: 2002

The year 2002 represents a key turning point in the history of the New York Association for Gender Rights Advocacy (NYAGRA), a year in which the organization was convulsed by its greatest crisis, a drama which broke out into full public view over the course of the spring and summer. Ironically enough, 2002 was also a year in which NYAGRA would lead a legislative campaign to its successful conclusion, putting the organization on the national map as an effective force in the legislative arena. As in life, so in organizational life: triumph mixed with tragedy; or, to put it somewhat more dramatically, tragedy that threatened to undermine NYAGRA just at the very moment of our greatest organizational triumph.

The backdrop to the NYAGRA crisis was the struggle over the issue of transgender inclusion in the Sexual Orientation Non-Discrimination Act (SONDA). In June 2001, the bill seemed to be moving forward, after many years in which it had passed the New York State Assembly but had been declared dead on arrival in the Senate. Charles King, executive director of Housing Works, which by this point housed NYAGRA and its paid staff, approached me early in the summer of 2001 about a plan to lobby the state legislature on transgender inclusion in SONDA.

Charles King insisted that NYAGRA, as the only statewide transgender advocacy organization, could block SONDA if the organization joined Housing Works in lobbying the lead sponsors in the Assembly and the Senate. In response, I told Charles that a decision of such importance was for the board of directors to make, not for me alone, but that NYAGRA had always been focused on gaining legal rights for transgendered and gender-variant people, not denying rights to non-transgendered lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) people. I also pointed out that NYAGRA, as a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit corporation, NYAGRA was limited in its ability to lobby on pending legislation, to which Charles responded that such restrictions would not preclude the organization from joining Housing Works and the Empire State Pride Agenda in sponsoring a one-day conference in Albany. At the meeting of an ad hoc coalition on SONDA that summer, Matt Foreman, then-executive director of ESPA, had offered to help organize just such a conference, and Charles King had countered by offering $5,000 if ESPA would offer $5,000 and NYAGRA would put up $10,000.

Given that NYAGRA had only very recently received a $50,000 grant, and that our current grant income was only around $70,000, and even that funding not purposed for underwriting such a conference, it seemed to me foolish at best to spend a full one-seventh of our income on a one-day conference, even if we could persuade our funders to approve the use of that funding to organize such a conference.

At our board retreat in August, I raised the issue with board members, who agreed with me and voted unanimously to reject Charles King’s proposal; at that meeting, Jamie Hunter, as our one paid staff member, took notes on a laptop, notes which documented the unanimous board vote rejecting the Housing Works proposal:

“…Motion that we graciously decline Charles’ offer. Passed unanimous…”

In addition to agreeing with me that the expenditure of $10,000 on a one-day conference was imprudent, my board colleagues also agreed that the position of NYAGRA on SONDA must be that we could not support the bill because it was not transgender-inclusion but that we would not oppose it, because we supported rights for non-transgendered LGB people.

Over the course of the next four months, David Valentine, Hawk Stone, and I — as the three members of the human resources and administration committee (HRAC) — came to consensus that Jamie Hunter had proved ineffective as a paid staff member, and that if her performance did not improve within a relatively short period of time, that we would need to terminate her, and I communicated that consensus to Jamie in December 2001.

In January 2002, NYAGRA held one of its relatively rare in-person board meetings, with all members present, as well as two of the three board member candidates. Andrea Sears, Liz Loeb, and Cynthia Kern had been elected to positions created at the August 2001 board retreat as non-voting members of the board who were candidates for full membership. However, at the time of their election to board candidacy, neither Andrea nor Jamie had divulged the fact that they were involved with each other in a primary relationship, a potential conflict of interest, given that Andrea, as a board member, would be in a position of general supervisory responsibility over her lover, even if Andrea was not a member of the committee that directly supervised Jamie. The conscious decision to keep from the board their relationship and the potential conflict of interest that Andrea’s election to the board would create was only one of many serious instances of dishonesty on the part of both Andrea and Jamie that would mount over the course of the year.

In any case, the January board meeting proved to be among our most important discussions as a board, as we carefully considered (reconsidered, in fact), the SONDA situation and NYAGRA’s position on the legislation. At the meeting, Jamie mentioned that Sylvia Rivera was organizing a demonstration at ESPA headquarters on Hudson Street in the West Village to protest the continued exclusion of transgendered people from SONDA, and she and Andrea aggressively promoted the ostensible value of NYAGRA’s participation in the event. I argued that NYAGRA was still a relatively small and new organization and that much of our support came from non-transgendered LGB people, at least some of whom might not understand our taking a position that could be interpreted as opposition to their rights. I also pointed out that there was no realistic chance of SONDA being amended to include gender identity and expression before its passage in the Senate, as the lead sponsor in the Assembly (Steve Sanders) had already indicated that he would not amend the bill without the express approval of the Pride Agenda (approval which was most decidedly not forthcoming), but that passage of Int. No. 24 — the transgender rights bill pending in the New York City Council — was virtually assured now that we had a new Speaker who was one of the co-sponsors of the bill. Alienating ESPA over SONDA at the expense of Intro 24 would be, in effect, to risk throwing away the near certainty of a local transgender rights law for the sheer gratification of defying the Pride Agenda.

Over the loud objections of Jamie and Andrea, I proposed that the board vote to reaffirm our position of neutrality on SONDA and to decline participation in the demonstration against ESPA. Neither Andrea nor Liz could vote, and Cynthia was not present, but all of the full members of the board voted in favor of my proposal, in the presence of both Andrea and Jamie. As a member of the NYAGRA staff, Jamie was under the direction of the board and bound to respect an explicit and unanimous vote of the board of directors; and so it was with astonishment that I found an advertisement for the anti-ESPA demonstration in Gay City News that Saturday that included NYAGRA’s name as one of the organizational sponsors.

It was absolutely clear to me that NYAGRA’s name could not have been included in that list without Jamie, but when I confronted her in a phone call, she denied having any knowledge of the inclusion of NYAGRA’s name in the ad, instead insisting that it was Sylvia Rivera who had made the decision to include NYAGRA’s name in the ad. But when I asked for a phone number for Sylvia so that I could speak to her about it, Jamie told me that Sylvia was in the hospital and was unreachable; it was apparent to me at the time that that excuse was a subterfuge, and Paul Schindler, the editor of Gay City News, would later confirm in a phone call that Jamie had placed the ad, just as I had suspected; Sylvia may have paid for the ad, but had had no involvement with its construction or placement, Paul told me. But to cover her tracks, Jamie told me that all contact with Sylvia had to go through Rusty Mae Moore; when I asked if I could speak with Rusty, Jamie told me that Rusty, too, was unreachable.

I had always treated Jamie with the greatest respect, and my two phone conversations with her that Sunday and Monday were the only occasions on which I had even raised my voice; but it was clear to me that Jamie was lying to me and that she had directly contravened the express will of the board of directors, working to undermine NYAGRA’s position on SONDA, even though she had been at the August 2001 board retreat at which we had initially voted in favor of that position and at the January board meeting at which we had voted unanimously to reaffirm it. Such an action by a paid staff member in direct defiance of the explicit will of the board of directors would be considered a terminable offense by any board in any organization.

By this point, Jamie’s attempt to deceive me as to the placement of the ad in GCN had raised my suspicions, and when I stopped by the Housing Works office on W. 13th St. where NYAGRA had a desk, I decided to check the documents and e-mail on the NYAGRA computer. Given the legal disputes that were soon to ensue, it is important to point out that the computer was the NYAGRA computer, not Jamie’s personal property nor that of Housing Works. And as a NYAGRA employee, Jamie had no reasonable expectation of privacy regarding anything on the NYAGRA computer, her claims to the contrary notwithstanding. Furthermore, Jamie knew that I used the computer frequently when I came into the Housing Works office, so it should have been no surprise to her that I would turn it on when I came in that Tuesday afternoon. When I turned on the computer, I discovered e-mail messages and Microsoft Word documents that clearly implicated Jamie in what can only be termed a conspiracy to undermine NYAGRA and its organizational position on the pending SONDA bill.

Among those documents was a flyer to be distributed by fax announcing the anti-ESPA demonstration which only Jamie could have put on the computer, along with a host of e-mail messages going as far back as September documenting her complicity in Charles King’s plot to undermine SONDA and ESPA. Upon reading the documents and the e-mail messages, it became clear to me that Charles had refused to take ‘no’ for an answer, and after communicating to him the NYAGRA board’s unanimous decision to decline his proposal for NYAGRA involvement in an effort to lobby against SONDA, Charles had enlisted Jamie’s participation in that effort. In effect, Charles had turned Jamie into a Housing Works employee, even while she was still being paid by NYAGRA grant funding — grant contracts that explicitly prohibited lobbying on pending legislation. Charles had enticed Jamie into a political relationship whose objective to lobby against SONDA’s passage was in direct contravention of the express will of the NYAGRA board of directors — clearly communicated to both Charles and to Jamie — as well as in contravention of 501(c)(3) law and the terms of our grant contracts. Jamie was risking NYAGRA’s 501(c)(3) status in order to advance an agenda in direct opposition to the organization’s position, something that no board of directors of any 501(c)(3) could or would tolerate. Outrageously, Jamie would attempt to use my discovery of her betrayal of the NYAGRA board and of the organization to oust me from the board of directors.

After the discovery of Jamie’s illicit activities, I immediately called Hawk Stone and Stuart Chen-Hayes, the two members of the board whose advice and counsel I thought would be most useful in such a dangerous situation. Both were shocked and both made it clear that they considered Jamie’s activities a terminable offense. Hawk urged me to remove the computer from Housing Works in order to prevent Jamie or Charles from destroying the evidence of the conspiracy. I went home that evening extremely disheartened and called David Carter, an old friend of mine who lived in Greenwich Village, not far from the Housing Works office. I told David of Hawk’s advice. David did not attempt to sway me one way or the other, but he did offer to keep the NYAGRA computer at his apartment if I should decide to remove it from Housing Works. And so, the next day, I went into the office on W. 13th St. and unplugged the computer after printing out a few documents, carefully placed the tower in a large shopping bag, and carried it out the door, hailing a taxi to take me to David’s apartment, where I stored it for the time being. On Hawk’s advice, I left a short hand-written note telling Jamie that I had taken the computer in for repair and that I would be bringing it back to Housing Works as soon as it was repaired.

When Jamie discovered the note and found the computer missing, she must have gone into a panic, realizing that I now had all of the evidence that I needed to seek her termination, should I wish to do so. Significantly, Jamie immediately went to Donna Cartwright, a founding board member with whom I had a rather ambivalent relationship. It had become apparent to me that Donna was jealous of me, envious of the position of public prominence that I had attained as an activist since leading the campaign for Int. No. 24 — despite the fact that she had rejected my entreaties to take up the position of coordinator of that campaign. After Jamie told Donna about the computer, they went to Charles King, who then issued a directive banning me from the premises and ordering me to return the computer immediately — despite the fact that he, as executive director of Housing Works, had no authority over me or Jamie, much less any claim on the computer, which was NYAGRA property.

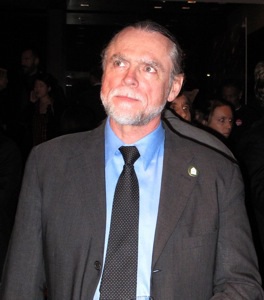

Charles King, then executive director of Housing Works (now CEO)

Charles King, then executive director of Housing Works (now CEO)

The directive ordered me banned not only from the Housing Works office on W. 13th St. where NYAGRA had a desk and a mail box, but also from all Housing Works property throughout the city, including offices, bookstores and thrift stores. Branding me a banned person was a conscious attempt on Charles King’s part to undermine my supervisory role, as it would seriously reduce my ability to supervise Jamie’s work, assuming that she was doing any legitimate work for NYAGRA.

At the bill signing ceremony for Int. No. 24 on 30 April 2002, Melissa Sklarz, Council Member Margarita Lopez, Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, Commissioner Patricia Gatling (front row); Diana Montford, Jamie Hunter, Andrea Sears, Pauline Park, Council Member Bill Perkins, Council Member Helen Sears, Council Member Bill de Blasio, Council Member Christine Quinn, Joe Grabarz of the Empire State Pride Agenda, and Mark Newman (counsel to the General Welfare Committee).

At the bill signing ceremony for Int. No. 24 on 30 April 2002, Melissa Sklarz, Council Member Margarita Lopez, Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, Commissioner Patricia Gatling (front row); Diana Montford, Jamie Hunter, Andrea Sears, Pauline Park, Council Member Bill Perkins, Council Member Helen Sears, Council Member Bill de Blasio, Council Member Christine Quinn, Joe Grabarz of the Empire State Pride Agenda, and Mark Newman (counsel to the General Welfare Committee).