Tolkien & “The Silmarillion”: cultural influences & mythopoeia in the shaping of an epic

by Pauline Park

“The Silmarillion” is J.R.R. Tolkien’s longest work and arguably his most complex; it is the work that took Tolkien the longest to write and remained unfinished at the time of his death, to be put together as a single volume by his son Christopher Tolkien. “The Sil” (as some Tolkien fans refer to it fondly and casually) also covers an enormous amount of time in Middle Earth years.

As with any great work of literature, “The Silmarillion” reflects many different cultural influences. I see Hebrew/Judaic, Greek and Germanic influences in different parts of this sprawling work, with the Germanic influences predominating; let me begin with what I see as the secondary influences.

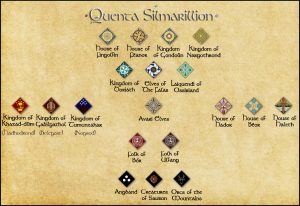

As noted above, Christopher Tolkien pulled together “The Silmarillion” after his father’s death, bringing into one published volume what were really multiple manuscripts at various stages of completion. The table of contents in the published version of 1977 begins with the “Ainulindalë,” follows with the “Valaquenta” (the “Quenta Silmarillion”), and concludes with the “Akallabêth,” followed by the codocil, “Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age,” basically a summary of “The Lord of the Rings,” Tolkien’s most popular work and masterpiece.

The “Ainulindalë” is Tolkien’s Book of Genesis in which he tells the story of the creation of Middle Earth and it is the one part of the “Sil” that reflects Judaic cultural influence insofar as it is Tolkien’s rewriting of the Hebrew Old Testament’s first book. The most specifically Judaic element is the role of Ilúvatar as the supreme being, even if in some ways the pantheon of deities introduced in the “Ainulindalë” is also reminiscent of the pantheon of Greek and Roman gods and goddesses. Perhaps the most specifically Judaic (or more broadly ‘Judeo-Christian’) element here is the figure of Melkor; referred to as ‘Morgoth’ through most of “The Silmarillion,” he is the ‘Satan’ figure, the fallen angel who challenges the authority and power of Ilúvatar and the other Valar (gods), in a narrative told with some of the most exquisite language in any of Tolkien’s writings.

At the tail end of the published volume is “The Akallabêth,” which is Tolkien’s Atlantis story and which in that regard reflects Greek influence more so than any other part of the “Sil.” Reading the “Sil” for the first time, I was struck by the name of the last king of Númenór: whether Tolkien had this in mind, ‘Ar-Pharazôn’ sounds to me redolent of the title ‘pharaoh,’ with the hint of the Egyptian captivity of the ancient Israelites. The story of the downfall of Númenór ends the grand narrative of “The Silmarillion” insofar as “Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age” is little more than an artful summary of the plot of “The Lord of the Rings.”

But “The Silmarillion” proper is the “Valaquenta” or “Quenta Silmarillion,” which runs from page 25 to page 255 of the edition published by Houghton Mifflin in 1977 — in other words, the bulk of the text— and here the predominant influence is undoubtedly Germanic. In writing this difficult and complex work, Tolkien drew upon decades of reading of Old English, Old Norse and other Germanic language texts, among them “Beowulf,” the greatest of all Anglo-Saxon epic poems. Tolkien was also strongly influenced by his reading of the Old Norse sagas, two of which (“Njal’s Saga” and “Egil’s Saga”) I have read myself. It is also quite possible and indeed probable that Tolkien was familiar with the greatest battle poem in English, describing the Battle of Maldon in Essex in 991 which includes perhaps the single most famous line in Old English poetry:

5) light vs. darkness

Last but not least, it is important to note the theme of ‘light vs. darkness’ that is central to “The Silmarillion,” which begins with the story of the creation of the world in the “Ainulindalë,” on page 19 of which Tolkien specifically and explicitly references ‘Darkness,’ which Tolkien says the Ainur “had not known before except in thought” before that moment. In chapter seven, Tolkien tells the story of Fëanor’s creation of the Silmarils, which capture “the light of the Trees, the glory of the Blessed Realm” (p. 67); in that sense, the long struggle between and among various parties including his sons to capture and recover these precious jewels is in fact a struggle over and between light and darkness. Of course notions of light and darkness are hardly unique to Germanic literature and are to be found in the literature of every society and culture; but Tolkien was almost certainly influenced by specifically Germanic cultural references to light and darkness in shaping the narrative of “The Silmarillion.” One of Tolkien’s favorite works, “Beowulf” is shot through with such references, as in line 1136 in which the anonymous author of the Anglo-Saxon epic refers to ‘the wonder of light’ (sēle bewitiað). In lines 1963-1966, the poet declaims, “Heroic Beowulf and his band of men crossed the wide strand, striding along the sandy foreshore; the sun shone, the world’s candle warmed them…”(Gewāt him ðā se hearda mid his hond-scole sylf æfter sande sǣ-wong tredan, wīde waroðas; woruld-candel scān, sigel sūðan fūs) (translation, Seamus Heaney). The great spider Ungoliant is a particularly interesting example of darkness in “The Silmarillion,” an awful creature who “hungered for light and hated it” (p. 73); she ”sucked up all the light that she could find, and spun it forth again in dark nets of strangling gloom…”