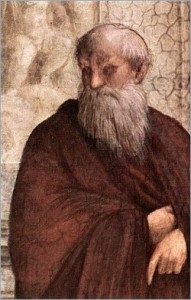

Plotinus, as depicted by Raphael in “The School of Athens”

Plotinus on the soul:

The souls of men, seeing their images in the mirror of Dionysus as it were, have entered into that realm in a leap downward from the Supreme: yet even they are not cut off from their origin, from the divine Intellect; it is not that they have come bringing the Intellectual Principle down in their fall; it is that though they have descended even to earth, yet their higher part holds for ever above the heavens.

Their initial descent is deepened since that mid-part of theirs is compelled to labour in care of the care-needing thing into which they have entered. But Zeus, the father, takes pity on their toils and makes the bonds in which they labour soluble by death and gives respite in due time, freeing them from the body, that they too may come to dwell there where the Universal Soul, unconcerned with earthly needs, has ever dwelt…

We may know this also by the concordance of the Souls with the ordered scheme of the kosmos; they are not independent, but, by their descent, they have put themselves in contact, and they stand henceforth in harmonious association with kosmic circuit — to the extent that their fortunes, their life experiences, their choosing and refusing, are announced by the patterns of the stars — and out of this concordance rises as it were one musical utterance: the music, the harmony, by which all is described is the best witness to this truth. Such a consonance can have been procured in one only way: The All must, in every detail of act and experience, be an expression of the Supreme…

(from the Fourth Ennead, Third Tractate, written 250 C.E. and translated by Stephen Mackenna and B. S. Page).

Let every soul recall, then, at the outset the truth that soul is the author of all living things, that it has breathed the life into them all, whatever is nourished by earth and sea, all the creatures of the air, the divine stars in the sky; it is the maker of the sun; itself formed and ordered this vast heaven and conducts all that rhythmic motion; and it is a principle distinct from all these to which it gives law andmovement and life, and it must of necessity be more honourable than they, for they gather or dissolve as soul brings them life or abandons them, but soul, since it never can abandon itself, is of eternal being.

How life was purveyed to the universe of things and to the separate beings in it may be thus conceived: That great soul must stand pictured before another soul, one not mean, a soul that has become worthy to look, emancipate from the lure, from all that binds its fellows in bewitchment, holding itself in quietude. Let not merely the enveloping body be at peace, body’s turmoil stilled, but all that lies around, earth at peace, and sea at peace, and air and the very heavens. Into that heaven, all at rest, let the great soul be conceived to roll inward at every point, penetrating, permeating, from all sides pouring in its light. As the rays of the sun throwing their brilliance upon a lowering cloud make it gleam all gold, so the soul entering the material expanse of the heavens has given life, has given immortality: what was abject it has lifted up; and the heavenly system, moved now in endless motion by the soul that leads it in wisdom, has become a living and a blessed thing; the soul domiciled within, it takes worth where, before the soul, it was stark body- clay and water- or, rather, the blankness of Matter, the absence of Being, and, as an author says, “the execration of the Gods…”

By the power of the soul the manifold and diverse heavenly system is a unit: through soul this universe is a God: and the sun is a God because it is ensouled; so too the stars: and whatsoever we ourselves may be, it is all in virtue of soul; for “dead is viler than dung…”

This, by which the gods are divine, must be the oldest God of them all: and our own soul is of that same Ideal nature, so that to consider it, purified, freed from all accruement, is to recognise in ourselves that same value which we have found soul to be, honourable above all that is bodily. For what is body but earth, and, taking fire itself, what [but soul] is its burning power? So it is with all the compounds of earth and fire, even with water and air added to them…?

The Soul once seen to be thus precious, thus divine, you may hold the faith that by its possession you are already nearing God: in the strength of this power make upwards towards Him: at no great distance you must attain: there is not much between…

(from the Fifth Ennead, First Tractate, written 250 C.E. and translated by Stephen Mackenna and B. S. Page).