Invisible No More

By John Caldwell

The Advocate

15 March 2005

It’s been a year since an offensive feature in Details inspired unprecedented activism and visibility among gay and lesbian Asians. So how much has really changed?

While Andy Wong has gotten over what he calls “the biggest mistake of my life”—joining the Mormon Church in high school—he still struggles with being gay in his traditional Chinese immigrant family. Now living in San Francisco, the 24-year-old activist grew up in a conservative neighborhood in San Diego. When he came out at 18, he says, his mother at first accepted his homosexuality, then backed away. “She desperately wants me to have children and has mentioned more than a few times that she wished I would turn temporarily straight so that I could conceive a grandchild for her,” he says.

Filmmaker Quentin Lee, who grew up in Hong Kong before immigrating to Montreal, has faced his own demons. “Long Duk Dong traumatized my entire generation of Asian males,” says the 34-year-old, referring to Gedde Watanabe’s extreme Asian stereotype in the 1984 John Hughes comedy Sixteen Candles. Twenty years later, young gay Asians looking for people like themselves still have few choices, Lee notes: “Asian men are often left out of popular culture, and gay Asian men are nonexistent.”

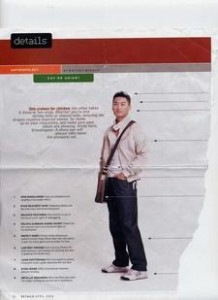

That invisibility is one reason both gay and straight Asians were outraged by Details magazine’s “Gay or Asian?” stab at humor. When Wong first saw that April 2004 feature he was offended but not surprised by the sarcastically captioned photograph of a young, spiky-haired Asian man dressed in metallic shoes and a V-neck T-shirt. Portrayals of Asian men as sexually ambiguous or purely feminine are still quite common, he says: “This is an issue that the gay Asian community has faced time and time again. There’s so much ignorance.”

Nearing the one-year anniversary of the Details article, Wong says little has changed for gay Asian people. Yes, studies have been done and pro-Asian programs implemented, “but there’s still a lot of work to be done. We need to really speak out on our own invisibility.”

Glenn Magpantay, cochair of Gay Asian and Pacific Islander Men of New York and a staff attorney with the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund, agrees. He helped organize a high-profile protest outside the Details office in Manhattan that resulted in a full-page apology from the magazine. “[But] we are still finding homophobic articles in the Asian-language press and anti-Asian caricatures in the gay media,” he says.

The Details controversy did shed light on the pervasive stereotypes and general lack of positive representation that Asian men continue to face. Despite the success of gay Asian stars like Alec Mapa and B.D. Wong, “gay Asian men are still not perceived to be popular,” says Lee, who has featured young gay Asian characters in his independent films Drift and Ethan Mao.

Gay Asians are still perceived as passive or exotic, says Alain Dang, 28, a gay Asian activist in Manhattan and a member of the New York API group. “The Details article really perpetuated the ‘rice queen’ phenomenon,” he says, referring to gay men who pursue Asian lovers on the assumption they’ll be passive or submissive. “It’s a real part of my existence and my friends’ existence. It’s been hard.”

That particular assumption crosses gender lines, says Pauline Park, a transgender Asian activist in New York. “I actually have had men say, ‘I really like Asian women because white women can be too independent,’” Park says. “One of the big challenges for transgender Asian women, just like gay Asian men, is dealing with our exotification by men of all races. The assumption is that you’re going to be submissive. I’m not. It’s annoying and dispiriting to have to constantly correct assumptions.”

This battle against expectations is also something many gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender Asian people face within their ethnic groups. There’s racism in the gay community,” Park says. “But there’s a bigger problem of homophobia in the Asian–Pacific Islander community.” Cultural traditions of marriage and child rearing often make it difficult for gay Asian men to come out, says Dang, who was born and raised in Cupertino, Calif., amid a large and traditional Asian family. “All my parents want are grandchildren,” he says. “At every family event I’m accosted by relatives asking me if I have a girlfriend.”

Dang, who works as a policy analyst for the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, isn’t out to any of them. “It’s something I struggle with because I’m completely out socially and professionally,” he says. “Deep down I know that they love me regardless and nothing could break that bond; I’m just dreading the actual conversation.”

Hoping to help people like his family members understand, Wong, who is director of development at Community United Against Violence, a gay advocacy group in San Francisco, started a first-of-its-kind national organization dedicated to raising awareness about gay issues in the larger Asian population. When over 7,000 Asian-Americans rallied against same-sex marriage in San Francisco last April, Wong was inspired to form the gay rights group Asian Equality, which he now heads. He organized his own San Francisco rally in August and in February helped put together the first marriage equality float for the San Francisco Chinese New Year Parade. “Over 3 million Chinese-Americans saw it,” Wong says. “This was a unique opportunity to present a powerful message and to have loving same-sex Asian couples standing side by side.”

Patrick Mangto, who was executive director of Asian Pacific Islanders for Human Rights in Los Angeles until March 1, says in the past year his group has been making inroads through efforts to publish pro-gay ads in Asian community newspapers. Many initially resisted, fearing readers’ reactions, but the ads are now reaching more and more Asian-Americans. “Most of our ads are run in native languages so that it’s not an outside thing,” Mangto says.

The Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation has also been working with the media to ensure that there are positive depictions of gay Asians, notes Andy Marra, Asian–Pacific Islander media fellow for the group [see page 10], while the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force in February released an unprecedented study coauthored by Dang that looks at the challenges gay Asian families face.

But support from such mainstream gay rights groups is still limited, Wong says. A recent unity statement from 22 gay rights groups didn’t include a single signature from a gay Asian organization. “Asian-Americans are chief plaintiffs in lawsuits to win same-sex marriage, yet we weren’t even asked to sign on to this statement,” Wong notes. “This was an opportunity for them to reach out to us.”

It’s true that gay Asian groups and activists have been left out in the past, Marra says, but she’s optimistic. “It’s amazing that our issues are even being discussed and being brought to the table,” she says. “We are seeing an emerging movement.”

This article originally appeared in the 15 March 2005 of The Advocate magazine, which is now defunct.