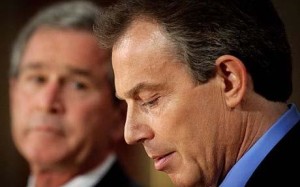

Is Tony Blair spun out?

Living, and dying, by spin.

By Pauline Park

SEPTEMBER 5, 2003. “Prime Minister, do you have blood on your hands? Are you going to resign?” Those were the shocking questions posed by a British journalist to Tony Blair at his press conference in Tokyo with Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi on July 19. The media had just reported the death of Dr. David Kelly, the weapons expert who had raised doubts about British government claims justifying war in Iraq, namely that Saddam Hussein posed an immediate threat to the security of the United Kingdom as well as the United States.

The questions left Blair shaken and literally speechless for the first time in his premiership, a remarkable moment for someone who is arguably the most media-savvy British Prime Minister in history. His Japanese counterpart rescued him by grabbing his arm and leading him out of the press room.

The questions linger, however. They are now being asked in more polite language by Lord Hutton, the law lord (one of 12 judges of Britain’s final court of appeals) who is leading an independent government inquiry into the death of the weapons expert. The Hutton inquiry is being decried by critics as too narrowly focused on the minutae surrounding the apparent suicide of the man the government now acknowledges was its top expert on Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction, a sentimental sideshow that skirts the main issue: whether or not Blair took his nation to war in Iraq under false pretences. Nevertheless, whatever conclusions Lord Hutton ultimately reaches in his final report, the Kelly affair has already shaken Blair’s Labor government to its foundations.

The Kelly affair has not only undercut the Blair government’s rationale for war in Iraq, but has gone right to the heart of its foreign policy, which is premised on the ‘special relationship’ with the United States. It has also raised questions about the nature of ‘cabinet government’ in Britain under an administration that has been presidentialized beyond all recognition, and has exposed the tenuous relationship between Tony Blair, a Clintonesque third way triangulator pursuing essentially conservative economic policies, and a Labor Party steeped in an ostensibly ‘socialist’ tradition. Most importantly, the Kelly affair has raised doubts about the character and credibility of Tony Blair himself.

Just how far Tony Blair has fallen can be seen in the latest batch of public opinion surveys. In late July, ten days after Dr. Kelly was discovered dead, the London-based MORI (Market & Opinion Research International) found that 49 percent of Britons polled thought Blair was untrustworthy, and 55 percent disapproved of his handling of the situation in Iraq, with only 32 approving.

The increasing disillusionment with the Prime Minister is now spreading into generalized disenchantment with his administration. Sixty percent of Britons surveyed by MORI in July declared themselves dissatisfied with Blair and 65 percent dissatisfied with the entire Labor government. For the first time since 1997, the Conservatives are ahead in some polls of voter intention in the next election. The widespread distrust of Blair, and even contempt for the Prime Minister, is in stark contrast with his election in 1997, when he was greeted as a liberating hero who had delivered Britain from the sleaze and scandal of the Tory years. Blair and his Labor government are now facing the greatest crisis since they came to power in 1997, and they have no one to blame but themselves.

At the heart of the matter is what Blair’s critics have called the ‘culture of spin,’ the aggressive and even obsessive attempt by the Prime Minister and his people to control media coverage of the government. Blair’s spinmeister was his top aide, Alastair Campbell, the director of communications at 10 Downing Street until his resignation last week. He was recently described in The Guardian as “the man who embodied the control freakery which took hold of the Labor Party after the disastrous general election defeat of 1992.”

It was Campbell’s obsession with controlling media coverage of the war in Iraq and its aftermath that led to the extraordinary row between the government and the BBC, the outing of Dr. Kelly as the primary source of Andrew Gilligan’s critical report for the BBC’s Today program, and arguably the tragedy of the weapons expert’s apparent suicide. Ultimately, Campbell’s obsession with media control led to his own fall from power, as the public came to see Dr. Kelly as the victim of the culture of spin that Blair and his top aide had helped create.

The extraordinary outcry in Britain over Dr. Kelly’s death is largely due to the fact that he has put a human face on the culture of spin. The dead weapons expert is viewed as something of a hero now in Britain, a good and decent man driven to despair by a heartless spinmeister who cared little for the very human consequences of 10 Downing Street’s obsession with media control. Upon hearing of Campbell’s resignation, Theresa May, the Tory chairwoman, predicted, “The departure of Tony Blair’s director of communications will not mean an end to the culture of spin and deceit at the heart of government.” Unfortunately for Blair, this may be more than just a partisan denunciation; there is the very clear prospect of it becoming a generally accepted assessment, even among Labor parliamentarians and Labor voters.

How much the deceit factor will hurt Blair and the Labor Party in the long run remains to be seen. The same late July MORI survey found 50 percent of Briton’s still supported their country’s participation in the Iraq war. At the end of June, Blair was still considered the most capable Prime Minister (35 percent of respondents), twice as much as his nearest rival in this category, Liberal Democrat chief Charles Kennedy. “To win general elections it is more important to be seen as capable than as honest, although honesty is desirable,” MORI analysts noted.

There is a point, however, when dishonesty, particularly when publicly unmasked, becomes indistinguishable in the public eye from incompetence. The Kelly scandal has brought the Blair government perilously close to that point. Campbell’s precipitous exit, 10 Downing Street’s promises to rein in the spin, and its support of the tightly limited Hutton inquiry are attempts to pull back from the edge.

The Blair government is perhaps the most disciplined machine of a political administration that Britain has ever seen, and that is saying quite a lot, given the tight ship that Margaret Thatcher ran for eleven years. But, a government cannot sustain itself indefinitely on spin, and media manipulation, in the absence of principle or a commitment to policy, particularly now that it is faced with the daily unraveling of Iraq and a British media avidly following the unpredictable scent of the Kelly scandal.

This article originally appeared on the website of The Gully on 3 September 2003.