15 Favorite Operas and 15 More: Reflections on the Love of a Lifetime

By Pauline Park

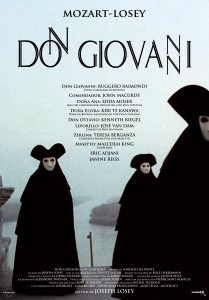

I have been listening to opera and attending opera performances since 1979, when I discovered this ‘exotic and irrational entertainment’ through an album of Mozart arias by Margaret Price and Joseph Losey’s film of “Don Giovanni.” Since then, I have seen hundreds of opera productions of everything from the old ‘war horses’ to what are referred to as operatic ‘rarities.’

Recently, it occurred to me that I should try to produce a list of favorite operas, and I have been struggling to come up with a list of ten operas that I could not live without, and that has proved more difficult a task than one might imagine. For one thing, ten is an extremely arbitrary number, albeit one that is the basis for contemporary life; the ‘modern’ would be impossible without decimalization. But ‘top ten’ lists proliferate in every area of human activity, and so, in keeping with that somewhat arbitrary but widely accepted standard, I have finally produced a list of my favorite 30 operas. The first 15 are those I simply couldn’t live without:

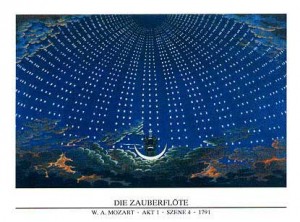

1) Die Zauberflöte (Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, 1791)

2) Così Fan Tutte (Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, 1790)

3) Don Giovanni (Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, 1787)

4) Le Nozze di Figaro (Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, 1786)

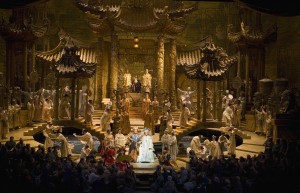

5) Turandot (Giacomo Puccini, 1926)

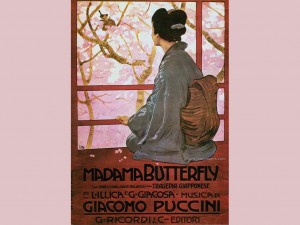

6) Madama Butterfly (Giacomo Puccini, 1904)

7) Falstaff (Giuseppe Verdi, 1893)

8) Giulio Cesare (George Frideric Handel, 1724)

9) Cavalleria rusticana (Pietro Mascagni, 1890)

10) Die Fledermaus (Johann Strauss II, 1874)

11) Der Freischütz (Carl Maria von Weber, 1821)

12) Manon (Jules Massenet, 1884)

13) La Cenerentola (Gioachino Rossini, 1817)

14) Don Carlos (Giuseppe Verdi, 1867)

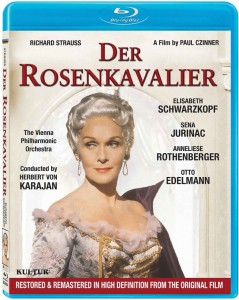

15) Der Rosenkavalier (Richard Strauss, 1911)

The next 15 are those I could live without but would prefer not to have to:

16) La Fanciulla del West (Giacomo Puccini, 1910)

17) Eugene Onegin (Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, 1879)

18) Hänsel und Gretel (Engelbert Humperdinck, 1893)

19) Il Barbiere di Siviglia (Gioachino Rossini, 1816)

20) Les Contes d’Hoffmann (Jacques Offenbach, 1881)

21) Ariadne auf Naxos (Richard Strauss, 1912)

22) Dido and Aeneas (Henry Purcell, 1683)

23) Götterdämmerung (Richard Wagner, 1876)*

24) Castor et Pollux (Jean-Philippe Rameau, 1737)

25) L’Incoronazione di Poppea (Claudio Monteverdi, 1642)

26) L’Enfant et les Sortilèges (Maurice Ravel, 1925)

27) Boris Godunov (Modest Mussorgsky, 1874)

28) La Traviata (Giuseppe Verdi, 1853)

29) Carmen (Georges Bizet, 1875)

30) Zar und Zimmermann (Albert Lortzing, 1837)

A little commentary may be necessary. I’ve put an asterisk next to “Götterdämmerung” because I can’t bear the thought of sitting through a complete Wagner opera again. I saw the entire Ring cycle live at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden and due to circumstances beyond my control, I was only able to get a standing room ticket for the fourth and longest of the four Ring ‘music dramas.’ I think I can probably say that standing through the entirety of “Götterdämmerung” without supertitles (this was 1982, long before the advent of that life-saving device) puts me in a class with the hardiest of opera queens~! But music of Siegfried’s Funeral March and Rhine Journey is one of the greatest moments in opera and almost unparalleled in its depth and power. Likewise the Good Friday music from “Parsifal,” but I’m unwilling to endure 5 hours of sheer boredom even for 20 minutes of the most sublime music in all opera. And while I’m fascinated with the Norns as figures in Norse mythology, there can be nothing so boring in all of opera as standing through the scene of the weaving of the Norns with no supertitles.

In contrast, I am never bored with Mozart’s ‘big four,’ which head the list. I return to Mozart again and again; he is the one opera composer with whom I could not live. Mozart was my introduction to opera: an album (back in the days of LPs) of Mozart arias sung by the Welsh soprano Margaret Price (wearing a diamond-studded black farthingale) that I borrowed from the Madison Public Library in college started it all, and I was absolutely captivated by my Joseph Losey’s “Don Giovanni” film, which I saw when it first came out in 1979.

I went through a Wagner period — which peaked when I saw the entire Ring cycle in London in 1982 — and I’ve also been swept away by operas by other composers, especially Verdi and Puccini; but no other opera composer has ever displace Mozart from my affections.

While I love “Le Nozze di Figaro,” my two absolute favorite operas are ” Così Fan Tutte” and “Die Zauberflöte,” and the only difficulty for me is choosing between the two of them. I suppose I could call it a tie, but the nature of lists is such that they are most comprehensible as a simply enumerated list, and so I’ve given the pride of place to “the Magic Flute,” the most magical of all operas.

No commentary on opera would be complete without at least a passing reference to Verdi and Puccini. Verdi is by common consent considered one of the three greatest of all opera composers, along with Mozart and Wagner, and some of Verdi’s enthusiasts would rank him first. Verdi was certainly an example of a composer — like Brahms and unlike Mozart or Mendelssohn (that most truly prodigious of all musical prodigies) — who took time to develop; despite some great individual numbers (“Va, pensiero,” the chorus of the Hebrew slaves from “Nabucco,” for example, which became the theme song of the Risorgimento), it wasn’t until the great trio of “Rigoletto,” “Il Trovatore” and “La Traviata” that he produced truly great operas. “Un Ballo in Maschera” and “Aida” are also great operas, as is “Otello,” but since this is a list of my favorite operas and not of the greatest (or at least what I consider the greatest) operas, I’m including those that I most enjoy listening to; and among those, only three make the list at all, and only one makes the top tier. Some consider “Falstaff” the least Verdian of all of Verdi’s operas, but it is the one that totally captivated me when I saw it in London in 1982 and still holds me enthralled over 30 years later.

After Mozart, though, it is Puccini who is my favorite opera composer. And while I love “La Bohème,” I’ve just heard the music too often to enjoy it the way I enjoy some of Puccini’s other operas, including the much less appreciated but arguably more musically sophisticated “La Fanciulla del West.” But it’s “Butterfly” and above all “Turandot” that swept me away when I first heard them and that still captivate me — “Butterfly” despite the obvious orientalism and exoticism; I saw “M. Butterfly” when it was on Broadway years ago and have read numerous critiques of its sexual politics, with which I largely agree; but however politically incorrect the opera may be, it still sweeps me away; it is the ‘romantic’ opera par excellence. I was fortunate enough to see a stunning production of “Butterfly” at the Teatro la Fenice when I was in Venice in 1983 before the theater burned to the ground in what was believed to have been arson. Fortunately, they rebuilt La Fenice as an exact replica of the original, earning the theater its name as a Phoenix that rises from its ashes. “Turandot” is arguably even more ‘orientalist,’ but because it is based on a fairy tale by Gozzi and makes no pretense to realism, its orientalism is arguably far less offensive.

A note on Baroque opera, which is an acquired taste even for opera lovers. I’m generally not one to sit through Handel operas because I find a long string of da capo arias to be worse than boring. The one great exception is “Giulio Cesare,” which is my favorite Handel opera and the only Baroque opera to make the top ten. Three other Baroque operas make the list, albeit further down: “Dido and Aeneas” (Henry Purcell, 1683), “Castor et Pollux” (Jean-Philippe Rameau, 1737) and “L’Incoronazione di Poppea” (Claudio Monteverdi, 1642). I’ve seen the last two staged: “Castor et Pollux” in a special production at Covent Garden (though not a production of the Royal Opera House itself) and “Poppea” at Glyndebourne in the summer of 1983. “Poppea” has its longueurs, but the ravishing duet (“Pur ti mio”) which ends the opera is surely the most exquisite music to accompany the triumph of evil in any opera in the repertoire. I’ve never seen “Dido” in the theater, even though it is in its succinct precision the most perfect Baroque opera as well as arguably the most perfect opera in my native English language (I have, however, been fortunate enough to see superb productions of both “King Arthur” and “The Fairy Queen”).

I could comment at length about every single one of the 30 operas on this list as well as a few that didn’t make it, but I’ll just share my thoughts on a few. First, a note on terminology. Clearly, the fact of spoken dialogue couldn’t disqualify either “Die Zauberflöte” or “Carmen” from being considered operas, as both are universally considered despite their spoken dialogue (the latter in the original pre-Guiraud recitative version). And similarly for “Die Fledermaus,” which is thoroughly operatic and in its own way, is a better music drama than “Götterdämmerung,” even if Johann Strauss II never aspired to the level of profundity that Richard Wagner did. “Fledermaus,” like “Falstaff” has a musical language that advances the action more expeditiously and considerably more succinctly than any of Wagner’s later operas. The same could be said of both “Madama Butterfly” and “Turandot,” my favorite Puccini operas.

Conversely, “Der Rosenkavalier,” like most Wagner operas, has considerable longueurs, but its greatest moments — including the presentation of the rose scene and the final trio and duet — are among the greatest moments in opera, and for that reason, I’ve put “Rosenkavalier” in the top tier and “Ariadne auf Naxos” in the second tier, even though I find the latter to be the most thoroughly enjoyable as well as the most consistently inspired of all of the operas of Richard Strauss.

And that is, of course, one of the difficulties in putting such a list as this together: whether to judge by the peak moments or by the opera as a whole; I’ve tended towards the latter, because there are great moments in many operas; there are individual arias and scenes of great beauty in otherwise completely mediocre operas, such as “Amor ti vieta” in Umberto Giordano’s “Fedora,” an otherwise execrable exercise in opera. In contrast, there are only passing moments of faltering inspiration in Mozart’s ‘big four,’ usually explained by the last-minute insertion of an apparently quickly written aria to please a singer (e.g., Guglielmo’s aria in “Così” and Barbara’s little ‘key’ aria in “Figaro”).

One last and very important note: this is a list of my 30 favorite operas, not of what I consider to be the 30 greatest operas ever written, though I could make a case that these represent among the 30 greatest operas; but that would require much more argumentation and analysis, and will have to await another occasion.