The Chevalier d’Éon

The Chevalier d’Éon

Who was the Chevalier d’Éon?

And why should contemporary LGBTQ people be interested in the story of d’Éon?

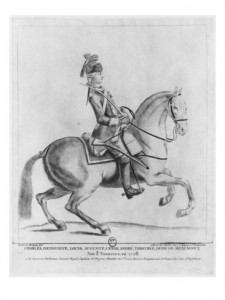

Charles-Geneviève-Louis-Auguste-André-Thimothée d’Éon de Beaumont (1728-1810) was the first openly transgendered person in European history, living the first half of his life as a man and the second half of her life as a woman. Like so many historical figures, d’Éon is a complicated figure and by no means entirely admirable; but there is no question that d’Éon is an extraordinarily important figure in transgender history despite his or her contradictions.

Charles-Geneviève-Louis-Auguste-André-Thimothée d’Éon de Beaumont was born into an aristocratic family in Tonnerre, a charming town in Burgundy that I visited back in 1992; d’Éon’s family was not exceptionally wealthy by the standards of the Ancien Régime and his position in it was on the lowest run of the French aristocracy — the French equivalent of the English landed gentry depicted so brilliantly in Jane Austen’s novels. The chevalier’s father was a lawyer and was eventually elected mayor of Tonnerre.

Chevalier d’Éon, born in Tonnerre (10.5.1728) & died in London (5.21.1810). D’Éon moved from Tonnerre to Paris in 1743 & graduated in civil law & canon law from the Collège Mazarin in 1749 at the age of 21. Louis XV recruited him into the Secret du Roi in 1756 & made him ambassador to Russia, returning to France in Oct. 1760; he became a captain of the dragoons in May 1761 & fought in the Seven Years’ War; he was named Chevalier in 1763 & appointed plenipotentiary minister; he went to England to try to create the conditions for an amphibious invasion that never happened; in oct. 1763, the Comte de Guerchy (allied with the Duc de Choiseul & Mme. de Pompadour) demoted him; Louis XV offered him a pension but he could not safely return to France. In 1774, Louis XVI succeeded Louis XV & immediately put an end to the Secret du Roi project; by this point, he was known publicly as the Chevalière d’Éon, though s/he volunteered to fight in the American Revolution, an offer that was precluded by his/her banishment; his/her pension was terminated in the wake of the French Revolution & the family estate in Tonnerre was confiscated; s/he was briefly sent to a debtor’s prison for ive months in 1804, after which she lived with the widow Mrs. Cole; s/he died bedridden in poverty at the age of 81 & was buried in the churchyard of St. Pancras Old Church & her remaining posessions were sold by Christie’s in 1813.

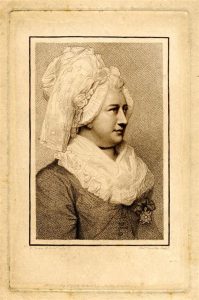

In her later years, the chevalière routinely told a story about her childhood that clearly was not true: namely, that she was born female but because her father had wanted a boy, that her parents raised her as a boy even though she was a girl; the fictionalized narrative about her sex is just one reason among many why one cannot take d’Éon’s various accounts of her life on face value but neither is it sufficient reason to condemn her given the era in which she lived.

First, as for pronouns: with d’Éon, it is not entirely clear which pronoun(s) to use; one can use masculine pronouns because d’Éon spent the first half of his life as a boy and man and was anatomically male; one could also use feminine pronouns because d’Éon clearly identified as a woman and lived the second half of her life as a woman. Using the singular ‘they’ would be anachronistic and arguably inaccurate because neither d’Éon nor his/her contemporaries would have done so in French even if there is an argument that d’Éon could be described as ‘non-binary’ in some sense. So I will alternate between masculine and feminine pronouns depending on the context.

I would also note that d’Éon’s title is gendered in French: ‘chevalier’ is related to the English word ‘cavalier’ and can best be understood in relation to the English title ‘baronet’; an English baronet would be addressed as ‘Sir’; the feminine equivalent of the masculine ‘chevalier’ is ‘chevalière,’ which is the title d’Éon used in the second half of her life.

Louis XV sent d’Éon to St. Petersburg, where he represented the French king at the court of the Empress Elizabeth, who held regular drag balls at which all members of the Russian court were required to cross dress whether they wanted to or not; it has been said that some of the big burly Russian courtiers forced to don women’s garb resented the required cross dressing but d’Éon clearly reveled in the opportunity; having established direct relations between the French king and the Russian empress, d’Éon eventually returned to France.

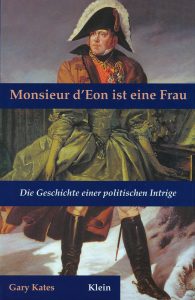

The Chevalier d’Éon’s most extraordinary escapade was as the king’s personal spy in England, where he participated in a clandestine foreign policy directed by Louis XV himself. “Monsieur d’Éon Is a Woman: A Tale of Political Intrigue and Sexual Masquerade” is a biography of the Chevalier d’Éon by Gary Kates that focuses substantially on the Chevalier’s participation in the ‘Secret du Roi,’ which the king kept secret from the foreign minister and the rest of the French government — a virtual state within the state. One of the main objectives of the ‘King’s Secret’ was to turn Poland into a French satellite; another may have been to launch an amphibian invasion of England to avenge France for the British victory in the Seven Years’ War & the British seizure of New France (the vast French territories in North America); the secret mission failed to achieve either objective and Louis XVI immediately terminated the ‘secret du roi’ upon coming to the throne.

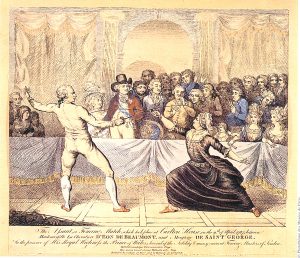

Ordered by the king himself to choose a consistent gender presentation, d’Éon decided to live the rest of his life as a woman. The Chevalière lived most of the rest of her life quietly in England; the devout and eventually elderly Roman Catholic woman later had a female roommate in London who was completely unaware of the Chevalière’s true sex, revealed upon her death by the mortician who came to embalm the body.

After d’Éon’s death, his/her fame was so great that ‘Eonism’ became a euphemism for transvestism and a British association for crossdressers was formed under the name of the Beaumont Society. When I was living in London in 1981-83, I saw a notice for a meeting of the Beaumont Society, though I never actually attended one of its meetings.

The story of the Chevalier d’Éon is a fascinating one, but why should anyone not interested in the history of 18th century France want to talk about d’Éon…? I would argue that the chevalier’s story is of signal importance for an understanding of transgender identity and LGBT/queer history even if some of the particulars of d’Éon’s story are no longer directly relevant to contemporary transgender community organizing.

The fact is, d’Éon was the first openly transgendered person in (post-Roman) European history and at the very least raised the possibility of living as more or less openly transgendered woman in European society.

“They were certainly queer in their own 18th century context,” says Kaz Rowe in a video on YouTube (“The Chevalier d’Éon: the Trans 18th Century Spy“). “Complexity does not negate the fact that the Chevalier d’Éon is a trans historical figure. We can see a modern experience mirrored in them and in their own time, they were queer, too,” adds Rowe, noting d’Éon’s bizarre and appalling ideas about Jews that unfortunately reflected the anti-Semitism pervasive in d’Éon’s day.

The Chevalière d’Éon also developed some very strange notions about gender, coming to adopt a devout Catholicism and seeing her (trans)gender identity as a kind of Christian redemption — a kind of Catholic feminism we need not spend too much time on.

I would argue that what we should take from d’Éon’s story is the possibility that even in as rigid a binary system as 18th century France, d’Éon at the very least opened up the possibility of transgender identity; even d’Éon’s alternation between gender presentations could be interpreted as anticipating non-binary identity in some fashion, especially the period of d’Éon’s active gender fluidity.

Gary Kates describes a meeting between Louis XV and the chevalier in which the king tells his most notoriously gender-ambiguous subject that he can be a man or a woman but can’t be both and orders him to choose; d’Éon chose to live as a woman, but Louis XV’s question was in fact what French society asked him/her d’Éon’s entire life.

A really important point that must be made about d’Éon is that s/he lived in an era in which hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and sex reassignment surgery (SRS) were unavailable, let along facial feminization or laser hair removal (this is not counting crude castration that has been performed for millenia); in that sense, d’Éon could be described as a ‘non-op transsexual’ (to use language from the 1980s and 1990s); in a broader sense, d’Éon is an example of someone assigned to the male sex and masculine gender who lived as a woman without any medical intervention whatsoever. Given that so many contemporary debates are about access to such medical interventions, d’Éon provides an important point of reference to the pre-modern era in which those interventions were not available and underlines an important truth: there have been people who anticipated contemporary transgender identity (I use the term ‘proto-transgenderal’) in Western and non-Western societies going back to the beginning of recorded time.

Perhaps clumsily and certainly controversially, d’Éon ultimately did manage to transcend the sex/gender binary in a way that was unprecedented in post-Roman European society and therefore deserves a special place in both European history and transgender history.

Pauline Park is a member of the Out-FM collective that produces LGBTQ-relevant programming for WBAI at 99.5 FM. She did her M.Sc. in European studies at the London School of Economics & Political Science and her Ph.D in political science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. At LSE, she studied British politics and government with Prof. Alan Sked and French politics and government with Prof. Howard Machin, writing her master’s thesis on the economic policy of the administration of François Mitterrand; she wrote her doctoral dissertation on the Maastricht Treaty on European Union.