Breaking the Silence: LGBT Identities & Multiple Oppressions

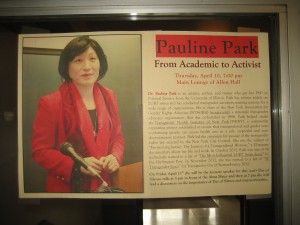

Pauline Park, Ph.D.

Chair

New York Association for Gender Rights Advocacy (NYAGRA)

and

President of the board of directors and acting executive director

Queens Pride House

Day of Silence

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC)

11 April 2014

I would like to thank Infusions for inviting me to speak at the Day of Silence event today and I would especially like to thank Danny Wenan Zheng, the president of Infusions, who was instrumental in bringing me here. It’s hard to believe that it’s now 20 years since I finished my Ph.D. here at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) way back in 1994, and I’m grateful for every opportunity to come back to C-U to visit the old alma mater, and I’m absolutely delighted to be here and to have the opportunity to talk about LGBT identities, multiple oppressions, intersectionality and community empowerment with you today. And in fact, I’ve entitled my talk “Breaking the Silence: LGBT Identities & Multiple Oppressions” because it seems to me that those are three of the crucial elements in our task.

My perspective is informed by work in the academy both in faculty and staff positions and of course as a student as well as work in the community, most intensively with Queens Pride House, which I co-founded in 1997, and the New York Association for Gender Rights Advocacy (NYAGRA), which I co-founded in 1998. Queens Pride House is the only LGBT community center in the borough of Queens, and we offer support groups — including a transgender support group, which I serve as co-coordinator — free mental health counseling for members of the community, and other services; we are just completing our first funded advocacy program which focused on advocating for members of the community — especially transgendered women of color — who are victims of police harassment and brutality.

NYAGRA is a co-founding member of the coalition seeking enactment of the Gender Expression Non-Discrimination Act (GENDA), the transgender rights bill currently pending in the New York state legislature, and I represent NYAGRA in that coalition, as I did in the coalition that secured enactment of the Dignity for All Students Act (DASA) in 2011. The Dignity Act came into effect this July and prohibits discrimination and bias-based harassment in public schools throughout the state of New York. I mention safe schools legislation in the context of this discussion because the New York State Dignity legislation includes a comprehensive list of ‘protected categories,’ including race, religion, ethnicity, and disability as well as sexual orientation and gender, defined to include gender identity and gender expression. Safe schools legislation such as DASA can help move us out of a purely ‘identitarian’ conceptual framework, which can be limiting.

For example, with both the New York State Dignity for All Students Act and the New York City Dignity in All Schools Act (NYC DASA) enacted in 2004, the diversity of the coalition itself was a major source of strength. LGBT organizations certainly constituted a core component of both coalitions, but both coalitions also included substantial participation by organizations of color; in the case of the NYC DASA Coalition, it was Asian American groups that played an especially significant role. The Asian American Legal Defense & Education Fund (AALDEF), the Coalition for Asian American Children & Families (CACF) and the Sikh Coalition, along with the New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU), were key members of the coalition, along with LGBT organizations such as NYAGRA and the Empire State Pride Agenda.

As I like to point out, when it comes to legislative work, the active participation of people and organizations of color is crucial in the success of such work; and the two DASA coalitions in which I participated demonstrate that LGBT organizations that actively engage non-LGBT-specific organizations of color can find such engagement and participation in safe schools coalitions to be fertile opportunities for collaboration and relationship-building.

It should be obvious — but may not be to everyone — that the work of breaking the silence has focused substantially on the problem of bullying and bias-based harassment in elementary and secondary schools, since so many LGBT students drop out of school because of such bullying and never make it to college; and that is as it should be, since our ability to break the silence must include our ability to make schools throughout this country safe for every student, regardless of sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, race, ethnicity, national origin, disability and every other difference that is used against students by their peers, by faculty or by non-teaching staff in our schools.

But while the origin of the Day of Silence begin with anti-bullying work, I would argue that our work in breaking the silence cannot end there; it must encompass everything that is currently diminishing the ability of both LGBT and non-LGBT people to participate fully in this society. So, for example, it must include access to health care, both in schools and on college campuses and elsewhere.

In 2009, NYAGRA published the first directory of transgender-sensitive health care providers in the New York metropolitican area; and while directories of this kind have been posted on-line for cities such as Los Angeles, Boston, and Minneapolis-St. Paul, the NYAGRA directory was the first such directory in the United States ever published in a print edition; we are updating it continuously as we identify more transgender-sensitive providers in the area and it is now available on-line as well.

In addition to the work I do on behalf of NYAGRA in the legislative arena, one other important component of my work is transgender sensitivity training; I’ve conducted sessions for a wide range of social service providers and community-based organizations, ranging from one-hour workshops to full-day trainings. A small part of my training work has been with academic institutions, focused on issues related to transgender inclusion — including, for example, gender-neutral housing, which has become a major issue on many campuses.

One of the biggest issues for transgendered people both on campus and off is access to health care, which is why I co-founded the Transgender Health Initiative of New York back in 2004. THINY (as we call it) and its members have worked tirelessly to try to open up health care to members of our community in New York, who face significant impediments to accessing quality health care, just as they do throughout the country.

In 2006, I co-facilitated a series of trainings for St. Vincent’s Hospital, which was one of the largest hospitals in New York City, and a hospital with one of the largest transgender patient populations. Sadly enough, St. Vincent’s went bankrupt last year and closed after failing to resolve a situation in which the hospital had accumulated over a billion dollars in debt. Sad, too, because these were the first transgender sensitivity trainings for any major hospital in the city and they were as much of an eye opener for us as they were for the nurses, techs, and other health care professionals we trained. Participants ranged from hostile to indifferent to open-minded to genuinely supportive in short, a microcosm of society and its attitudes towards the transgendered. Only a few of the nurses were openly hostile and even (in at least two cases) somewhat disruptive. But most of the nurses and other providers we did trainings for at the very least listened politely.

The real problem was the lack of both knowledge of the challenges facing transgendered people as they try to access health care as well as the lack of sensitivity on the part of some of these providers. In that regard, I am delighted to hear that UIUC will make its student health insurance fully transgender-inclusive starting in the fall semester 2014, covering hormone replacement therapy (HRT) 100% and providing 80% coverage for sex reassignment surgery (SRS) (which some call gender confirmation surgery); this is a significant advance and I congratulate all those who made this happen.

But one of the big problems facing our community is that among those who think about transgender access to health care —and there are far too few who think about this issue at all — most imagine that the main challenge we face is accessing hormones and surgery. In fact, the biggest challenge for transgendered people really is accessing healthcare for all of those medical issues unrelated to gender transition. And it is poor people, immigrants and people of color who are most likely to be under-insured or entirely uninsured. Which leads me to an important theme of my talk today, the need to address multiple oppressions through the lens of intersectionality in order to break the silence. Let me suggest that to do so effectively, we must avoid the erasure of multiple identities that so often accompanies the dominance of white-dominant organizations in the LGBT community.

And what precisely is the silence that we must break? First, we need to address racism and ethnocentrism in the LGBT community; second, we must also address homophobia and transgenderphobia in the LGBT community; and last but not least, we need to embrace an ethic of ethic of accountability and responsibility that enables us to empower all our communities. These are the three distinct but interrelated principles that I would like to articulate here.

Racism & Ethnocentrism in the LGBT Community

Let me begin with a story that seems to me to illustrate the compelling need to address racism and ethnocentrism in the LGBT community. In October 1998, the Audre Lorde Project (ALP) and the Gender Identity Project of what was then the Lesbian & Gay Community Services Center worked together to organize TransWorld I, the first conference specifically by and for transgendered people of color.

The Center GIP had held three previous conferences known as ‘Transgender/Transsexual Health Empowerment Conferences.’ While providing useful information about hormone replacement therapy (HRT), sex reassignment surgery (SRS), and other procedures to those pursuing a medical transition, these conferences had featured a roster of speakers who were almost all non-transgendered white men – mostly endocrinologists, surgeons, psychiatrists and others in the ‘gender industry.’

Those of us who were members of the organizing committee for TransWorld I decided that we would invite only people of color to play formal roles in speaking at the conference, in an effort to make TransWorld truly a ‘speak-out’ for transgendered people of color. I decided to call up Riki Anne Wilchins, the executive director of GenderPAC, to invite her to attend TransWorld. Riki had been, after all, instrumental in helping set up the GIP with Barbara Warren several years before as well as organizing the first Transgender/Transsexual Health Empowerment Conference. And I had taken Riki’s bona fides as an ‘anti-racist’ seriously when she had asked me to talk to participants in GenderPAC’s annual lobby day in Washington, D.C. in May 1998 on the subject of how to address issues of discrimination based on gender identity and expression when speaking with members of Congress and their staff members who were people of color.

I was all the more shocked by Riki’s response to my invitation, then, when she denounced TransWorld as a ‘racist’ conference for ‘excluding white people.’ I pointed out to Riki that everyone was invited to attend and even to speak from the floor during plenary sessions and workshops, but that we had made a point of inviting only those who identified as people of color to speak as presenters in order to make the conference truly a conversation among transgendered and gender-variant people of color.

It seemed to me that Riki’s characterization of TransWorld as a ‘racist’ event was based on a failure to understand the difference between the historic exclusion of people of color – not to mention women and LGBT people – from positions of power and privilege and the creation of ‘safe spaces’ for members of disadvantaged and oppressed communities.

There is a fundamental difference between the exclusion of people of color as well as women and LGBT people from all-white and all-male private clubs and the construction of spaces for discussion and support for such people. The difference lies in the asymmetry of power between conventionally gendered heterosexual white men and all those deemed ‘other’ in this society based on their race, ethnicity, immigration status, sexual orientation, gender or gender identity, or other characteristic. There have been organizations for LGBT/queer Asians and Pacific Islanders (APIs) for at least 20 years, but there are still people – mainly gay white men – who still label such groups as ‘racist’ if and when they insist on limiting some of their events (usually discussion groups) to queer APIs.

This is not to suggest, of course, that there are not at the very least boundary issues – for example, what constitutes ‘Asian/Pacific Islander’ for API groups or what qualifies one as a ‘person of color’ for POC organizations or who counts as a ‘woman’ in ‘women-only’ spaces. In truth, all identities and identity formations are social constructs. But those social constructions that take into account relations of power – and crucially those asymmetries of power that exist in this society as in every society – would seem to me to be the most useful.

It is when members of our community sorely uninformed on issues or race and ethnicity bring their prejudices into the public arena in campaigns for LGBT rights legislation that those prejudices can have potentially still greater consequence, as another story will illustrate. In February 2000, NYAGRA – working in partnership with the Empire State Pride Agenda, the largest lesbian and gay political organization in the state – launched the public phase of our campaign for Int. No. 24 – the transgender rights bill enacted by the New York City Council four years later. Standing on the steps of New York City Hall between two African American members of the City Council – one straight, one gay – and next to a Latina Lesbian member of the Council, I was struck by the important symbolism of having a transgendered woman of color lead the campaign for that legislation, in a city that is two-thirds people of color. Following my speech, a white transsexual activist named Melissa Sklarz spoke, loudly declaring, “When I transitioned, I lost my white skin and my white skin privilege.” Truth be told, she still looked pretty white to me. I was mortified that Melissa would make such a statement – standing on the steps of City Hall with two African American Council Members, a Latina Council Member, the executive director of the Puerto Rican Legal Defense & Education Fund, and a representative of the Asian American Legal Defense & Education Fund – and that her statement would be quoted in the news story on our press conference in Lesbian & Gay New York, the leading LGBT weekly in the city.

The working group coordinating the campaign had decided on a strategy of securing the support of people of color in the City Council and Melissa’s statement could only put into question the credibility of our commitment to forefronting the discrimination faced by transgendered people of color in the five boroughs. Fortunately, the African American who was the lead sponsor of the bill did not make an issue of Melissa’s comment.

But I am dismayed to see activists of the prominence of Riki Anne Wilchins and Melissa Sklarz make comments that clearly show a failure to understand fundamental differences between and among different forms of exclusion and oppression, and such comments and the attitudes that are made manifest by them demonstrate the need to address issues of racism and ethnocentrism within the white-dominant LGBT community.

Homophobia & Transgenderphobia in Communities of Color

At the same time, I am dismayed by the apparent lack of enthusiasm on the part of at least some LGBT people of color for addressing the homophobia and transgenderphobia that is prevalent in our communities of color. I recall one occasion when I raised the issue of homophobia and transgenderphobia in API communities at a public forum on organizing in queer API communities. At this event at the Brecht Forum in Manhattan in September 2001, my comment elicited a response from Joo-Hyun Kang, then executive director of the Audre Lorde Project, a center for LGBTST people of color based in Brooklyn. “Are you saying that people of color are more homophobic than white people?,”Joo-Hyun asked. It seemed to me a somewhat rhetorical question, to which the response was simply, “no.” I was making no comparison, but rather simply asking if we as queer APIs thought it as important to address homophobia and transgenderphobia that is prevalent in our communities of color as it is to address racism and ethnocentrism in the white-dominant LGBT community. And I would answer my own question with a definitive ‘yes.’ Indeed, to fail to do so is to abdicate our responsibility as LGBT people of color. To fail to do so would also concede our right to live openly as LGBT people in our communities of origin.

I am struck by the defensive tone of some LGBT people of color when I raise the issue of homophobia and transgenderphobia in our communities of color and the accusation implicit in their defensive response, “Are you saying that people of color are more homophobic than white people?,” that we are somehow “letting down the side” even to be admitting to the presence let alone the prevalence of homophobia and transgenderphobia in our communities of color. Such an implicit accusation is based on a binary opposition of ‘good/bad’ that suggests that we are somehow condemning our communities altogether by raising the question of anti-LGBT sentiment in those communities. But it seems to me that if we care about our communities of origin, we have both a right and an obligation to challenge homophobia and transgenderphobia in them; after all, if we don’t, who will?

I think the real question is whether or not LGBT/queer people of color are actively involved in the examination of homophobia and transgenderphobia in communities of color rather than a situation all too prevalent in which white leaders and white-led organizations engage in such a critique without being informed by any critical race consciousness. The current debates over how to respond to countries such as Uganda and Nigeria which earlier this year enacted explicitly homophobic legislation effectively criminalizing not only same-sex sexual relations but LGBT people themselves are a case in point; I would argue that we as LGBT people of color owe it to our brothers and sisters in Uganda, Nigeria, Jamaica, Malaysia and elsewhere to be actively involved in that examination; we need LGBT people of color with critical race consciousness to ensure that such discussions do not fall into the trap of a binary opposition of white LGBT ‘saviors’ and oppressed LGBT people of color as mere victims without agency or voice.

Back in November 2008, California voters passed Proposition 8, banning same-sex marriage throughout the state after thousands of same-sex couples had already received marriage licenses from San Francisco to San Diego. I participated in a massive demonstration in New York that passed by the Mormon temple on Broadway and 66th St. on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, and I remember some very good placards, including some which were very clever in taking on the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (LDS) and its role in the Prop 8 campaign. But I also remember some signs that I found problematic, including one held aloft by a gay white man declaring that “gay is the new black.” Now, those of us who are people of color know from personal experience that there are significant differences between discrimination based on race or ethnicity and that based on sexual orientation or gender identity or expression, and it is problematic to conflate or elide them.

Let me also mention an important element in racial and quasi-racial discourse that has become very nearly the dominant discourse in the United States since 9/11, and that is Islamophobia. Granted that Islam is a religion and not a race, but ‘Muslim’ and ‘Arab’ are often conflated by Americans, such as the elderly white woman who asked Sen. John McCain at a campaign event in 2008 if Barack Obama was an ‘Arab.’ I’m quite sure that woman was completely unaware of the fact that the largest Muslim-majority nation on earth is not an Arab country at all (viz., Indonesia). But given the conflation of Islam and Arabs, the rising tide of Islamophobia has had a powerful effect on communities of color in this country as well as in Europe.

After September 2001, many people of color were assaulted on the street, unfairly linked in the minds of some white Americans to the al-Qaeda attacks on the World Trade Center in Manhattan. I live in Jackson Heights in western Queens, a neighborhood with a large South Asian population; just around the corner from me is a two-block stretch of 74th St. popularly referred to as ‘Little India’ in which Sikh men with large turbans are ever-present. I vividly remember Sikh men wearing saffron-colored turbans standing on street corners and outside of subway stations handing out brochures explaining that Sikhs are neither Arab nor Muslim; of course, no one should have been harassed or assaulted because of their actual or perceived race, religion or national origin in the wake of the 9/11 attacks; but it was heart-rending to read of the attacks on Sikhs and South Asians as well as those of Arab origin and descent and anyone perceived to be Muslim in the immediate aftermath of the fall of the Two Towers. Under no circumstances should Sikhs have to explain either their religion and headdress nor their differences with others perceived (incorrectly) to be a threat to American security. I have friends — including South Asians — who have been interrogated and even harassed by Transportation Security Agency (TSA) agents at airports because of this widespread misperception of security threats. I have a friend of Libyan descent who was born and raised in the United Kingdom who was interrogated by the TSA at the airport because he has an Arab name; ironically enough, he is estranged from his family after they rejected him when his sister ‘outed’ him to the rest of the family as gay.

Another area in which Islamophobia has reared its ugly head is in discussions of Israel/Palestine, where the fact that the majority of Palestinians are at least nominally Muslim has been used in a campaign of ‘pinkwashing’ — an attempt to justify the continued illegal occupation of Palestine by the Israeli military on the pretext that Palestinian society and neighboring Arab societies are monolithically and profoundly homophobic, in contrast with a liberal Israel ostensibly better on gay rights. In fact, the actual situation is far more complex than that; but the attempts to justify the illegal occupation of the West Bank and East Jerusalem and the illegal blockade of the Gaza Strip is based on an entirely false premise, namely, that Israel is a haven for LGBT Palestinians; in fact, queer Palestinians from the West Bank and Gaza Strip are not permitted to enter Israel without special permission (which is rarely granted in practice) and Israeli law does not recognize economic or political refugees who are non-Jewish — a fact that I often find myself compelled to mention in the context of my Palestine solidarity work through New York City Queers Against Israeli Apartheid (NYC QAIA).

All of that being said, while we must recognize and address the racism and ethnocentrism — including the Islamophobia where it rears its ugly head — in much discourse on homophobia and transgenderphobia when discussing communities of color as well as countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Middle East, we must also challenge homophobes and others who deny the legitimate points of comparison between discrimination and violence based on homophobia and transgenderphobia on the one hand and that based on racism and ethnocentrism on the other, and I see significant parallels as well as quite a few significant differences. Above all, it seems to me that the failure or even outright refusal by some of our organizations to address homophobia and transgenderphobia in communities of color and in our countries and continents of origin is tantamount to an abdication of responsibility, and the consequences of that abdication of responsibility can be very real indeed for those who suffer such oppression, including the state-sanctioned oppression of LGBT people by the murderous regimes of Yoweri Museveni in Uganda and Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe, not to mention Vladimir Putin in Russia.

Racism, Institutional Power and the Noble Savage Revisited

The need for LGBT people of color to speak out in situations such as those involving the effective criminalization of LGBT people in countries such as Jamaica, Uganda, Nigeria, Egypt and Saudi Arabia, among others, speaks to another issue of signal importance, which is that of the construction of racism and a discourse of anti-racism in this country.

Let us begin by acknowledging that the problem of race and racism goes back to the founding of the republic and even before. Slavery was recognized in the Constitution of 1787 and so deeply embedded in the constitutional order of the regime that it took a civil war to resolve the question and then another hundred years of struggle to end state-sanctioned segregation. Anyone who has seen “Twelve Years a Slave” — a film based on the live of Solomon Northrup that won a well-deserved Academy Award in February — will understand how profoundly the institution of slavery has shaped the history of this country.

But we would make a mistake if we regarded the issue of race as a regional problem. It would not surprise anyone to learn that a Southern city (Charleston, South Carolina) had the largest slave population before the Civil War. But do you know which city had the second largest slave population? It was New York. After Brown vs. Board of Education prompted the formal desegregation of public school systems in the South, many in the North remained segregated due to informal systems of control, often under the guise of ‘neighborhood schools.’ Growing up on the south side of Milwaukee, my brother and I were the only non-white children in our elementary school and Milwaukee, in fact, had one of the most thoroughly segregated public school systems in the country before court-ordered desegregation in 1977.

One of the difficulties in discussing racism is the way in which it is differently construed in different communities. To many white people, ‘racism’ is an individual-level issue and the charge of ‘racism’ is often read as an accusation of personal prejudice. Most people of color, on the other hand, recognize that racism involves institutional power as well as individual bigotry. And there are some who insist that people of color cannot be ‘racist’ because they do not exercise institutional power or control institutional resources; but a simple review of the facts will demonstrate that this is not in fact the case.

As we all know, the United States elected its first African American president in 2008, and given the history of slavery and segregation in this country, Barack Obama’s election was certainly an enormous symbolic victory; but was it in fact a practical advance for people of color, including LGBT people of color? I would simply point to the fact that since his election, Obama has killed twice as many people of color in Afghanistan and Pakistan with drone strikes than George W. Bush and deported more than four times as many undocumented immigrants than Bush; how many of the victims of drone strikes or the deported immigrants were LGBT we cannot know, but some almost certainly must have been. Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have pointed out that Obama’s drone strikes are illegal under international law and may well constitute war crimes under the clear meaning of the term. And La Raza has called Obama the ‘Deporter-in-Chief.’

Obama’s defenders no doubt will point to his decision to abandon the defense of the indefensible Defense of Marriage Act signed into law by Bill Clinton and his appointment of two justices — one of them a Latina — who voted to strike down key provisions of the federal DOMA. But the key question I have posed here is whether people of color do in fact exercise institutional power in this country — the crucial point, in the view of critical race theory, as to whether people of color can be racists. And here I would point out that there are now so many African American mayors that they have formed a National Conference of Black Mayors, which counts nearly 50 mayors of cities with a population over 50,000; that’s not to mention African Americans as governor of large states, such as New York (the former governor, David Paterson) and Massachusetts (Deval Patrick) and members of the US Senate (most recently, Cory Booker, who was elected to represent New Jersey last November. We have also had two African American U.S. Secretary of States – though I doubt that most people would describe either Colin Powell or Condoleeza Rice as progressive in their policy-making when they served in the Bush administration.

Latinos and Asian Americans are also coming into political prominence, though here, too, there are to be found both progressive and exceedingly unprogressive figures. To the latter category we must surely assign Alberto Gonzalez, the attorney general of the United States in the Bush administration; the record of Obama’s African American attorney general, Eric Holder, is distinctly mixed, to say the least. I might also mention John Yoo, who served as Deputy Assistant Attorney General (in the Office of Legal Counsel) and Diet Vinh, who served as Assistant Attorney General under Gonzalez in George W. Bush’s first term. Along with Robert J. Delahunty, John Yoo (now a professor at the University of California at Berkeley School of Law) co-authored “Legal Arguments for Avoiding the Jurisdiction of the Geneva Conventions,” the notorious 42-page memo that effectively authorized the use of indefinite detention without trial as well as the use of torture by US forces in Guantanamo and elsewhere (Neil A. Lewis, “Justice Memos Explained How to Skip Prisoner Rights,” New York Times, 21 May 2004).

And Diet Vinh was the central figure in drafting the USA Patriot Act (Eric Lichtblau, “At Home in War on Terror: Viet Dinh Has Gone from Academe to a Key Behind-the-Scenes Role”, Los Angeles Times, 18 September 2002), which surely must be accounted the most Orwellian legislation ever enacted by the US Congress, a frontal assault on the Constitution and the Bill of Rights that sadly many leading Democrats such as Hillary Clinton voted for and continue to support.

It would be all too easy – and simply wrong – to dismiss figures such as Colin Powell, Condoleeza Rice, Alberto Gonzalez, John Yoo and Diet Vinh as mere ‘tokens.’ They are not tokens; in fact, they are much worse: they are people of color who exercise or have exercised real institutional power at the highest levels of government. And they have used that power largely to the detriment of people of color, both here in the United States and abroad.

As a direct result of the legal work that John Yoo did for Alberto Gonzalez, the Bush administration overturned the principle of habeas corpus, a central principle in the tradition of English common law that goes back to the signing of Magna Carta by King John in 1215. John Yoo’s work gave pseudo-legal cover for the Bush administration’s indefinite detention without charge of thousands of people in Guantanamo and in secret ‘black prisons’ in Eastern Europe. When the full record of this gross violation of human rights is finally written, it may well show that most of those detained without trial and even without legal counsel were completely innocent of the accusation of involvement with terrorism – one cannot say ‘charges’ of terrorism because most of these unfortunate individuals were never charged. Significantly, most of these individuals were and are people of color – mainly of Middle Eastern origin.

And so I would argue that the evidence shows that people of color at the highest levels of the Bush administration and the US government have participated in a concerted use of institutional power in a way that can only be described as ‘racist.’ It would seem to me that the attempt to deny our ability and capacity as people of color to commit acts of racism is to deny the reality of the complicity of at least some of us in the most unspeakable violations of human rights in decades. It hardly exonerates the likes of Rice, Gonzalez, Yoo, and Dinh that they served as the happy black, brown and yellow faces of a white administration.

I would argue that we owe it to the victims of Guantanamo to hold those responsible for such abuses accountable regardless of whether they are white or people of color. And I would also argue that we must reclaim our full humanity as people of color only by conceding the possibility of our doing evil as well as good. Only by acknowledging the bad that some people of color do in this world can we hope to have the good that some of us do as people of color fully appreciated.

And of course, Barack Obama himself is the ultimate example of the achievement of political power in this country. I know that there are a few who would argue that Obama, like any president, is a captive of the system; but if that is true, then no individual holds real power and no individual can be held accountable for his or her actions, a conclusion that I find absurd, however constricted the powers of even the president of the United States might be.

There are those in our communities of color who would exempt their fellow people of color from the capacity for racism and for evil more generally; in doing so, they pay unwitting homage to Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s celebration of the Noble Savage, incapable of evil as he is incapable of good. Writing in 1755 in A Discourse on Inequality Among Men, the French Enlightenment philosopher declared,

“Men in a state of nature do not know good and evil, but their independence, along with ‘the peacefulness of their passions, and their ignorance of vice,’ keep them from doing ill.”

It seems to me that there is behind the notion that people of color are incapable of racism the very white idea of the Noble Savage. So I see a rather enormous irony here, because those who follow Rousseau in exempting their fellow people of color from the capacity to commit this particular form of evil – namely, racism – I am certain would be among the loudest in criticizing colleges and universities for requiring the reading of the canonical texts of dead white men. And so those who limit the capacity for institutional racism only to white people unwittingly echo the words of Rousseau, among the deadest and whitest of dead white men.

I am sure that some would object that people of color do not exercise the same degree of institutional power in the United States as white people, even if they are willing to acknowledge access to institutional power by people of color at all. And I would agree. But the people of color who are being deported, who are suffering in indefinite detention in Guantanamo Bay and elsewhere, and are being targeted (accurately or inaccurately) for drone strikes most likely will not find it a comforting thought that they are denied legal redress as the result of by the actions of prominent people of color in the Obama administration as in the Bush administration.

I would urge us therefore to avoid falling into the trap of revisiting the discourse of the Noble Savage, which would deny us as people of color our capacity for good as surely as it would deny us our capacity for evil. Rather than denying the evident reality that we as people of color are beginning to come into real institutional power in this country, I would urge us to escape the limitations of an overly narrow identity politics that would have us identify with either LGBT people and/or people of color simply because they are one or the other or both; instead, we need to focus on the actions of people in power and people with power and the impact of their actions on real people, whether LGBT people and/or people of color.

I would also urge us to embrace the possibility of attaining even greater institutional power. I would urge us to embrace the possibility of using that power responsibly on behalf of our communities, in order to further empower LGBT people, people of color, and especially LGBT people of color. Rather than retreat into a discourse that would deny us our full humanity, I would urge us to embrace that full humanity. And rather than focusing exclusively or primarily on racism and ethnocentrism in the white-dominant LGBT community, I would urge us to address both racism and ethnocentrism in the LGBT community and homophobia and transgenderphobia in communities of color.

And that means approaching politics and policy from an intersectional perspective, understanding the multiple oppressions under which LGBT people of color labor as well as the opportunities for the achievement of power and therefore the need for an ethic of accountability and responsibility.

Just as those of us who are LGBT people of color cannot leave behind our racial or ethnic identities or skin color when we participate in the LGBT community, we also should not have to leave behind our LGBT identities when we participate in the life of communities of color. We owe it to our communities and we owe it to ourselves to pursue the broadest possible conception of social change and the most rigorous and inclusive as well as historically informed agenda of social justice.

And so it seems to me that we must insist on an ethic of accountability and responsibility and an analysis of politics and policy informed by critical race theory in order to understand our world and to make change in it, engaging in a process of social change that produces genuine justice and social transformation. As the Mahatma Gandhi would say, we must be the change that we seek to make in the world.

Thank you.

Pauline Park is chair of the New York Association for Gender Rights Advocacy (NYAGRA), the first statewide transgender advocacy organization in New York, which she co-founded in June 1998, and president of the board of directors and acting executive director of Queens Pride House, the LGBT community center in the borough of Queens, which she co-founded in 1997. Park led the campaign for the transgender rights law enacted by the New York City Council (Int. No. 24, enacted as Local Law 3 of 2002). She served on the working group that helped to draft guidelines — adopted by the Commission on Human Rights in December 2004 — for implementation of the new statute. Park negotiated inclusion of gender identity and expression in the Dignity for All Students Act (DASA), a safe schools bill currently pending in the New York state legislature, and the first fully transgender-inclusive legislation introduced in that body. She also serves on the steering committee of the coalition that secured enactment of the Dignity in All Schools Act by the New York City Council in September 2004. In 2005, Park became the first openly transgendered person chosen to be grand marshal of the New York City LGBT Pride March, the country’s oldest and largest pride parade. She has written widely on LGBT issues and has conducted transgender sensitivity training sessions for a wide range of social service providers and community-based organizations. Park has a Ph.D. in political science from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.