ISSUES OF TRANSGENDERED ASIAN AMERICANS AND PACIFIC ISLANDERS

By Pauline Park, co-founder, New York Association for Gender Rights Advocacy and John Manzon-Santos, Executive Director, Asian & Pacific Islander Wellness Center

Testimony submitted to the President’s Advisory Commission on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders

Transgendered and gender-variant people are among the most invisible and marginalized of all Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and it is important that our issues be addressed in any attempt to discuss the needs and concerns of the larger lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered (LGBT) Asian Pacific Islander community.

What we today would call ‘homosexuality’ and ‘transgender’ have existed throughout human history, present in some form in every pre-modern society, though they have been socially constructed in very different ways across different cultures and time periods. Most often, the two phenomena have been conflated and have been constituted through notions of a ‘third sex’ or ‘third gender’ role. In fact, in pre-modern Asian and Pacific Islander cultures, individuals whom today we would identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or intersexual, might have identified themselves as bakla (in Tagalog), shamakhami (in Bengali), waria (in Javanese), paksu mudang (in Korean), or mahu (in Hawaiian).

Mythological narratives involving sexual transformation appear throughout the oral storytelling tradition and written literature of Asian and Pacific Islander cultures, as for example, with the Chinese story of the male deity Kuan-yin, who changed sex to become the goddess of mercy. There are many popular tales of Kuan-yin’s adventures, and traditionally, she is the most popular deity in the Taoist pantheon. It is fitting that mercy should be the province of transgendered people, because the power of the transformation teaches compassion to the transformed.

Unfortunately, European colonialism had a deleterious effect on many traditions of transgender in Asia and the Pacific. For example, the Hijra of India, male temple priestesses of the mother goddess Bahuchara Mata, were turned into social pariahs during the British occupation. And the Babain culture of transgendered priests and priestesses that was revered in traditional Filipino society was destroyed by Catholic missionaries in the nineteenth century.

In Korea, there are three distinct transgenderal traditions. Under the Silla dynasty, which unified the peninsula in the 7th century, the Hwarang warrior elite included many boys who dressed as women, wearing long gowns and make-up when they were not practicing archery or preparing for battle. In addition to the Flower Boys of Silla, there were the boy actors who played women’s roles in the Namsadang theatrical troupes that toured the villages of Korea until the end of the 19th century, often taken as lovers by the older males who played the men’s roles in those same companies. Finally, there was the tradition of the mudang, always a woman, but not always female. The paksu mudang was a male shaman who performed sacred rituals as a woman (and may have lived as a woman as well), and who was not only respected but also revered. However, the mudang culture has slowly died out, under the impact of Communism in the North (where the paksu mudang were particularly popular before World War II) and capitalism and conservative Christianity in the South. Ironically enough, the mudang tradition is in fact rooted in the Altaic origins of Korean culture having its origins in the Siberian homeland from which the Korean people migrated, and it long predates the introduction of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism to the peninsula under Chinese influence after the unification of Korea under the Silla.

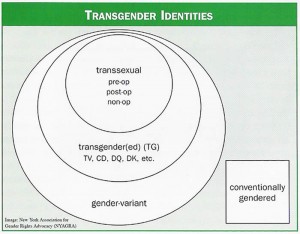

The term ‘transgender’ is of relatively recent origin, having come into general use only in the last ten years or so; it is an ‘umbrella’ term used to identify a diverse community of individuals who are similar only in transgressing conventional gender norms. The term is usually meant to include everyone from casual crossdressers and transvestites to post-operative transsexuals, as well as many individuals who are not consciously transgender-identified. There has been no comprehensive study of the transgender community, and so an estimate of the population is speculative at best. While Kinsey estimated the lesbian and gay proportion of the general population to be approximately ten percent, the percentage of Americans – and by extension, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders – who are transgendered in some sense depends to a large extent on how one defines that population.

The smallest proportion of the transgender population may well be those who are transsexual-identified – both male-to-female (MTF) and female-to-male (FTM) – ‘transsexual’ traditionally being used to describe someone seeking or having undergone sex reassignment surgery (SRS). But in addition to pre-operative and post-operative transsexuals, a growing number of individuals identify as non-operative transsexuals, those who do not seek SRS; some ‘non-op’ transsexuals may undergo hormone therapy, while others do not.

A much larger category, in which would be included transsexuals, would be those whom we could term ‘transgendered,’ whether they use that term as a self-descriptor or not. This category includes transvestites and crossdressers, the former term now considered by many to be somewhat old-fashioned or overly clinical and giving way to the latter term as a self-identifier. In that category, one could also include those who identify as or who are labeled by others as drag queens and drag kings, stone butches, etc. Non-transsexual transgendered people are those who choose to spend a significant portion of their lives in the gender opposite their sex assigned at birth without SRS.

A still larger category would be the gender-variant: individuals who transgress conventional gender norms but who do not (for the most part) ‘crossdress’; this category would include feminine men (some gay, others bisexual or heterosexual-identified) and masculine women (some lesbians, others bisexual or heterosexual-identified), as well as transgendered and transsexual people. In contrast to the gender-variant are the conventionally gendered – masculine males and feminine females who at most times and in most places conform to societal standards of gender. One important point must be made here: the lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) population and the transgender population are not mutually exclusive, nor are they coterminous. At some point in their lives, many transgendered people identify as LGB: e.g., an individual may ‘come out first as a gay male and then later come to identify as a transgendered woman; or a heterosexual-identified male may, as a post-operative transsexual woman, identify as a transsexual lesbian.

It is widely assumed that there are only two sexes – male and female – and that these form the basis of masculinity and femininity; this is what social theorists call the ‘sex/gender binary.’ Even many of those who recognize gender as being ‘socially constructed’ – i.e., in a very profound sense, ‘invented’ by human beings, just as we invent different styles of clothing – do not fully realize the extent to which sex is also socially constructed. Pioneering work by Dr. Anne Fausto-Sterling, a leading biologist, is leading to a re-evaluation of our notions of sex as well as of gender. The phenomenon of intersexuality represents one of the most significant challenges to the sex/gender binary. Intersexuals (traditionally known as ‘hermaphrodites’) are those whose genitalia are neither entirely male nor female. Because of the ‘ambiguity’ of their genitals at birth, intersexed people are subject to intersex genital mutilation (IGM), usually performed between birth and age six, in which their genitals are surgically altered to conform to socially sanctioned notions of maleness or femaleness. Many intersexuals suffer lifelong sexual dysfunction and physiological problems as a result of the brutal physical mutilation to which they are subjected, almost always in infancy or childhood, when they have neither the legal standing nor the cognitive maturity to give informed consent, much less to object, to IGM.

Intersexed people have existed in all societies and epochs, and were thought in many Asian and Pacific Islander cultures to have special spiritual powers. Therefore, a renewed respect for intersexuals would represent a rearticulation of traditional Asian and Pacific Islander cultural values as well as empowering those intersexed Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders who suffer so much shame and stigmatization. We therefore urge the Commission to make a public statement in support of an amendment to the recently passed federal law banning female genital mutilation (FGM) that would explicitly include intersex genital mutilation in its provisions. It is striking the extent to which Americans, outraged by the practice of FGM in the Middle East and Africa, are largely unaware of the equally disfiguring practice of IGM that the medical establishment condones here in the United States.

Ironically enough, while transsexuals often lack the means to obtain sex reassignment surgery, intersexuals have their sex involuntarily reassigned in a way that deprives them of autonomy in sexuality and gender expression. Sex reassignment surgery (SRS) can cost anywhere from $5,000-150,000, depending on whether the individual is MTF or FTM and the skill and reputation of the surgeon. Added to the cost of SRS itself is the cost of hormones (a lifetime expense, from the start of hormone replacement therapy), of psychotherapy, and related expenses. But the price that transsexuals pay for sex reassignment goes well beyond the costs of SRS and hormones: included in that price is lifelong stigmatization.

In order to obtain SRS, a transsexual woman or man must first undergo psychotherapy and obtain a diagnosis of ‘gender identity disorder’ (GID), a mental illness listed in the Diagnostic & Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), compiled by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). The process of transsexual transition – including psychotherapy, hormone replacement therapy (HRT), and SRS is ostensibly governed by the Standards of Care (SOC) published by the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association (HBIGDA). Together, the GID and the SOC constitute a regime for the regulation of gender, and one constructed and maintained largely by white, upper middle class, US-born, heterosexual-identified, and conventionally gendered men. One of the aims of the GID regime is to help transgendered women ¾ whom many such mental health professionals assume incorrectly to be mostly attracted to men ¾ become conventionally gendered heterosexual women, just the expectations are that transgendered men (who are incorrectly assumed to be mostly attracted to women) will become conventionally gendered heterosexual men. The fear of ‘transhomosexuality’ among such practitioners is high: they do not want to ‘create’ homosexuals (i.e., transsexual lesbians and transsexual gay men), but rather to ‘cure’ those they perceive to be homosexuals of their homosexuality.

The practical consequence of a diagnosis of ‘gender dysphoria’ or GID is that the transsexual man or woman so diagnosed is labeled mentally ill, even in those cases where he or she is perfectly mentally healthy. While there certainly are a number of transsexuals who have real mental illnesses (such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, etc.), most are no more mentally ill than non-transsexuals are. But the struggle to find or keep a job becomes a daunting one when, in order to obtain SRS, the otherwise mentally healthy transsexual has to accept a diagnosis of mental illness that could prompt discrimination based on prejudice against the mentally ill in addition to that against the transgendered. The logical solution is for the APA to remove GID entirely from the DSM. What further complicates the situation, however, is that SRS is still considered an ‘experimental’ practice (despite surgery for MTF transsexuals having been brought to a high level of sophistication), and so the diagnosis of GID is used to enable psychiatrists to ‘prescribe’ SRS as the ‘cure’ for a ‘mental illness’ that simply does not exist. It is important to realize that GID affects not only those who seek SRS: its presence in the DSM pathologizes not only transsexuals, but all transgendered people more and even more generally, all who are gender-variant. In fact, GID is diagnosed most often in gender-variant children and youth whose parents – once again, conflating homosexuality and transgender – are concerned that their children may grow up to be gay. Ironically, three quarters of the children and youth who are diagnosed with GID do in fact come to identify as LGB as adults, while only a quarter come to identify as transsexual or transgendered.

There is a growing consensus within the transgender community in favor of a ‘reform’ of GID to eliminate the designation of transsexuality as a mental illness but to retain some reference in the DSM to transsexuality as medical condition justifying HRT and SRS. We therefore call on the Commission to make a strong statement in favor of the GID reform to eliminate the designation of transsexuality as a mental illness.

The American Psychological Association has already taken a stand in favor of GID reform, stating quite clearly its belief that transgender is simply a naturally occurring variance in gender identity and expression. Just as the removal of homosexuality from the DSM 25 years ago helped significantly alter society’s view of lesbian and gay people as well as giving renewed impetus to their struggle for civil rights, so too, the removal of GID from the DSM will help remove the stigma of mental illness from transgender.

Given the profound transgenderphobia – reinforced by the GID diagnosis – it is not surprising that transgendered people constitute one of the most marginalized populations in American society, facing pervasive discrimination, harassment, abuse, and violence. The violence that is so commonplace in the lives of the transgendered was no more dramatically illustrated than in the case of Brandon Teena, a young female-bodied transman who was brutally raped and murdered in Nebraska several years ago, and whose story was told in the 1999 Academy Award-winning film, “Boys Don’t Cry.” Transgendered men and women face discrimination and violence not only in the United States, but in countries throughout the world, as documented by the International Gay & Lesbian Human Rights Commission (IGLHRC) based in San Francisco and by the Amnesty International OutFront Program based in New York. Unfortunately, many such human rights abuses take place in Asian countries.

In the face of such pervasive discrimination and violence, transgendered people, are beginning to organize its own civil rights movement, both here and abroad. Much of that political work is being done in alliance with LGB people. Hence, while there are distinct differences between homosexuality and transgender, the overlap in LGB and transgender populations and the common cause that these diverse communities have made justify the term ‘LGBT’ to describe a political community and movement.

In the last few years, the concerns of transgender communities have increasingly become integral to the lesbian, gay, and bisexual movement. Similarly, AAPI initiatives that include sexual orientation should also include the language of gender identity and expression. For example, the fear of persecution based on sexual orientation is now recognized as cause for political asylum; however, the term ‘sexual orientation’ does not necessarily include transgendered or gender-variant people. A statement from the Commission in favor of the addition of “gender identity or expression” to political asylum law would therefore help address the problem of pervasive discrimination and violence that our transgendered brothers and sisters face in many Asian and Pacific Islander countries.

It is a cruel irony indeed that transgendered people – who helped lead the Stonewall uprising that catalyzed the modern lesbian and gay movement – were marginalized in that movement after June 1969. Only in the last five years has a real transgender political movement emerged in the United States. In the 1990s, transgender political organizations formed at the local, state, and national level to press for transgender-inclusive and transgender-specific anti-discrimination and hate crimes legislation. Anti-discrimination laws that include transgender-specific language (such as gender identity and expression) have been adopted in 30 jurisdictions across the country, including one state (Minnesota), three counties, and 26 municipalities. Those cities range from the large and cosmopolitan (San Francisco, Minneapolis, Seattle, Atlanta) to the small and unexpected (Ypsilanti, Michigan; York, Pennsylvania).

A campaign is now underway in New York City to amend that city’s human rights ordinance which, if successful, would make New York City the largest jurisdiction in the country to protect transgendered people from discrimination in employment, housing, and public accommodations. The campaign is being led by a transgendered Asian woman and has elicited the support of leading Asian American organizations, such as the Asian American Legal Defense & Education Fund (AALDEF) and the Filipino Civil Rights Advocates (FilCRA). There is also a campaign to get the California state legislature to adopt similar legislation, and one of the key organizations involved in that campaign (California Alliance for Pride & Equality – CAPE) includes a number of LGB Asian Americans in its leadership. If successful, that campaign would make California – the largest state by population and one that includes a huge API community – a leader in transgender anti-discrimination law.

Little specific information exists on transgendered communities as a whole. To date there has been no community assessment of Asian American and Pacific Islander transgendered population in the U.S. From a behavioral health perspective, transgendered people are often subsumed under the larger category of gay, bisexual, and other Men who have Sex with Men (MSM). Few tracking systems allow for gender identification beyond male and female. One watershed effort was mounted in 1997 by the San Francisco Department of Public Health. The Transgender Community Health Project (TCHP) became the first study (qualitative focus groups and quantitative surveys) designed to assess HIV risk among male-to-female (MTF) and female-to-male (FTM) transgendered individuals. 505 anonymous surveys and HIV tests were administered, and risk behaviors inclusive of and beyond HIV were reported. Forty-nine, or 13%, were completed by AAPI participants.

Although TCHP data is limited in that its cohort resides in the City and County of San Francisco and its purpose was to assess HIV risk specifically, transgendered AAPIs are everywhere, often building visible communities in metropolitan areas across the U.S. More comprehensive studies on a national scope are urgently needed for transgendered people across races, including AAPIs. To the extent that findings from the TCHP study can be extrapolated as one example of an urban area where transgendered AAPIs live, work, and socialize, consider the alarming statistics below. Of the total sample of transgendered respondents (MTF% / FTM %):

52% / 41% had no health insurance

53% / 21% had unstable housing

65% / 29% had a history of incarceration

23% / 20% had been hospitalized for mental health

32% / 32% have attempted suicide

53% / 31% had been diagnosed with a sexually transmitted disease

35% / 2% tested HIV-positive

80% / 31% had a history of sex work

59% / 59% had a history of forced sex

91% / 57% use hormones

65% / 54% inject hormones

34% / 18% inject street drugs

63% / 91% report sharing syringes

According to the Comprehensive HIV Prevention Plan for San Francisco, transgendered respondents persons are at increased risk for HIV infection due to a combination of biological, economic, psychological, behavioral, social/situational and access-related cofactors. Primary among these are a much higher incidence of commercial sex work, substance abuse, poverty, lack of access to HIV/AIDS and medical services, and discrimination by AIDS service organizations as well as employers. In particular, commercial sex work, largely a result of employment discrimination and poverty is closely associated with: increased rates of injection drug use as well as substance abuse, increased STD rates, increased rates of rape and coerced unprotected sex, increased trauma to tissues during sex, history of child sexual abuse and abusive relationships, as well as dramatically increased numbers of sexual encounters and numbers of sexual partners of higher risk.

The Plan also suggests that a transgendered sex worker’s risk for HIV infection may be different from other groups. One study reports that transgendered sex workers are more likely to have receptive anal sex with their paying partners than their primary partners, a behavior with direct consequences for HIV and STD infection if protection is foregone. Preoperative transgendered sex workers who are trying to earn money for gender confirmation surgery or sexual reassignment may perceive a monetary incentive for unprotected sex as beneficial in the moment, despite the associated health risks. Feminization through hormone therapy, hair removal, plastic surgery, breast implants, and sexual reassignment surgery, although costly, is often a transgendered individual’s first priority.

Sharing unsterilized needles and syringes during injection drug use or hormone use is also common within the MTF transgendered community. Injection drug use, and in particular injected speed or crystal methamphetamine use in combination with commercial sex work is a common practice. Injection hormone therapy is seen as a positive component of the gender confirmation process, and therefore safe, though it poses many of the same HIV transmission risks as injection drug use.

Rejection and isolation are integral aspects of a transgendered sex worker’s life. Transgendered individuals are often marginalized from the mainstream gay and lesbian communities and many are ostracized by their families of origin. As a result, they have low self-esteem, neglect their own health, and are fatalistic about the future. Discrimination creates significant barriers for transgendered persons who want to maintain or seek regular employment. Eliminating discrimination during access to services is particularly important for disenfranchised groups such as transgendered individuals and sex workers. The provider of services is seen initially as a representative of a larger social system which is perceived as antagonistic to their well being. Based upon direct experience, many transgendered people distrust service providers, feel misunderstood by them, and believe that providers regard them as expendable, which further prevents access of services.

From the TCHP study, some AAPI-specific data can be gleaned. Consistent with a high HIV-seroprevalence among transgendered AAPI participants (27%), they reported high levels of HIV risk behavior, including unprotected anal intercourse and other sexual activities, as well as other co-factors such as sharing needles for the injection of hormones and street drugs. Among transgendered AAPI sex workers, the drugs of choice are injected and non-injected speed, such as crystal methamphetamine, which helps them to work late into the night. These individuals are often isolated from traditional support networks available in AAPI families and communities while language and cultural differences often limit access to health and human services. Finally, transgendered AAPIs engage in high-risk behavior but their perception of susceptibility is low, a reality consistent with gay, bisexual, and other MSM AAPIs. The transgendered AAPI population in San Francisco is estimated to number 2,500, or 40% of the local transgender population, and tend to be immigrants and refugees from Asian countries such as the Philippines, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, and China where transgendered individuals have a distinct social role.

Some nonprofit organizations report anecdotal evidence that confirm the TCHP findings. Specifically, highest among the needs of transgendered AAPIs are immigrant and refugee-competent, multi-lingual programs that broker housing, employment, and health care.

Given the complex factors which place transgendered AAPIs at high risk of disease and discrimination, targeted programs and interventions should address the following barriers:

Linguistic and cultural barriers: Asian immigrants and refugees face linguistic and cultural barriers to accessing services. Since most outreach is conducted in English, limited English individuals are not reached through mainstream channels of outreach and promotion. In addition, when health services are located, limited English proficient individuals often are unable to describe their health problems to primarily English-speaking service providers. Furthermore, providers are often unaware and even insensitive to the nuances of AAPI cultures and the needs of these individuals. For example, AAPI cultures discourage the open discussion of life-threatening illnesses for fear of inviting the disease into one’s life; thus, the superstition and fatalism attached to disease undercuts the value AAPI peoples place on prevention. The fear of stigmatization is particularly important in AAPI communities. There is fear “that any disclosure will result in community-wide disclosure of a person’s most intimate, personal life. Hence many AAPIs will not disclose outwardly nor acknowledge internally behaviors that put them at risk. Out of denial, many high-risk individuals will neither acknowledge that they are at risk nor identify with a service which targets risk behavior; consequently utilization of education prevention services is low and perpetuation of risk behavior remains high.”

Lack of health providers trained in cross-cultural delivery of services: Health care systems lack culturally responsive and linguistically appropriate services. Given the diversity of AAPIs, the health service system is simply unable to reach out to many populations, especially as AAPI populations continue to grow exponentially. In addition, effective partnerships between mainstream health organizations and community-based agencies working with limited English proficient individuals are lacking. Few AAPI language interpreters are competent in sensitive issues related to work in the sex industry, gender identity among transgendered individuals, and HIV/STD services. Many lack self-advocacy skills to effectively access health services on their own.

Socioeconomic conditions which impede access to health care system: Transgendered AAPIs who engage in sex work and exchange sex for money or drugs face immediate needs which are prioritized over seeking health services. Many sex workers are immigrants and are fearful of arrest and prostitution convictions, which could hurt their chances for naturalization. Many of the transgendered MTF AAPI sex workers, being born male, often send money home to provide for their parents in fulfillment of their filial duties.

The pervasive discrimination, harassment, abuse, and violence that transgendered people face has led to the marginalization of transgendered people, and have led transgendered AAPIs in particular into sex work and other dangerous occupations.

A strong statement from the Commission on the need to accept and appreciate the fullness of the diversity of AAPI communities would do much to help ameliorate the marginalization and the stigmatization of transgendered and gender-variant AAPIs. We would also appreciate a strong statement in favor of fully inclusive hate crimes and anti-discrimination laws at the federal, state, and local levels, as well as a statement in favor of the reform of GID. And we would view as a special priority a statement from the Commission in favor of the addition of the phrase ‘gender identity or expression’ to federal asylum law and administrative guidelines.

Transgendered, intersexual, and gender-variant people were respected and even revered in many Asian and Pacific Island cultures, from the hijra in India to the paksu mudang in Korea to the mahu in Hawai’i. Contemporary AAPIs of transgender experience have much to contribute to their AAPI communities of origin, if given the chance.

By Pauline Park & John Manzon-Santos, October 2000

Additional References / Sources

Clements, Kristen, et al; HIV Prevention & Health Service Needs of the Transgender Community in San Francisco: Results from Eleven Focus Groups; San Francisco Department of Public Health; 1997.

Clements, Kristen, et al; The Transgender Community Health Project: Descriptive Results; San Francisco Department of Public Health; 1999.

Consensus Report; San Francisco Department of Public Health; 1997.

http://www.apiwellness.org/article_tg_issues.html