Emmanuel Macron’s preference for Danish Lutherans over recalcitrant Gauls tells us more than one might think

by Pauline Park

Emmanuel Macron won the presidential election in May 2017 in good part because his opponent was the right-wing extremist Marine Le Pen, the candidate of the far right-wing Front National and daughter of the party’s founder, the notorious xenophobic bigot Jean-Marie Le Pen. The high spirits and popularity of Macron’s early months — culminating in the president’s appearance at the World Cup and celebration with the victorious French team on the field of glory in Moscow — have since given way to disappointment, disillusion, scandal and outright criminality, the ‘Affaire Benalla’ revealing Macron to be the Nixonesque figure he is: arrogant, insular, suspicious, dishonest, paranoid, conniving and utterly without scruple. It is against this backdrop that the French president’s self-inflicted shot in the foot in Copenhagen in August 2018 takes on significance beyond what otherwise might be a minor incident in the history of his cinquennat.

On August 29, Macron gave a speech to a gathering of the French community in Denmark, ostensibly about the Danish model of ‘flexisécurité.’ In the course of his speech in Copenhagen, the French president declared, “Il ne s’agit pas d’être naïf; ce qui est possible est lié à une culture, un peuple marqué par son histoire… Ce peuple luthérien, qui a vécu les transformations de ces dernières années, n’est pas exactement le Gaulois réfractaire au changement~!” (It is not a question of being naive; what is possible is linked to a culture, a people marked by its history … This Lutheran people, who have experienced the transformations of recent years, are not exactly like Gaul who are resistant to change) (“Macron, le ‘Gaulois réfractaire au changement’ et l’identité,” Agence France Presse, 29 August 2018).

Needless to say, an elected official who compares his own people unfavorably to another is unlikely to enhance his popularity by doing so, especially if done on foreign soil; and Macron’s ‘Gaulois réfractaires au changement’ line provoked a Twitter storm of images of Gauls drawn from the popular cartoon strip, “Astérix et Obélix,” two lovable Gallic goofballs from ancient times.

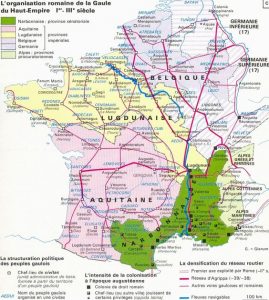

When challenged back in France, Macron reasserted his love for the French people and tried to pass off his comments about them being ‘recalcitrant Gauls’ as ironic humor. And the uproar over ‘Gaulois réfractaires’ will be seen rightly as a rather minor incident, a mere bump in the road in comparison with the profoundly damaging Affaire Benalla; but I would like to suggest that it tells us far more about Macron’s thinking and the character of his administration than may meet the eye. So at the risk of making a Gaulish mountain out of a Danish molehill, I’d like to suggest a few possibilities here. Macron’s description of the Gauls as ‘réfractaire au changement’ betrays the president’s ignorance of ancient Gaul and the remarkable adaptability of the Gauls before and after the Roman conquest; in fact, the Gauls changed considerably over time and not only in response to the invasion of Julius Caesar and the subjugation of Gaul to Roman rule. Contrary to Macron’s suggestion, pre-Roman Gaul had a complex and sophisticated society in which women had more rights and higher status than when in ancient Greek and Roman society. In the Celtic culture of pre-Roman Gaul, Druids led a complex spiritual culture that was at least the equal of Roman society’s in many respects and perhaps its superior in some. In his writings on Gaul, Julius Caesar noted that some Gauls were polyandrous, with some women have multiple husbands just as some men were polygamous and had multiple wives. Celtic Gaulish society had a spiritual culture similar to that in Celtic Britain and Ireland with a Druid culture. Julius Caesar completed the Roman conquest of Gaul between 58-49 BCE and if anyone acted like uncivilized ‘savages,’ it was the Romans, who may have killed as many as 500,000 Gauls and sold 500,000 or more into slavery. Given that violence — which some have likened to genocide — it is remarkable how relatively harmoniously Roman and Celtic cultures blended following the subjugation of Gaul as the Roman conquerors established cities along Roman lines such as Lugdunum (Lyon, founded in 43 BCE by Lucius Muatius Plancus), the capital of the Roman province of Gallia Lugdunensis.