Transgender Inclusion: Transforming the Academy, Transforming Society

Pauline Park

keynote speech

Students of the American Veterinary Medical Association (SAVMA)

Diversity Forum

21 March 14

I would like to begin by thanking Shana Kitchen of the Students of the American Veterinary Medical Association (SAVMA) for being instrumental in bringing me here to speak at the Diversity Forum today and I’d like to thank Prof. Julie Gionfriddo for first suggesting me to SAVMA as a keynote speaker. This is my very first visit to Colorado State University and in Fort Collins and only my third visit to Colorado, and I’m absolutely delighted to be here and to have the opportunity to talk about transgender inclusion in academia as well as the pursuit of social change with you today.

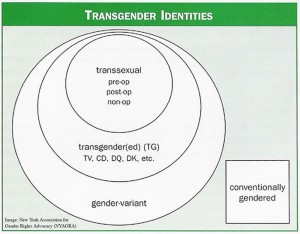

If we start with the objective of full inclusion of transgendered and gender-variant people in academic life on campus how would we go about achieving that goal? The first step would have to be to gain a full understanding of just what ‘transgender’ means. Many in this audience will have a very good understanding of transgender identity, but for those for whom this is a relatively new topic, I would like to suggest that you imagine a diagram to illustrate the complexity of the community of which I myself am a member.

Picture the community as a series of three concentric circles, beginning with transsexuals — those who seek or have obtained sex reassignment surgery (SRS) — often described as being either ‘pre-operative’ or ‘post-op,’ as the case may be. While the mainstream media until recently have tended to focus on those who follow what I call the classic transsexual transition, there are as many ways of being transgendered as there are transgendered people; most transgendered people don’t want SRS and most of those who do (viz., transsexuals) never get it — mainly because of the expense, but for other reasons as well. So encompassing this first circle composed of transsexuals is a much larger circle, those I will call ‘the transgendered,’ including not only transsexuals but non-transsexual transgendered people as well. In this group of non-transsexual transgendered people are those who identify as — or are identifed as — crossdressers as well as drag queens and drag kings — terms best used with reference to performance, whether professional or informal. The ‘transgendered’ in the context of this circles diagram will be used to denote those who present fully in a gender identity not associated with their sex assigned at birth — at least part of the time. A still larger category encompassing both transsexual and non-transsexual transgendered people is that which I will label the ‘gender-variant,’ a term that actually has its origins in academic circles but which has come into vogue among activists as well. The non-transgendered gender-variant would include relatively feminine males who nonetheless still identify as men or boys and relatively masculine females who still identify as women or girls. The term ‘gender-variant is particularly relevant on college campuses, as there are many who were born male and especially female who disdain the sex/gender binary and terms such as ‘man’ and ‘woman’ that they see as reflecting that binary; many such young people prefer to identify as ‘gender-queer’ and some prefer gender-neutral pronouns.

I contrast these three groups — the transsexual, transgendered and gender-variant — with another group, the conventionally gendered — those who more or less conform to the gender norms of their time and place, and who (by definition) constitute a majority in every society, as every society constructs norms of gender and imposes those norms on its members. What is crucial to grasp is that this diagram is a map of the gender universe; it does not speak to sexual orientation. As most in this audience will already understand, transgendered people are as diverse in their sexual orientation as non-transgendered people and like them, may be heterosexual or bisexual as well as gay or lesbian. And I also need to emphasize that this diagram is simply my map of the gender universe; there are as many different definitions of transgender as there are transgendered people.

The main point of this description of the various components of the community is to avoid the narrowing of discourse around gender identity which is constantly rearticulated and reinforced by the mainstream media — the over-reliance on what I call the classic transsexual transition narrative — which focuses almost obsessively on a linear medical transition from male to female through hormone replacement therapy (HRT) towards the end point of sex reassignment surgery; while some do follow that path, most transgendered people do not. Any effort to establish fully-transgender inclusive programs and services on a college campus will falter unless it is based on a recognition of the full diversity of transgender identity, and the truth that there are as many ways to be transgendered as there are transgendered people.

Transgendering the Academy: Campus Policies, Curriculum, Student Services, and Faculty and Staff Development

Having attempted to describe the diversity of the transgender community, I would now like to set out what I see as four crucial elements in what I call ‘transgendering the academy.’ These include: first, establishing campus policies and protocols that explicitly prohibit discrimination based on gender identity and expression; second, advancing transgender entry into faculty positions within academia; third, constructing curricula and building academic programs and departments that advance the study of transgender in the academy; fourth, establishing an institutional infrastructure of services for transgendered students, faculty and staff; and fifth, constructing theory that is relevant to activism, advocacy and public policy.

One of the tasks that must be undertaken in order to effect what I am calling the ‘transgendering’ of the academy is the adoption by colleges and universities of policies explicitly prohibiting discrimination based on gender identity and gender expression as well as sexual orientation, and I was delighted to discover that Colorado State has adopted such a policy and that that policy is explicitly included in CSU’s student code of conduct. There is a curious paradox here: where campuses are situated in jurisdictions that currently include gender identity and expression in non-discrimination law, explicit policies that do so are somewhat redundant, as such colleges and universities are then under legal mandate to enforce non-discrimination. But I would argue that campus policies are still useful even in cities, counties and states with gender identity and expression in human rights law, as they represent an explicit commitment on the part of the college or university to transgender inclusion, and they send a signal to transgendered students, faculty and staff that their presence and participation in campus life are valued, as well as sending an important signal to those who would discriminate against transgendered members of the campus community.

Of all the items in the project of transgendering the academy, this is, on the face of it, the easiest: simply adding either gender identity and expression to the college or university non-discrimination policy or — better still — adding a definition of gender that includes identity and expression — requires no elaborate word-smithing or lawyering, merely a commitment on the part of the administration to do so. The difficulty comes when applying such a non-discrimination policy to specific situations such as sex-segregated facilities, including those where there is the possibility of unavoidable nudity (to use a legal expression). Restrooms, dormitories, and gyms and locker rooms are the most significant ’sites of contestation’ (to use a term beloved of post-structuralist theorists). Some institutions, such as New York University (NYU), have adopted policies that specifically require the construction of at least one gender-neutral restroom per new building.

Explicit campus-wide policies ensuring full access to campus facilities for transgendered students as well as faculty and staff are important but must be drafted in ways that address the potentially thorny issues that arise when it comes to sex-segregated facilities. The rule should be one of reasonable accommodation, backed by an aggressive effort by the administration to ensure full access to such facilities. The prohibition of discrimination based on gender identity and expression must be explicitly included in faculty, staff and student handbooks along with prohibition of discrimination based on other characteristics such as race, ethnicity, religion, national origin, disability, etc. Above all, the prohibition of discrimination based on gender identity or expression must be included in legal documents that ensure the right of the student or faculty or staff member to litigate a dispute if necessary; only then can the institution be held accountable, especially in jurisdictions which do not include gender identity or expression in state or local non-discrimination law.

Single-sex colleges must also address the issue of admissions policies, a particularly thorny issue for women’s colleges; but the inclusion of both transmen and transwomen in women’s spaces is an issue that will not go away, much as many administrators at women’s colleges may wish it to. Clearly, the principle of empowering women through education needs to be subjected to scrutiny, as does the very definition of what constitutes a woman, and what provisions must be made to accommodate and ideally to fully include in the life of the college those female-born individuals who transition to male over the course of their undergraduate careers at women’s colleges, as well as those male-born individuals who seek admission to a women’s college as women. In April 2013, I spoke to faculty, staff and students at Mills College in Oakland about the challenges of making a women’s college fully transgender-inclusive (“Transgendering the Academy: Transgender Inclusion at a Women’s College“).

Colleges and universities should also mandate transgender sensitivity training for all faculty and staff — and where feasible — for students as well. Where mandatory diversity training already exists for race, ethnicity, religion and disability as well as sex or gender, that training should include sexual orientation and gender identity and expression as well. In other words, ‘diversity’ needs to be redefined campus-wide to include diversity of sexual orientation and gender identity and expression.

Another mechanism for enhancing inclusion would be inclusion in a campus-wide census of students, faculty and staff — especially those in leadership positions — that includes self-identification by sexual orientation and gender identity. No doubt such a proposal could meet resistance even at more ostensibly more progressive colleges and universities. But at the very least, surveys of ‘campus climate’ should include questions about climate for LGBTQ students, faculty and staff.

The second element in the project of transgendering the academy is the inclusion of transgender-relevant courses in the curriculum of institutions of higher education. Inclusion of a course on transgender issues as a requirement for completion of a major or minor in LGBT studies would also represent a significant advance for transgender inclusion in the curriculum. On the curricular front, at least, there has been some progress over the course of the last few decades, as the number of courses offered at colleges and universities in the United States and Canada — and increasingly outside North America — that include a substantial component on transgender issues has grown exponentially, albeit from a small base. Once again, there seems to be no comprehensive list, which would be very useful for LGBT campus professionals as well as for students and faculty. And all too often, even where transgender-inclusive courses are included in a college course catalog, those courses are offered irregularly and by graduate students or adjunct professors who have little institutional influence and limited ability to ensure continuity in course content from semester to semester. But where such courses exist, they are primarily in the humanities and to a lesser extent in the social sciences. In other fields, significant transgender- or even LGBT-specific content in curricula is rare. In schools of medicine, transgender-specific content is sparse, and what little there is focuses almost exclusively on the medical aspects of transsexual transition, even though familiarizing physicians and other health care providers with what might be termed the ‘psychosocial’ aspects of health care provision may be as important in ensuring transgender access to quality health care as ‘cognate’ knowledge of the surgical and endocrinological aspects of gender transition. I would suggest that a minimum of two hours of transgender sensitivity training should be required at every school of medicine that offers an M.D.

Inextricably linked with the issue of curriculum development is that of faculty and staff development. Certainly, one of the biggest challenges in advancing a project of transgendering the academy will be that of transgendering the faculty of colleges and universities, few of whom have many openly transgendered members; even fewer transgender-identified faculty members obtain tenure after having been hired while openly transgendered; and still fewer obtain tenure primarily for research focused on transgender issues. And most theorists who focus substantially on transgender issues are in the humanities, with a scattering in the social sciences.

Indeed, one of the most remarkable facts about what might be termed ‘transgender studies’ is that many if not most tenured faculty members who are in the field are not themselves transgender-identified; and those who are for the most part are graduate students and adjunct faculty. What if the faculty of a program or department of women’s studies at a college or university was almost entirely male? Or consider for a moment a comparison with ethnic studies: imagine for a moment if a program or department of African American, Asian American, Native American or Latino studies on a given college campus were mostly or even entirely white; such a situation would be regarded as controversial if not unacceptable by many students, faculty and administrators alike. And yet, transgender studies — depending on how one defines the field — may be very close to that situation today. There are, of course, significant differences between race and ethnicity on the one hand and sexual orientation and gender identity or expression on the other, and it would be risky indeed to make to glib a comparison between them. And yet, entertaining the analogy for the moment may be useful in pointing out the striking asymmetry in power relations between the majority of those who participate in this nascent field called transgender studies who are students, untenured faculty and independent scholars as well as activists and the minority who as tenured faculty members who constitute the privileged elite of this small society of largely white and upper middle class academicians.

Even more problematic is the tendency of transgender studies as a field to mirror the larger academic society’s tendency to construct and rigidly enforce orthodoxies of thought as well as hierarchies of power, both within and outside the academy. The clinical literature is dominated by psychiatrists, psychoanalysts and psychotherapists, with some participation by social workers and other members of the ‘helping professions,’ but the transgendered people whose lives are profoundly affected by the determinations of those professionals are excluded from participation in the construction of that literature for lack of the professional credentials required for that participation.

If transgendered people have made little headway in attempting to secure tenure in traditional academic departments, they have made even less progress in schools of medicine where psychiatrists earn their MDs. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is among professional associations in the ‘helping professions’ possibly the least open to participation by the transgendered and the least open to public or LGBT community input of any kind, despite the vast influence over the lives of transsexual, transgendered and gender-variant children, youth and adults wielded by the psychiatric profession.

Not unrelated to transgender faculty development is the issue of transgender-inclusive curricular development. Certainly, non-transgendered faculty members can and do participate in the development of transgender-inclusive curriculum; but for the reasons already stated, the asymmetry in institutional power between transgender-identified students and faculty who develop and teach so many transgender-inclusive courses and the tenured faculty who wield decision-making power over them as well as curriculum development poses a serious issue for academic institutions.

Another important issue is the institutional standing of transgender studies and LGBT studies more broadly speaking. First, there is the question of programs vs. departments. In most colleges and universities, departments have far greater autonomy than programs and are far better placed to defend faculty lines and budgets against cutbacks than programs; that is no doubt why the faculty members participating in the development of women’s studies in the United States have aimed towards the establishment of departments of women’s studies wherever possible.

I noted while looking at the university’s website that you have a Center for Women’s Studies & Gender Research here, currently staffed by a director and two instructors (one temporary), and that it is housed within the ethnic studies department. I also noticed two LGBT studies courses in the CSU course catalog: Queer Studies and Women of Color (ETST 300) and Queer Creative Expressions (ETST 413). I would be interested to hear about the course content, how often the courses are taught, by what level of faculty, and whether there are courses in any other department that are LGBT-specific or LGBT-focused, and if so, how much content is transgender-specific. I would also be interested to hear whether the Center for Women’s Studies & Gender Research has the ability to offer tenure-track positions of its own entirely independent of other academic units, or whether the ethnic studies department has any interest in hiring tenured or tenure-track faculty who focus on LGBT studies and specifically on transgender studies.

Of course, there is the question as to whether this field that I am calling ‘transgender studies’ is better thought of as a subset of LGBT studies or of ‘gender studies’ and therefore better housed in a program or department of sexuality studies or one of women’s or gender studies. There are, of course, universities that have combined the two, such as the Center for Gender Studies at the University of Chicago, for example, which houses the Lesbian & Gay Studies Project and, according to its mission statement, “consolidates work on gender and sexuality, and in feminist, gay and lesbian, and queer studies.”

Then there is the question of institutional infrastructure, especially of student services. Here, the Consortium of Higher Education Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Resource Professionals (’the Consortium’) and its members have played a leading role in developing LGBT student services offices at campuses around the United States. There is much to say about services specifically needed by transgendered and gender-variant students, but given that the primary focus of my talk is on public policy and advocacy, I will touch on only a few programmatic elements that I think are important to the development of infrastructure serving undergraduate and graduate students on campus.

Obviously, a fully funded LGBT student services office with at least one or more full-time staff members is the minimum needed to effectively serve transgendered and gender-variant students, and in that regard, it’s good to see that there is a GLBTQQA Resource Center here at Colorado State, which I understand was founded in 1997 and opened in 1998. I would certainly hope that the university administration is committed to adequate funding for the Center and to increasing funding if it is not. I was also interested to see that an LGBT alumni association has been formed here and I would be interested to know how much degree of autonomy from the general alumni association it enjoys.

One of the challenges facing offices of LGBT student services is the ’silo-ing’ that often results from the construction of offices of multicultural affairs along identitarian lines, such that the office of LGBT students primarily serves white queers, with little engagement with the offices of African American, Latino, or Asian American students, which in turn are inadvertently relieved of the obligation to serve LGBT students of color within their constituencies. Housing the LGBT student services office within the same complex as those serving students of color — such as is apparently done here — can help foster collaboration and collaborative programming. Colleges and universities must work to ensure that LGBT students of color and especially transgendered students of color do not fall between the cracks. ‘Intersectionality’ must not be simply a slogan; it must be a principle upon which the work of student service professionals at colleges and universities operate.

Also important for colleges and universities are support groups for those coming out and/or transitioning. Transgendered students also need support and guidance in navigating the physical infrastructure of a campus, including access to restrooms and locker rooms in gyms. Housing is also an important issue, and single-sex institutions — especially women’s colleges are increasingly confronted with issues of access. Health care is a particularly important and sensitive issue for transgendered students, the same issues that prompted a number of us to start the Transgender Health Initiative of New York (THINY) in 2004, a project designed to enhance access to health care for transgendered and gender-variant people in the metropolitan area. Transgendered students face multiple and significant impediments when they attempt to access procedures and care both related to gender transition and not directly gender-related, both on and off campus. Offices of LGBT student services can also play a role in assisting transgendered and gender-variant students navigate what might be called the ’semiotics of campus life,’ including negotiating classroom etiquette related to names and pronouns and even posting transgender-affirming signage around campus.

Let me conclude with the component of this effort that is the most fraught with difficulty. If this project of transgendering the academy is to succeed, the field of what may be termed ‘transgender studies’ must demonstrate its relevance to the community which is the ostensible object of its study. Within the academy, the central justification for that enterprise which we may term ‘theory construction’ is that it creates new knowledge, illuminating the human condition, or — in social science terms — describing, explaining, and predicting the phenomena which are the objects of its study. What might be called ‘transgender studies’ is in fact a kind of intersection of two overlapping fields — LGBT studies and gender studies (still known as women’s studies in many colleges and universities).

There are in fact three distinct literatures concerning transgender identity, none of which communicate with each other. There is, first of all, what might be called the clinical literature of psychiatry, psychotherapy and social work. Second, there is the literature of gender studies influenced by feminist theory and especially the stream of queer theory that has its origins in the work of post-structuralist theoreticians, above all, that of Michel Foucault (The History of Sexuality being the origin of this literature). And finally, there is a small theoretical literature in the social sciences of a more positivist and empirical nature.

The problem with the clinical literature — especially that developed by psychiatrists — is that it articulates a pathologizing discourse in which all forms of gender variance are viewed as deviant aberration from a heteronormative standard. At the heart of this literature is the diagnosis of gender identity disorder (GID), listed in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic & Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and revised in the DSM-V as ‘gender dysphoria’ — largely a semantic definition, given that the diagnosis still pathologizes transgender identity as a mental illness. Even those psychiatrists, psychotherapists and social workers who are sympathetic to transsexual and transgendered people seeking some sort of gender transition are compelled by the logic of the medicalization of transgender identity to view transsexualism as a condition to be treated through interventions such as psychotherapy, psychiatry, HRT and SRS. No matter how helpful in practical terms to those seeking to transition in facilitating access to desired medical interventions, the discourse of GID is one which subjects the transgendered individual to treatment for a medicalized condition rather than viewing transgender identity as simply a naturally occurring variant in gender identity and expression.

In a speech I gave at the Trans-Health Conference in Philadelphia in April 2007, I called for the removal of GID from the DSM, contingent on the establishment of mechanisms to ensure continued access to and payment for procedures and surgeries related to gender transition. As I like to say, I do not have a gender identity disorder; it is society that has a gender identity disorder. Last year, the APA issued the fifth edition of the DSM, which substitutes ‘gender dysphoria for the diagnosis of GID; but the softening of the harsh language of the GID diagnosis still leaves in place a diagnosis that continues to pathologize transgender identity and other forms of gender variance as a mental disorder that needs to be corrected, and that diagnosis not only undergirds the Standards of Care (SOC) published by the World Professional Association of Transgender Health (WPATH) (formerly the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association) and the protocols for gender transition in this society, this diagnosis – what I call the GID ‘regime’ – constitutes the very basis for American society’s understanding of transgender. Even in relatively more sympathetic portrayals of transgendered characters such as those in “TransAmerica” and on “All My Children” and “Ugly Betty,” the discourse through which those characters are understood is a medical model of transsexuality that is fundamentally model that constructs gender dysphoria as deviance from a norm rather than recognizing transgender and gender-transgressive identity and expression as simply being a natural variance in a gender identity that is no more ‘disordered’ than conventional gender identity and expression.

I would argue, we need to view transgender not exclusively or even primarily through the prism of a narrow medicalized discourse but rather through the lens of progressive politics and the pursuit of social justice and social change. And that means reconceptualizing identity in non-pathologizing terms and connecting transgender identity with a transgender community, an LGBT community and other communities, as well as constructing community as the basis for a movement. That in turn means connecting our struggle as transgendered people with the struggles of poor people and people of color as well as immigrants — not difficult to do, since so many of us, especially in this country, are poor people and people of color as well as immigrants. We need to talk about multiple oppressions based on race, ethnicity, citizenship status, religion, national origin, class and dis/ability, among so many other things, and the intersectionality of these oppressions. And we need to talk about the role of students and academic theorists in helping bring about such change.

The influence of GID also extends into the sphere of public policy as well, impeding the fight for transgender rights. We have made enormous progress as a community and as a movement over the course of the last two decades, but while over 150 jurisdictions — including 17 states and the District of Columbia – now have enacted legislation explicitly prohibiting discrimination based on gender identity or expression, it is a sad fact that 33 states have no such protection in their state laws. However, every state has included disability in its human rights law, and it is that rubric that litigators are using to obtain legal redress for transgendered plaintiffs across the country, and they often win on that basis. But the argument that such litigators proffer usually follows along these lines: my client is mentally ill by virtue of his/her gender identity disorder or gender dysphoria and therefore is protected under state disability law. I should make clear that I have nothing but admiration for the hard-working lawyers who represent transgendered clients – often pro bono – with limited time and resources. And in those 33 states without explicit inclusion of gender identity and expression in state human rights law, appeal to disability by way of GID may well be the only practical way of obtaining legal redress for discrimination against a transgendered client. But I think we need to recognize how sharp the horns of that dilemma may be.

As a non-lawyer who works on legislation, I can tell you that the genuine happiness that I feel for the transgendered client who wins such a case is diminished by the realization that the victory for that individual undercuts the very arguments that we need to make in the legislative arena. Because it is precisely GID that gives the religious right and other opponents of transgender rights legislation their most powerful ammunition. So I would argue that we need to move from a ‘deviance’ model to a ‘variance’ model and from a construction of transgender identity as a mental pathology to a concept of ‘wellness’ in which transgendered and gender-variant people are viewed not as vectors of mental illness and disease but rather are recognized as contributors to society, including potential contributors to a transformation of society’s understanding of gender.

The clinical literature is profoundly compromised by the profound transgenderphobia of the clinicians who dominate that literature and who are largely white, upper middle class, conventionally gendered, heterosexual men. But the queer-theoretic literature that is its leading competition in the field of transgender studies, while ostensibly more sympathetic to the transgendered and gender-variant people who are the subjects of its study, is also characterized by limited community participation and problematic discourse.

While the literature of transgender studies influenced by feminist and queer theory is more sympathetic to transgender community members and generally far less pathologizing than the clinical literature of psychiatry, it is one of the most obvious defects of much of the queer-theoretic literature on gender identity and expression that so much of it is inaccessible to so many members of the community that are the subject of the theorist’s gaze. Not all, certainly, but much of the literature of transgender studies is written in a style so abstruse if not deliberately obscurantist that it is inaccessible to anyone outside the field, including activists, advocacy organizations and policy-makers. None of this is to suggest, of course, that all theoretical literature must be written at a sixth-grade level or in a language that completely excludes all specialized terminology; such a demand would render difficult if not impossible the kind of nuanced and sophisticated discussions of important problems in theory construction that are an appropriate part of academic discourse. And one must resist the anti-intellectualism endemic in American society that is also all too apparent in certain LGBT activist circles.

But any honest academic would have to admit that a goodly portion of scholarly activity is really devoted primarily to the attainment of tenure and promotion; were that set of institutional incentives removed, one suspects that quite a few university presses and even whole journals might go out of publication in short order.

Much of what may be termed as ‘transgender studies’ — including that written in a queer-theoretic vein — is written from a white, upper-middle-class, US-centric perspective. Transgender studies as a field needs to take into account not only perspectives of transgendered people of color, but the full complexity of intersectionality, examining class, disability, and citizenship and nationality issues as well as race and ethnicity; and transgender studies must also incorporate the wide world outside the United States in its perspectives and concerns. At the same time, if it is to be valuable, transgender studies must do more than simply preach to the choir. Research and writing that does nothing than enable the author to strike a pose does nothing to advance our understanding of the complexities of gender identity and expression, much less the marginalized communities that are the ostensible object of the author’s screed. Participants in the enterprise of transgender studies must avoid sanctimonious moralizing and instead attempt to engage meaningfully with those inside the academy and out in order to attempt to enlist them as allies.

What post-structuralist theory at its best can do is help deconstruct problematic discursive practices prevalent in public policy discussions as well as in much of LGBT activism and advocacy work. One of the most problematic such tendencies in transgender activism and LGBT activism more generally is the conjuncture of biological essentialism with liberal rights discourse, as in the formulation, “I was born gay/lesbian/bisexual/ transgendered; my sexual orientation and/or gender identity is an immutable characteristic; therefore, I deserve legal rights.” Such a formulation cries out for deconstruction, but attempts to bring academicians informed by post-structuralist theory together with activists advocating on behalf of marginalized communities within a political system characterized by a strongly concretized constituency politics do not always bear fruit.

What I would like to suggest, therefore, is that activists and academic theorists do have something to learn from each other. Transgender and LGBT activists would benefit by subjecting their discursive practices to interrogation and deconstruction of a reflective and productive sort. For example, activists and advocacy organizations pursuing an equality agenda both in the United States and abroad need to engage the public in a way that does not rely on problematic and even counter-productive notions such as are found at the intersection of biological essentialism and liberal rights discourse.

Conversely, academics would profit by examining the relevance of their theory construction by talking with activists and policy-makers to — in a post-positivist but nonetheless meaningfully ‘empirical’ sense — ‘testing’ their ideas in the ‘real’ world and striving for policy relevance where appropriate. Some direct involvement with activism and advocacy work ‘on the ground’ might also help inform theory construction. Not all theory construction need be ‘relevant’ in a direct way, and not all activism need be conceptually sophisticated. But the gulf between theory and praxis in transgender studies resembles a yawning chasm, a veritable Grand Canyon without the scenic beauty.

And that brings me to the third literature of transgender studies, which is the conventional social scientific sort found in scattered bits and pieces in social science journals as well as in publications of LGBT organizations. This is a relatively small literature compared with the clinical literature and the queer theory literature, but some of this empirical literature is genuinely policy relevant, even if it is not always as theoretically groundbreaking as the best of the queer theoretic writing. What we need are more studies examining the serious problem of homelessness among queer youth in the United States and other specific populations — the transgender community, people of color, elders, and LGBT families — as well as policy areas such as mental health care, substance abuse, housing, social support, and violence. It seems to me that the question is one of how transgender-supportive students, faculty and staff can work to ensure that the deliberations of public policy makers are informed by research and scholarship that is in turn informed by the lived experiences of transgendered and gender-variant people.

I would like to see us engage the project of transgendering the academy in earnest, and success of that project can only be premised on a transformation of the relationship between theory and praxis. Only when the academy begins to foster public policy and activism in the United States and abroad that is a informed by feminist consciousness and that takes into account the insights of post-structuralist theory without being overly encumbered by institutional imperatives of publication for tenure and promotion can it make a significant contribution to the pursuit of a progressive vision of social justice and social change.

Activism & the Academy: Turning Theory Into Praxis

So how do we take genuine insights generated within the academy and go on to make real social change outside the groves of academe…? In order to do that, we first need to rethink how we think about transgender, which means rethinking gender more generally. My own work as a transgender activist is informed by a feminist conception of gender and a commitment to challenging and dismantling the sex/gender binary that is at the root of our oppression as women and as men as well as transgendered men and women. Our goal as a movement must therefore be nothing less than the transformation of society’s understanding of gender. And if we are committed to that goal, we must also be committed to dismantling the ‘GID regime’ that undergirds this system of gender regulation and control.

Allow me to make a few practical suggestions. I would like to mention these possible fields for productive work: discrimination, bias-based harassment — particularly in schools, policing and criminal justice reform, and access to health care. I have worked in all of these areas through organizations in New York, most intensively with Queens Pride House, which I co-founded in 1997, and the New York Association for Gender Rights Advocacy (NYAGRA), which I co-founded in 1998.

First, with regard to discrimination, NYAGRA led the campaign for the transgender rights law enacted by the New York City Council in 2002. And NYAGRA is a co-founding member of the coalition seeking enactment of the Gender Expression Non-Discrimination Act (GENDA), the transgender rights bill pending in the New York state legislature since 2002. While over 150 localities and 17 states as well as the District of Columbia now explicitly prohibit discrimination based on gender identity and expression, 33 states and a majority of cities and counties do not, and we have to work to ensure enactment of such statutes at the federal as well as the state and local levels throughout this country. We also have to support LGBT activists in other countries, including in Russia, Uganda, Nigeria and Jamaica, where one risks one’s life to come out as LGBT.

It should be obvious — but may not be to everyone — that making higher education more LGBT-inclusive must also mean tackling the problem of bullying and bias-based harassment in elementary and secondary schools, since so many LGBT students drop out of school because of such bullying and never make it to college; that is especially true of transgendered students, I would essay, based on anecdotal evidence (in the absence of any comprehensive study of the problem).

I represented NYAGRA in the coalition that secured enactment of the Dignity for All Students Act (DASA) in 2011. The Dignity Act came into effect last July and prohibits discrimination and bias-based harassment in public schools throughout the state of New York. I mention safe schools legislation in the context of this discussion because the New York State Dignity legislation includes a comprehensive list of ‘protected categories,’ including race, religion, ethnicity, and disability as well as sexual orientation and gender, defined to include gender identity and gender expression. Safe schools legislation such as DASA can help move us out of a purely ‘identitarian’ conceptual framework, which can be limiting.

And mental health support is and has to be a key component of health care. At Queens Pride House, we offer support groups — including a transgender support group — free mental health counseling for members of the community, and other services.

This is an ambitious agenda, but it is one in which every single one of us can participate. You do not need to have a badge with the word ‘activist’ to get involved in the work; I certainly didn’t have any such badge or credentials when I started getting involved in activism. And you do not need to be paid for the work, of course; in fact, there are relatively few paid positions in LGBT organizations or LGBT programs of non-LGBT organizations, and still fewer that are transgender-specific. But the need is infinite, so if you’re willing to work on an unpaid volunteer basis, there will be possibility of running out of work to do if you’re interested in it.

Much of this work can be done on campus. It can be as easy as mentioning the need for transgender-inclusive language and content in an academic course or project. It’s also important to stress that some of the most important work that can be done may come in one-on-one interactions with friends, family members, fellow students and colleagues. It can be as simple as having a conversation about transgender issues, or speaking up when something ignorant or offensive is said in class or in an informal conversation or group discussion. The most important thing is simply to begin to regard yourself as an agent of social justice and social change. As the Mahatma Gandhi would say, we must be the change that we seek to make in the world. Thank you.

* * * * *

Pauline Park (paulinepark.com) is chair of the New York Association for Gender Rights Advocacy (NYAGRA) (nyagra.com), a statewide transgender advocacy organization that she co-founded in 1998, and president of the board of directors and acting executive director of Queens Pride House (queenspridehouse.org), which she co-founded in 1997.

Park named and helped create the Transgender Health Initiative of New York (THINY), a community organizing project established by TLDEF and NYAGRA to ensure that transgendered and gender non-conforming people can access health care in a safe, respectful and non-discriminatory manner. And as executive editor, she oversaw the creation and publication in July 2009 of the NYAGRA transgender health care provider directory, the first directory of transgender-sensitive health care providers in the New York City metropolitan area and the first directory of transgender-sensitive health care providers published in print format anywhere in the United States.

Park led the campaign for passage of the transgender rights law enacted by the New York City Council in 2002. She served on the working group that helped to draft guidelines — adopted by the Commission on Human Rights in December 2004 — for implementation of the new statute. Park negotiated inclusion of gender identity and expression in the Dignity for All Students Act (DASA), a safe schools law enacted by the New York state legislature in 2010, and the first fully transgender-inclusive legislation enacted by that body, and she is a member of the statewide task force created to implement the statute. She also served on the steering committee of the coalition that secured enactment of the Dignity in All Schools Act by the New York City Council in September 2004.

Park did her B.A. in philosophy at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, her M.Sc. in European Studies at the London School of Economics and her Ph.D. in political science at the University of Illinois at Urbana. Park has written widely on LGBT issues and has conducted transgender sensitivity training sessions for a wide range of organizations. In 2005, Park became the first openly transgendered grand marshal of the New York City Pride March. She was the subject of “Envisioning Justice: The Journey of a Transgendered Woman,” a 32-minute documentary about her life and work by documentarian Larry Tung that premiered at the New York LGBT Film Festival (NewFest) in 2008. In April 2013, Park was named to the inaugural Trans 100 list of leading activists and community members.