Israel & the Ottoman expulsion of Jews from Palestine in 1917

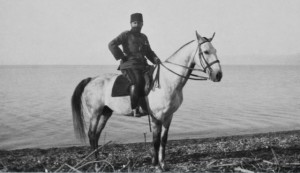

Ahmed Jemal Pasha on the banks of the Dead Sea

“April 6, 1917 was the day set by the Ottoman authorities then ruling Palestine for the evacuation of the civilian population of Tel Aviv and Jaffa. Although the Muslims who were expelled were permitted to return to their homes within days, the Jews were not able to come back to the city until after the British conquest of Palestine, later that same year,” writes David B. Green in Ha’aretz. Reading today’s “This Day in Jewish History” brings a strange sense of déjà vu, as the Israeli government is now doing to the indigenous Palestinians what the Ottoman Turkish authorities apparently did on this day in 1917 — forcibly deport them from their homes & their land (in this case, to Egypt). I’ve heard many Zionists justify the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians based either on the Holocaust (for which it would be rather fantastical to lay blame on the Palestinian people) and/or on the fact that Jewish militias won the war of 1947-48 as well as the 1967 war. If the conquest of a territory gives one the right to ethnically cleanse it of other groups living there, then wouldn’t that doctrine of ‘might makes right’ perfectly justify the Ottoman deportation of Jews from Tel Aviv and Jaffa that took place on this day 97 years ago? And if that violent act cannot be justified, then what could possibly justify Israel’s ethnic cleansing of Palestinians from the territories they won by armed force in 1948 and 1967…?

__________________________

“This Day in Jewish History”

Ottoman authority orders Jews to evacuate Tel Aviv

A total of 1,500 Jewish evacuees are thought to have died after heading north and being forced to lead a nomadic existence.

By David B. Green

Ha’aretz

April 6, 2014

April 6, 1917 was the day set by the Ottoman authorities then ruling Palestine for the evacuation of the civilian population of Tel Aviv and Jaffa. Although the Muslims who were expelled were permitted to return to their homes within days, the Jews were not able to come back to the city until after the British conquest of Palestine, later that same year.

Ottoman Turkey entered the Great War, on the side of the Central Powers, in November 1914. At the time, there were those among the Jewish residents of Palestine who had become Ottoman citizens, among them Meir Dizengoff, who at the time was head of the Tel Aviv planning commission, and would later be its first mayor.

Many of the new Jewish residents were recent arrivals from the Russian Empire, however, and their sympathies lay with Russia and its allies. They were a source of concern for the Turks, who feared they would become a fifth column when the front arrived in Palestine. Hence, as early as November 1914, Turkish authorities began going door-to-door in Tel Aviv and Jaffa, checking who did and didn’t have Ottoman citizenship. The following month, 750 in the latter group – Russian-born Jewish immigrants – were deported to Alexandria, Egypt.

By January 1917, British forces were poised to begin their invasion of southern Palestine from Sinai. On March 28, Ahmed Jemal Pasha, the Ottoman military governor of Syria (which included the Land of Israel), called together the leaders of the Jewish community in Tel Aviv and told them of his decision to evacuate them from the city. They were given a week to organize themselves and make arrangements for resettlement. Dizengoff, in his memoirs, recounted how Jemal explained that the move was being made for their own safety, and how he himself was dubious of that justification. There was apparently no resistance on the part of those being expelled.

April 6, Passover Eve, was the date by which the city’s estimated 10,000 civilian residents had to be gone. The first group went to Petah Tikva or Jerusalem. By the end of Pesach, a week later, the Turks ordered the evacuees to head further north. The remainder went on to Kfar Sava, Zichron Yaakov and Haifa, transported by wagon, and to Tiberias, which they arrived at by taking a train to Tzemah, at the southern end of Lake Kinneret. Some even ended up in Damascus.

Despite the assistance of local and American charities, and some cooperation from other Jewish communities in hosting the Jews of Tel Aviv, the deportees suffered high mortality rates. The poorest of them, who had no fixed place to resettle, found themselves forced into a nomadic existence. Many fell victim to typhus, or to hunger and the cold weather. A total of 1,500 are thought to have died, with many of them being buried in unmarked graves.

In an article in Haaretz Hebrew Edition in 2007, Nadav Shragai described historical research that uncovered the testimony of Ephraim Keter, who was a boy of 12 when his family was expelled from Tel Aviv. Both his parents died during the summer of 1917, and were buried in unmarked graves in Yavne’el. After the war’s end, he and his brother and other orphans among the evacuees were gathered in Sejera. Ephraim’s brother, Yehoshua Yona, contracted rubella and was taken to a hospital, where he died. Ephraim was never told where he was buried.

By December, 1917, the British had conquered Tel Aviv and Jaffa, and the city’s Jewish residents began making their way back to the city. The Turks only surrendered on October 31, 1918, with the war ending in Europe on November 11.